REVIEW ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS

Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Cancer

Yu Tian1, Noushin Nabavi2, Milad Ashrafizadeh3#

Received 2025 Aug 10

Accepted 2025 Oct 14

Epub ahead of print: December 2025

Published in issue 2026 Feb 15

Correspondence: Milad Ashrafizadeh - Email: dvm.milad1994@gmail.com

The author’s information is available at the end of the article

© 2026 The Author(s). Published by GCINC Press. Open Access licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. To view a copy: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a reversible process that enables carcinoma cells to become invasive and therapy-resistant, thereby affecting clinical outcomes such as relapse and treatment failure. In tumors, EMT is triggered by pathways such as TGF-β, Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, MAPK, hypoxia, and inflammatory cytokines. These activate EMT-inducing transcription factors, including Snail, Slug, Twist, and ZEB1/2. Noncoding RNAs, like the ZEB-miR-200 axis, also play roles. These changes create intermediate epithelial-mesenchymal states linked to collective migration, stemness, tumor recurrence, and therapy resistance. EMT also promotes immune evasion. Myeloid and stromal cells, especially tumor-associated macrophages and MDSCs, promote EMT and suppress antitumor immunity. EMT reduces antigen presentation, increases immune checkpoints such as PD-L1, and alters chemokines to attract immunosuppressive T cells, helping tumors evade detection. EMT contributes to multidrug resistance by altering cell adhesion and motility and by activating kinases such as STAT3, AXL, and EGFR/ERK. Targeting or reversing EMT can increase tumor sensitivity to treatment and improve outcomes. Combinations of EMT inhibitors (e.g., TGF-β and PI3K inhibitors), epigenetic therapies, and RNA-based reprogramming are being evaluated. New multi-omics and liquid biopsy technologies enable real-time monitoring of EMT status to support more personalized care. Recognizing EMT as a key driver of tumor progression creates new opportunities for targeted treatment.

Keywords: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), Cancer metastasis, Drug resistance, Signaling pathways, Tumor microenvironment, Immune evasion, Cancer stemness, Immune checkpoints

1. Introduction

In 2025, the United States is projected to record over 2 million new cancer diagnoses and more than 618,000 cancer-related deaths. Although overall cancer mortality has progressively declined, resulting in an estimated 4.5 million fewer deaths since 1991 due to reduced smoking, earlier detection, and advancements in treatment, significant disparities persist. Notably, Native American and Black populations continue to experience higher mortality rates across several cancer types compared to White populations. Concurrently, while cancer incidence is decreasing among men, it is increasing among women, especially in younger and middle-aged groups. For example, the incidence among women under 50 is now 82% higher than among men, and lung cancer incidence among women under 65 has surpassed that of men. Together, these trends underscore the need for a greater emphasis on prevention, early detection, and equitable healthcare, particularly among underserved populations (1).

The population of cancer survivors in the United States is growing, fueled by an aging population, overall population increase, and advances in early detection and treatment. As of January 1, 2025, there were 18.6 million survivors, with projections exceeding 22 million by 2035. For men, the most common cancers are prostate, melanoma, and colorectal, while for women, breast, uterine, and thyroid cancers are most frequent. More than half of survivors were diagnosed within the past decade, and over 80% are age 60 or older. Despite these advances, significant racial disparities persist. For example, Black patients with early-stage lung or rectal cancer are less likely to undergo surgery compared with White patients. Addressing these inequities with comprehensive, multi-level strategies is therefore essential to ensure quality treatment and survivorship support for all (2).

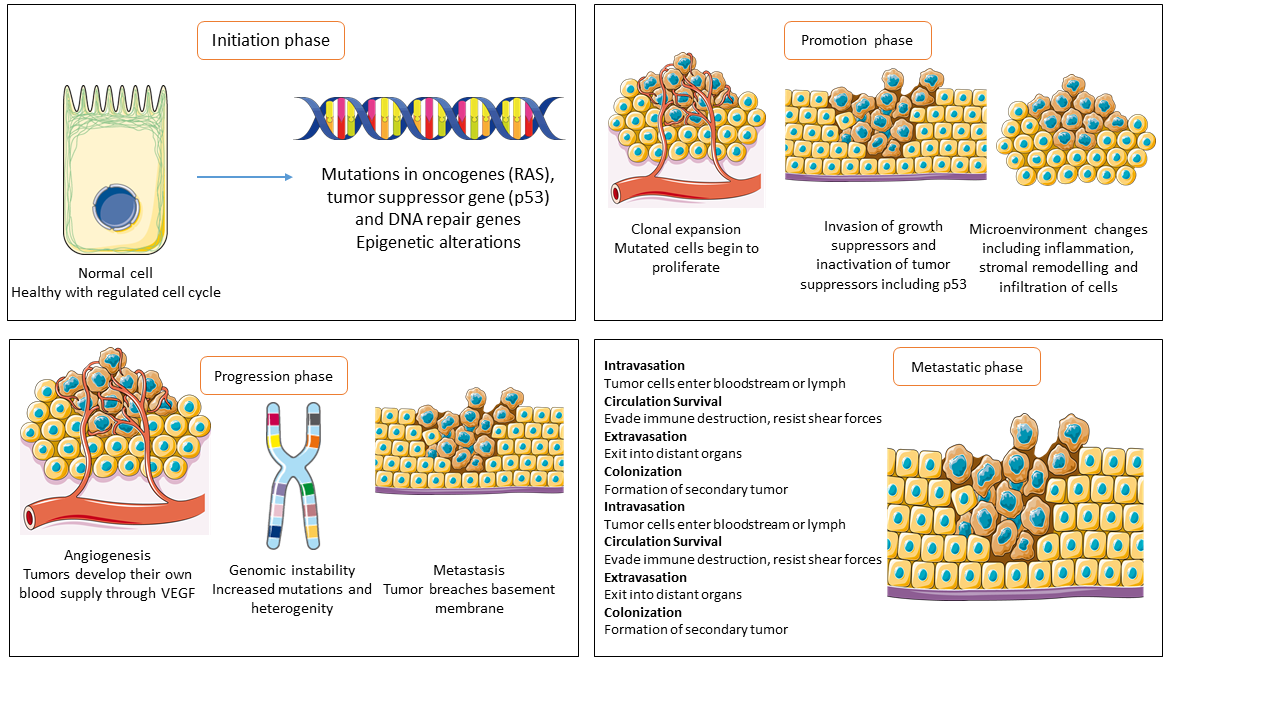

Metastasis remains a significant challenge in oncology, as it involves a small subset of tumor cells detaching from the primary site, surviving in circulation, and colonizing distant organs to form secondary tumors. Crucially, metastasis is responsible for over 90% of cancer-related deaths, with its invasive and therapy-resistant nature making treatment particularly difficult. Notably, immunotherapy has improved outcomes for some cancers, such as melanoma and lung cancer, yet most metastatic tumors continue to carry poor prognoses. Therefore, understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms that drive metastasis is essential. One key process is epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which enables epithelial tumor cells to acquire mesenchymal-like properties. This transition increases their motility, invasiveness, and resistance to therapy, changes that depend on complex networks of signaling pathways, transcription factors, epigenetic regulators, and noncoding RNAs. Furthermore, EMT contributes to immune evasion and chemoresistance (Figure 1).

Given the profound significance of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in driving cancer progression, this review comprehensively synthesizes current knowledge regarding the roles of EMT in cancer. Emphasis is placed on its diverse regulatory mechanisms, metastasis, and therapy resistance across multiple tumor types. In addition, the review explores emerging and established strategies to target EMT-related processes and discusses how such interventions may improve clinical outcomes by reducing recurrence and enhancing treatment sensitivity. By combining insights from molecular biology, immunology, and oncology, this review highlights EMT as both a cellular program and a key driver within the tumor microenvironment. Elucidating the complex processes underlying EMT is expected to provide novel perspectives on tumor progression and to support the development of more effective, personalized, and durable therapeutic interventions that can reshape future cancer care.

Figure 1: Cancer develops through several phases, each shaped by molecular and cellular events. The initiation phase involves epigenetic changes and oncogene mutations, leading to neoplastic transformation. During promotion, altered cells expand, evade growth suppression, and interact with the microenvironment to aid tumor development. Tumors gain angiogenesis, invasiveness, and genomic instability as they progress. Metastatic cancer cells spread to distant organs, causing most cancer deaths. Understanding molecular circuits, particularly in metastasis, is essential for preventing spread and improving outcomes.

2. EMT mechanism: basics and principles

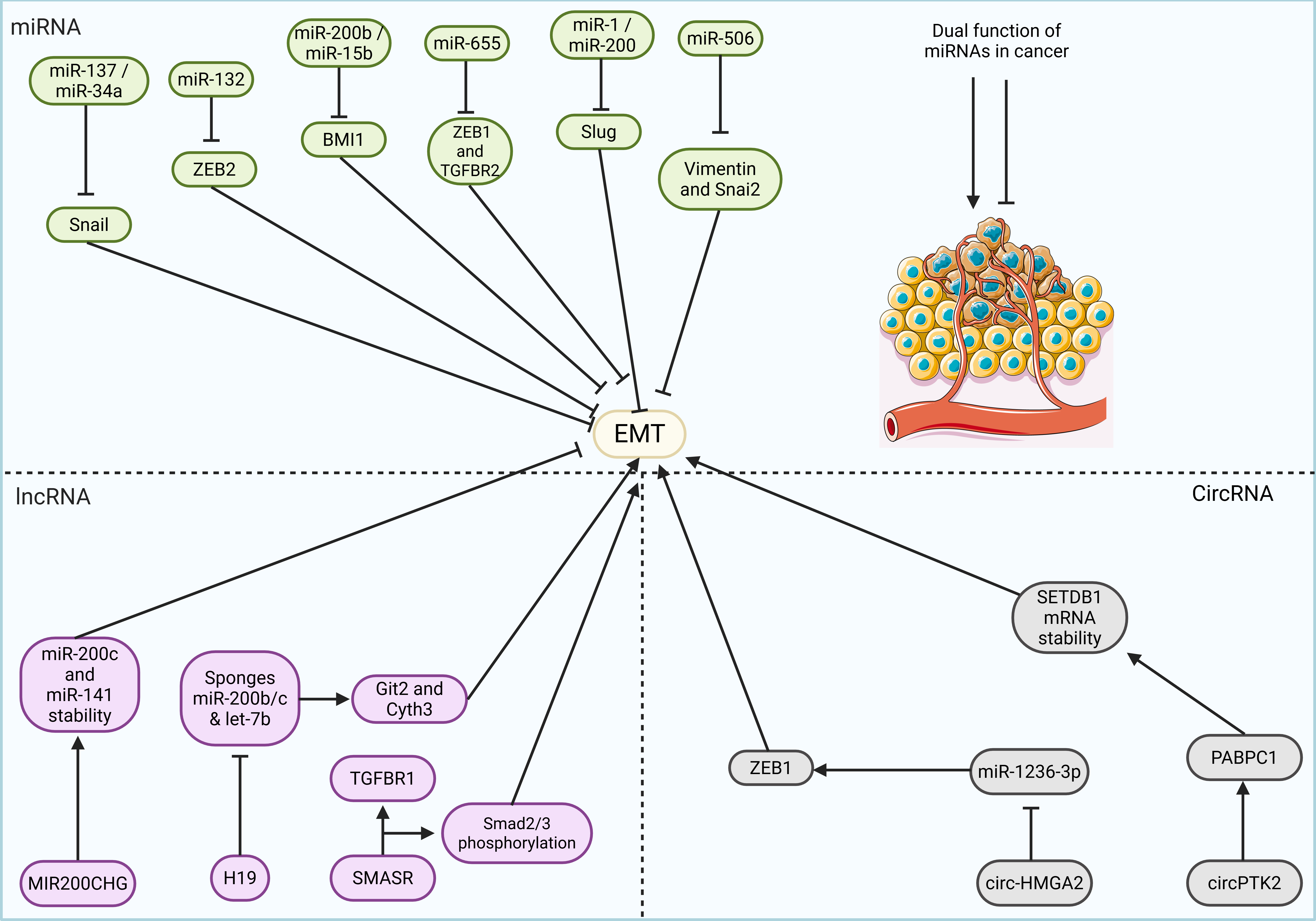

EMT involves molecular signals within the tumor microenvironment that affect tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis. Enzymes such as MMPs, regulated by TGF-β/Smad signaling, and developmental EMT programs are key to processes such as intravasation, extravasation, and colonization. EMTs are classified into three types: type I (embryogenesis), type II (wound healing/tissue repair), and type III (tumor progression/spread). These subtypes are influenced by the tumor microenvironment, stromal-epithelial interactions, and immune responses, all of which affect therapy response. Stromal fibroblast activation disrupts epithelia and fosters invasion. In development, EMT shapes germ layers. In cancer, similar processes raise vimentin/N-cadherin levels and lower E-cadherin levels, markers of aggressiveness. Wnt and TGF-β/Nodal/Vg1 pathways regulate EMT transcription factors, including Snail, EOMES, and Mesp1/2. Snail reduces E-cadherin and integrins, thereby enabling progression; some effects are reversible. Changes in EMT-related miRNAs, including decreased miR-200 levels, enhance tumor plasticity and metastasis, thereby affecting prognosis. Inhibiting TGF-β (e.g., SB-431542) can block activin- and miR-200-mediated changes, suggesting these pathways as potential therapeutic targets (6).

In normal tissues, EMT is controlled by networks that regulate EMT transcription factors (EMT-TFs) at both transcriptional and post-translational levels (7). Controls include alternative splicing, non-coding RNAs, epigenetic changes, and protein stability (8-14). EMT-TFs activate mesenchymal genes and affect other cellular processes by regulating gene expression (11, 15, 16). EMT promotes tumor growth and spread, and affects tumor initiation and therapeutic responses (16,17). In cancer, EMT is dynamic and reversible, marked by shifting cellular states that mimic embryonic development. EMT and its reverse, mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), cycle in early development and morphogenesis (7,15,16,18).

EMT refers to the process by which stationary epithelial cells transition into a motile mesenchymal phenotype (19). This phenomenon was first identified in early embryonic development (20), where it plays a crucial role in processes such as gastrulation, neural crest formation, and cardiac development (15, 16). EMT also contributes to essential physiological processes, including wound healing (21) and tissue homeostasis (22). Importantly, abnormal reactivation of EMT is a key driver in the development of pathological conditions, including organ fibrosis and the progression of cancer to metastasis (19). All cells in the human body originate from a single progenitor, with distinct phenotypes arising through the selective activation of specific transcriptomes that drive functional specialization. During embryonic development, epithelial cells exhibit remarkable plasticity, allowing them to switch between epithelial and mesenchymal states via the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and its reverse, the mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) (23). After organogenesis is complete, epithelial cells adopt specialized functions (24,25).

For many years, it was believed that epithelial cells must undergo terminal differentiation to perform their specialized functions and that this state was irreversible. This view has been overturned by evidence showing that even terminally differentiated epithelial cells can undergo phenotypic changes in response to repair-associated or pathological stress. One of the core mechanisms driving cellular diversity during both development and adulthood is EMT. As highlighted by Robert Weinberg and colleagues (26), EMT plays central roles across various biological contexts, promoting cell dispersion during embryogenesis, driving the generation of mesenchymal cells or fibroblasts in response to tissue injury, and enhancing the invasive and metastatic potential of epithelial cancer cells. Beyond its developmental functions, EMT is also linked to evolutionary processes that enabled the emergence of complex multicellular organisms. In adult tissues, EMT is reactivated during wound healing, tissue regeneration, and the progression of fibrotic diseases, thereby facilitating the generation of mesenchymal cells critical for tissue remodeling. In cancer, genetic alterations in epithelial cells create selective pressures that support both local invasion and systemic spread, processes greatly amplified by EMT, which endows tumor cells with migratory and invasive capacities (23).

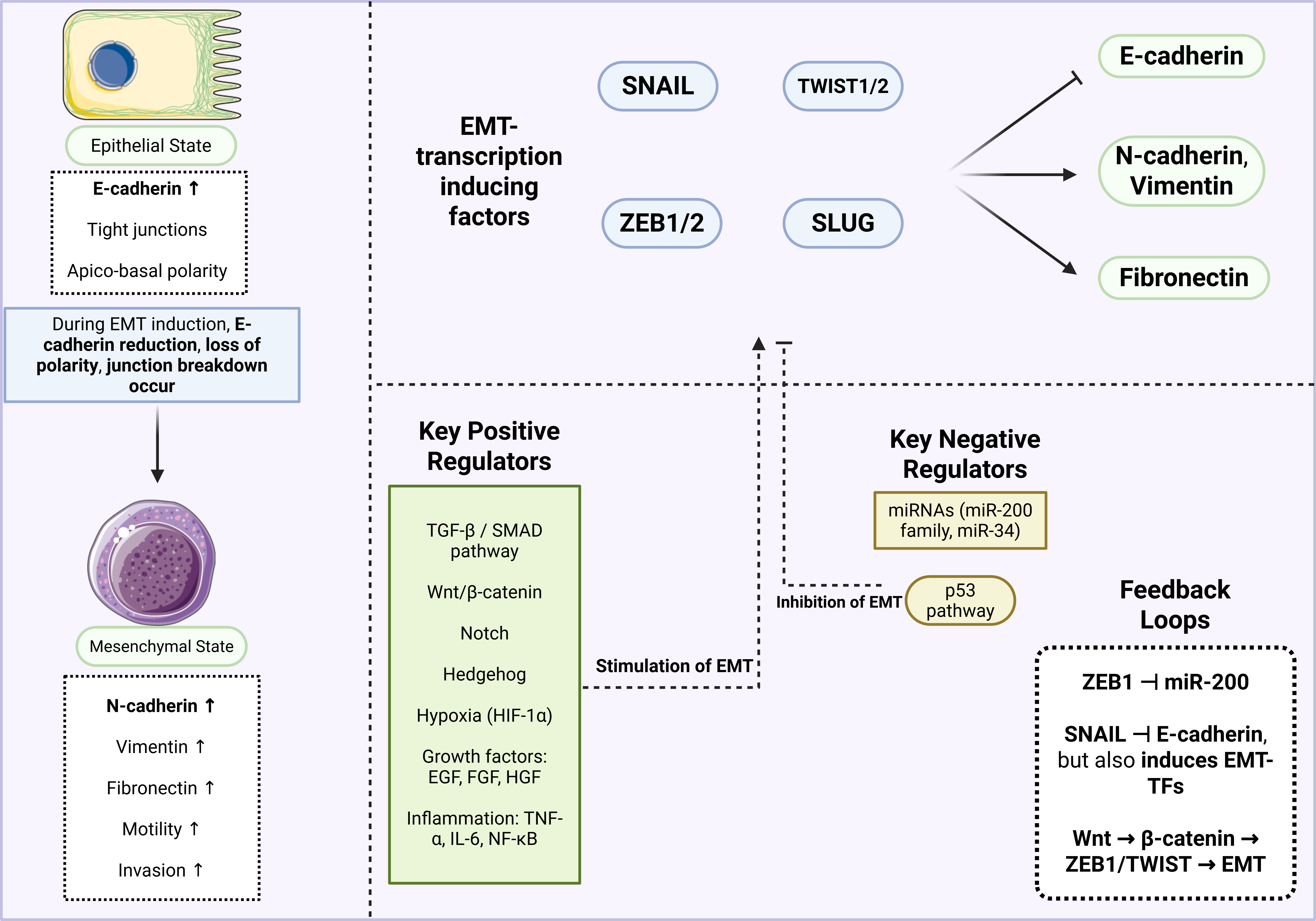

EMT is regulated by several key signaling pathways, most notably TGF-β, Notch, and Wnt (27). The tumor microenvironment (TME) further shapes these pathways through external influences, including hypoxia and alterations in microRNA (miRNA) expression (28,29). Despite their differences, these signaling pathways converge on a common set of transcription factors, Snail (SNAI), Zeb, and Twist, that are well known for driving EMT when aberrantly expressed in cancers. Through both canonical and non-canonical routes, TGF-β signaling regulates the expression of transcription factors, including Snail, Zeb, Twist, and Six1 (29). Similarly, Notch signaling activates NF-κB, which in turn promotes the transcription of SNAI1, SNAI2 (also known as Slug), Twist, and Zeb1/2, while also enhancing cytokine secretion and supporting cell survival. The Wnt pathway, frequently dysregulated in cancers, upregulates SNAI1 expression and represses E-cadherin by activating β-catenin. Additionally, environmental stresses, such as hypoxia, disrupt mitochondrial function, triggering HIF-1 activation and elevating Zeb1 expression (27). Figure 2 provides an overview of the EMT mechanism and its associated factors. In this process, epithelial cells transition into mesenchymal cells, characterized by the upregulation of N-cadherin, vimentin, and fibronectin, along with increased cell motility, accompanied by the downregulation of E-cadherin. EMT-inducing transcription factors, including SNAIL, SLUG, TWIST1/2, and ZEB1/2, play a central role in driving this transition. Both positive and negative regulators, such as TGF-β, Wnt/β-catenin, miRNAs, Hedgehog, Notch, and hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), further modulate the process. Additionally, feedback loops, such as the interaction between ZEB1 and the miR-200 family, contribute to the fine regulation of EMT.

Figure 2: An overview of the EMT mechanism. In the epithelial state, cells exhibit high E-cadherin expression, tight junctions, and apico-basal polarity. During EMT, however, cells transition to a mesenchymal state characterized by upregulation of N-cadherin, vimentin, and fibronectin, thereby increasing motility and invasiveness. Key transcription factors, including SNAIL, SLUG, TWIST, and ZEB, drive this transition, while both positive and negative regulators modulate the process. Given EMT’s critical role in cancer progression, inhibiting it offers promising opportunities for novel therapeutic strategies.

During EMT, cells activate multiple interconnected signaling pathways that form a complex regulatory network of genes, growth factors, and cytokines. Although most illustrations capture only part of this crosstalk, it highlights the intricate control of EMT. A hallmark of EMT is the active reorganization of the cytoskeleton, a process critical for enabling cell migration and motility during metastasis. TGF-β is a key initiator of EMT, acting through both canonical and non-canonical signaling pathways. In the canonical pathway, TGF-β activates SMAD protein complexes that control transcription factors involved in apoptosis and cell adhesion. Through the non-canonical pathway, TGF-β engages the PI3K/Akt signaling cascade, promoting protein synthesis, cell proliferation, and resistance to anoikis. It also activates Rho GTPases and JNK signaling, promoting junction disassembly and cytoskeletal reorganization, key steps in invasion and motility. The MAPK/ERK pathway may be triggered either by TGF-β signaling or through integrin-mediated cell-cell interactions, leading to PI3K activation and the enhancement of mesenchymal characteristics. Similarly, receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) activated by growth factors stimulate MAPK/ERK signaling, thereby enhancing mesenchymal characteristics. Additional pathways, including Wnt, Hippo, and Notch, further contribute to EMT by downregulating adhesion molecules, promoting cell detachment, and inhibiting anoikis, thereby amplifying the migratory and invasive potential of cells undergoing EMT (30).

In metastatic cells undergoing EMT, transcription factors such as Snail, Twist, and Zeb are upregulated (31). Snail is strongly regulated by TGF-β signaling, which downregulates cadherin-16 and HNF-1β, key components of the epithelial phenotype, thereby driving EMT (32). Cancer cells must overcome the pro-apoptotic effects of TGF-β to survive, and EMT-associated transcription factors play a central role in this adaptation. Snail, for example, enhances cancer cell survival by upregulating anti-apoptotic proteins such as Akt and Bcl-xL, effectively protecting cells from TGF-β-induced apoptosis (33). Interestingly, while promoting survival, Snail also suppresses cell cycle progression by downregulating Cyclin D2, consistent with the reduced proliferation observed during EMT-associated differentiation (34).

Additionally, the insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-1R) contributes to EMT induction. In mammary epithelial cells, IGFR activates NF-κB and Snail, facilitating the transition to a mesenchymal phenotype. In prostate cancer, IGFR signaling has been linked to increased Zeb expression and activation of latent TGF-β1, further reinforcing EMT programs and promoting tumor progression (31,35,36).

3. EMT in cancer drug resistance

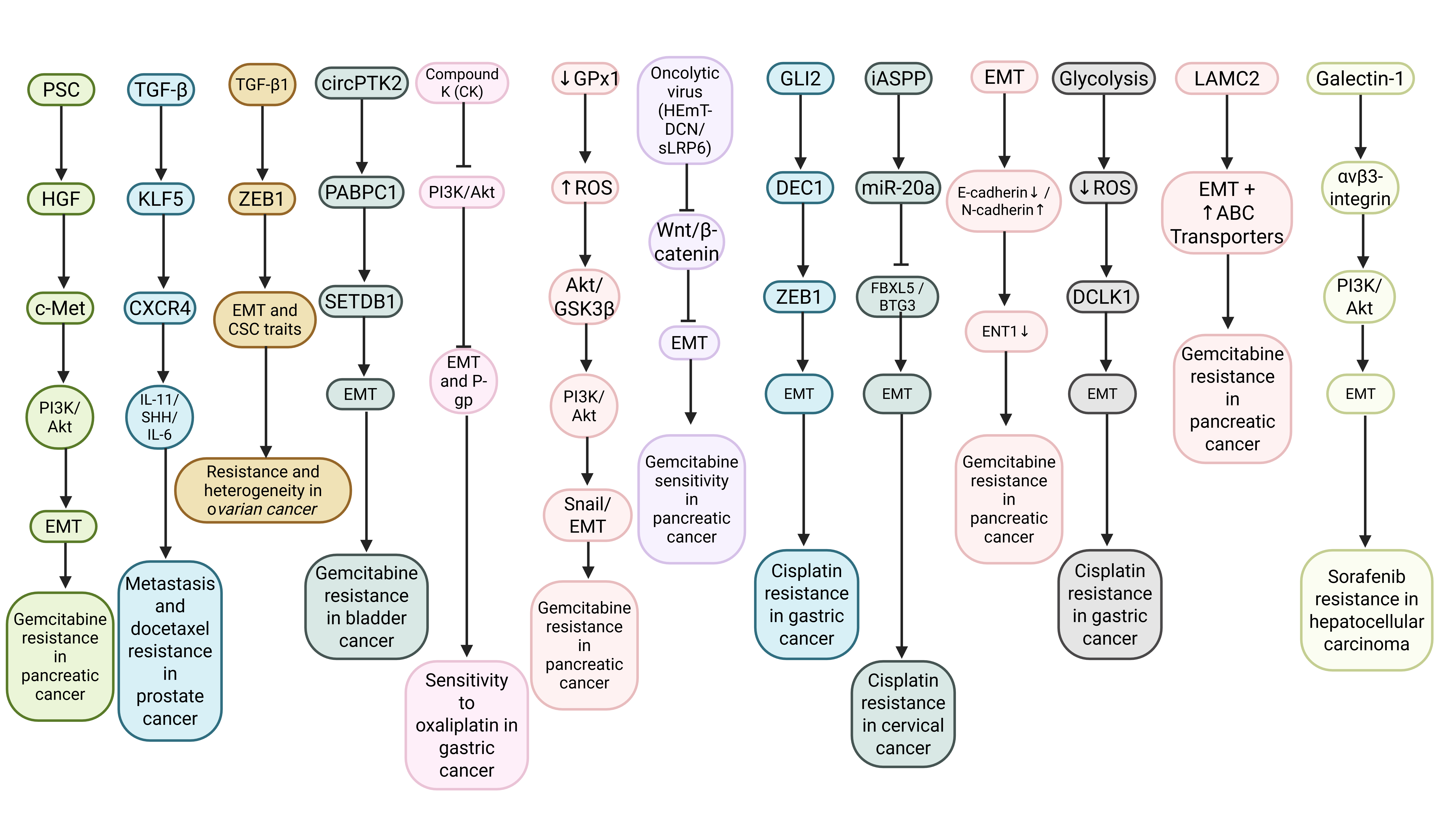

Chemoresistance is a significant challenge in the treatment of many cancers, with increasing evidence underscoring the critical roles of the TME, EMT, and key signaling pathways in driving drug resistance and tumor progression. In pancreatic cancer (PC), pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) secrete hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), which activates the c-Met/PI3K/Akt pathway in PC cells (PCCs), promoting EMT and inhibiting apoptosis, thereby contributing to gemcitabine resistance (37). In PCa bone metastases, bone-derived TGF-β induces the acetylation of KLF5, enhancing resistance to docetaxel and promoting metastasis through CXCR4-mediated IL-11 and SHH/IL-6 paracrine signaling. This process can be therapeutically reversed by targeting CXCR4 (38). In ovarian cancer, TGFβ1 enhances cancer stem cell (CSC)-like properties and drives EMT through both Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways, with ZEB1 as a key transcription factor, ultimately leading to increased resistance and tumor heterogeneity (39). In bladder cancer, CircPTK2 interacts with PABPC1 to stabilize SETDB1 mRNA, thereby promoting EMT, enhancing metastasis, and driving gemcitabine resistance through the circPTK2/PABPC1/SETDB1 axis (40). In gastric cancer, the ginsenoside derivative Compound K overcomes oxaliplatin resistance by suppressing the PI3K/Akt pathway, reversing EMT, and decreasing drug efflux through downregulation of P-gp, thereby demonstrating potent antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo (41). In gastric cancer, the ginsenoside derivative Compound K reduces oxaliplatin resistance by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt pathway, reversing EMT, and lowering drug efflux via downregulation of P-gp, demonstrating strong anti-tumor effects in both in vitro and in vivo models. The unfavorable prognosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is partly attributed to its resistance to chemotherapy. Glutathione peroxidase-1 (GPx1), a key antioxidant enzyme implicated in several cancers, remains unclear in PDAC. Tissue microarray analyses revealed that higher GPx1 expression was associated with shorter overall survival in patients with PDAC. GPx1 inhibition promoted a mesenchymal phenotype and enhanced gemcitabine resistance in both in vitro and in vivo models. RNA sequencing demonstrated that this effect was mediated, in part, through the activation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced Akt/glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β)/Snail signaling. Furthermore, low GPx1 expression was associated with worse outcomes in PDAC patients treated with GEM-based adjuvant chemotherapy, which was not observed in those receiving fluoropyrimidine-based regimens (42).

Prostate cancer is an aggressive malignancy characterized by extensive extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition and a pronounced EMT phenotype, both of which contribute to chemoresistance in desmoplastic tumors. To overcome these barriers, an oncolytic adenovirus co-expressing decorin and a soluble Wnt decoy receptor (HEmT-DCN/sLRP6) was evaluated in an orthotopic pancreatic xenograft model using Mia PaCa-2 cells implanted in athymic nude mice. Systemic administration of HEmT-DCN/sLRP6 elicited robust anticancer and antimetastatic effects. Histological analyses revealed marked ECM degradation, enhanced apoptosis, increased viral dissemination within the tumor, and effective inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Treatment with HEmT-DCN/sLRP6 suppressed EMT, reduced tumor cell proliferation, and significantly inhibited PC metastasis. Additionally, HEmT-DCN/sLRP6 increased gemcitabine sensitivity in pancreatic tumor xenografts and patient-derived tumor spheroids by facilitating greater drug penetration and distribution (43).

Chemoresistance remains a significant obstacle in cancer therapy, frequently driven by EMT, dysregulated signaling pathways, and CSC properties across multiple tumor types. In gastric cancer, the transcription factor GLI2, an essential mediator of the Hedgehog pathway, is upregulated in EMT-type GC and contributes to cisplatin resistance by promoting EMT through a novel GLI2/DEC1/ZEB1 axis (44). In cervical cancer, iASPP drives EMT and cisplatin resistance by upregulating miR-20a in a p53-dependent manner. This, in turn, suppresses the tumor suppressors FBXL5 and BTG3, resulting in increased cell invasion and a poor prognosis (45).In PC, EMT drives gemcitabine resistance through multiple mechanisms: cadherin switching from E-cadherin to N-cadherin reduces ENT1 expression and drug uptake, whereas EpCAM counteracts EMT and restores chemosensitivity (46).In gemcitabine-resistant PCCs, EMT and CSC phenotypes are sustained by glycolysis, which maintains low ROS levels and promotes DCLK1 production; inhibiting glycolysis or increasing ROS disrupts this resistance (47). Another study highlights the role of LAMC2, which is linked to poor prognosis in PDAC and promotes gemcitabine resistance by driving EMT and regulating ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters (48).

These results underscore the key role of EMT-related pathways, such as GLI2, iASPP/miR-20a, cadherin switching, DCLK1, and LAMC2, in promoting chemoresistance, making them promising targets for therapies to overcome drug resistance in gastrointestinal and gynecological cancers. Galectin-1 (Gal-1) also emerges as a key mediator of tumor progression and chemoresistance; however, its roles in EMT and sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remain uncertain. Recent evidence shows that elevated Gal-1 expression accelerates HCC development and reduces sorafenib sensitivity through αvβ3-integrin-mediated activation of the AKT pathway. Additionally, Gal-1 promotes EMT in HCC cells through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Clinically, high Gal-1 levels are associated with poorer survival and reduced sorafenib efficacy in patients with HCC, suggesting that Gal-1 may be a therapeutic target and a prognostic biomarker for predicting sorafenib response in HCC (49).

EMT has emerged as a key mechanism driving chemoresistance in multiple cancers, including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), colorectal cancer (CRC), and non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). In HNSCC, resistance to the EGFR inhibitor gefitinib is associated with EMT, exemplified by the UMSCC81B cell line variant (81B-Fb), which exhibits fibroblast-like morphology, reduced E-cadherin expression, and elevated vimentin and Snail levels (50). The EMT phenotype is driven by EGFR downregulation, facilitated by enhanced ubiquitination and activation of the Akt/GSK-3β/Snail signaling pathway. This effect can be partially reversed by the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 or by EGFR overexpression, indicating a pathway-specific mechanism underlying gefitinib resistance. In the context of MEK1/2 inhibitor (MEKi) resistance, amplification of oncogenic BRAFV600E or KRASG13D restores ERK1/2 signaling; however, only BRAFV600E-mediated resistance is reversible upon drug withdrawal (51). Reversibility depends on p57KIP2 activation, which induces G1 arrest and senescence, ultimately leading to loss of BRAFV600E amplification and renewed sensitivity to MEKi (Figure 3).

In contrast, KRASG13D amplification sustains ERK1/2 activation, driving a ZEB1-dependent EMT and persistent chemoresistance, rendering drug therapies ineffective. In CRC, high expression of the EMT-inducing transcription factor ZEB2 is associated with a poor prognosis and resistance to adjuvant FOLFOX therapy. ZEB2 fosters chemoresistance by upregulating the nucleotide excision repair pathway, particularly through ERCC1, thereby enhancing tumor survival against oxaliplatin. Consistently, tumors overexpressing ERCC1 demonstrated oxaliplatin resistance in vivo, highlighting the ZEB2-ERCC1 axis as a critical contributor to treatment failure and disease recurrence (52). In NMIBC, CXCL5 overexpression has been shown to drive mitomycin C resistance by inducing EMT and activating the NF-κB pathway (53). Exogenous CXCL5 reduced drug sensitivity in parental cells, whereas its knockdown restored responsiveness and suppressed EMT/NF-κB signaling. Collectively, these observations highlight the crucial role of EMT and its regulatory networks in driving chemoresistance across multiple cancer types by modulating growth factor receptors, transcriptional reprogramming, and cytokine signaling, underscoring the importance of targeting EMT-related pathways to overcome therapeutic resistance (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The EMT mechanism in cancer drug resistance. The figure illustrates key interactions among TME components, oncogenic signaling pathways (PI3K/Akt, Wnt/β-catenin), transcription factors (ZEB1, Snail, DEC1), metabolic reprogramming, and drug transport modulation. Upstream stimuli, including growth factors, cytokines, non-coding RNAs, and ECM remodeling, converge on EMT and CSC-like phenotypes, ultimately promoting reduced drug uptake, enhanced survival signaling, and increased metastatic potential. Inhibitory arrows depict therapeutic interventions targeting these pathways to restore chemosensitivity.

Table 1 describes how the acquisition of chemoresistance in cancer is closely linked to EMT induction, characterized by the loss of epithelial markers, upregulation of mesenchymal markers, and activation of EMT-associated transcription factors, including Snail, Slug, Twist, and the ZEB family. This transition frequently engages signaling pathways including STAT3, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, MAPK, ATM/JAK/STAT, and EGFR-driven cascades, which collectively enhance migration, invasion, stemness, and survival under therapeutic stress. EMT regulators promote drug resistance by reprogramming tumor cells into mesenchymal phenotypes, thereby diminishing their sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents and increasing their metastatic potential. Conversely, inhibition or silencing of EMT drivers or their upstream regulators has been shown to reverse the mesenchymal state, restore epithelial traits, and re-sensitize cancer cells to therapy. These findings highlight EMT-associated signaling networks as central mediators of therapeutic resistance, underscoring their value as targets for improving treatment efficacy and clinical outcomes.

Table 1: Chemoresistance in cancer and relation to EMT induction.

| Cancer Type | Drug/Resist Context | EMT Markers/Features | Key EMT Regulator | Signaling Pathway | Functional Outcome | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric Cancer | Cisplatin resistance: eIF5A2 overexpression reduced sensitivity | ↓ E-cadherin, ↓ β-catenin, ↑ N-cadherin, ↑ Vimentin; EMT induction | Twist, eIF5A2 | EMT | eIF5A2 promotes EMT → decreased sensitivity to cisplatin; knockdown of eIF5A2 or Twist restores sensitivity | (56) |

| Ovarian Cancer | Cisplatin resistance in A2780cis cells | ↓ E-cadherin, ↑ vimentin, ↑ Snail, ↑ Slug; spindle morphology, pseudopodia formation, increased migration and invasion |

Snail, Slug, Twist2, ZEB2, ZEB1, Twist1 |

EMT | EMT promotes cisplatin resistance, invasion, and migration; knockdown of Snail/Slug reverses EMT and re-sensitizes cells to cisplatin | (57) |

| Lung Cancer | Acquired resistance to cisplatin in A549 cells | ↑ N-cadherin, ↓ E-cadherin in WT-CisR; STAT3 KO reverses EMT to epithelial phenotype | STAT3 |

STAT3 mTOR mTORC Akt) |

STAT3 promotes EMT and cisplatin resistance via mTOR activation; STAT3 knockout prevents resistance, reverses EMT, and sensitizes cells to cisplatin and rapamycin | (58) |

|

Stomach Adeno carcinoma |

Cisplatin resistance associated with high Rab31 expression | ↓ E-cadherin, ↑ Vimentin, ↑ MMP-2, ↑ MMP-9; increased migration, colony formation, and apoptosis resistance | Twist1, STAT3, MUC-1 | Rab31 → STAT3 → MUC-1 ↓ → Twist1 ↑ → EMT | Rab31 promotes EMT and cisplatin resistance via Twist1; knockdown restores drug sensitivity and reduces metastasis | (59) |

| NSCLC | Cisplatin resistance in A549 and H157 cells; upregulated ATM expression | ↓ E-cadherin, ↑ N-cadherin, ↑ Vimentin, ↑ Snail, ↑ Zeb1, ↑ Twist, ↑ VEGF; mesenchymal morphology; increased invasion & migration |

ATM, PD-L1, JAK1/2, STAT3 |

ATM → JAK1/2 → STAT3 → PD-L1 → EMT | ATM promotes EMT and metastasis, leading to cisplatin resistance; inhibition of ATM reverses EMT and reduces metastasis both in vitro and in vivo | (60) |

| TNBC | Cisplatin (CIS) resistance; tested with sulforaphane (SFN) combination therapy | ↑ E-cadherin, Claudin, ZO1; ↓ N-cadherin, Vimentin, β-catenin, MMP-2/9; ↓ EMT-TFs: Snail, Slug, ZEB1; shift from mesenchymal to epithelial |

Snail, Slug, ZEB1, SIRT1, SIRT7 |

TGF-β1 → SIRTs (SIRT1/2/3/5/7) → EMT; SFN + CIS inhibit SIRTs and reverse histone deacetylation at E-cadherin promoter | SFN + CIS synergistically inhibit growth, trigger S-phase arrest, curb migration, invasion, reverse EMT, suppress sirtuins, restore E-cadherin, and overcome cisplatin resistance/metastasis. | (61) |

| Ovarian Cancer | Cisplatin resistance mediated by STAT3 phosphorylation at Tyr705 | ↓ E-cadherin; ↑ Vimentin, ↑ Slug, ↑ Snail; enhanced migration, invasion, and mesenchymal morphology |

STAT3 (pY705), Slug, Snail |

STAT3 → PI3K/AKT/mTOR & MAPK → inhibition of ER stress-induced autophagy | STAT3 activation drives EMT, proliferation, migration, invasion, and cisplatin resistance; STAT3 inhibition or p53 activation reverses EMT and restores sensitivity. RAS cooperates with STAT3 in resistance and tumorigenesis. | (62) |

| HCC | Doxorubicin resistance: higher ARK5 expression correlates with lower drug sensitivity | ↓ E-cadherin; ↑ Vimentin under doxorubicin or hypoxia; reversed upon ARK5 knockdown | ARK5, TWIST | ARK5 → EMT (via TWIST); EMT likely mediates drug resistance | ARK5 knockdown increases doxorubicin sensitivity under normoxia/hypoxia and reverses EMT. TWIST knockdown blocks EMT and prevents ARK5-driven resistance. ARK5 induces resistance by promoting EMT, but not when EMT is already blocked. | (63) |

| TNBC | Doxorubicin resistance in MDA-MB-231cells through chronic exposure | ↓ E-cadherin; ↑ N-cadherin, β-catenin, ICAM-1; increased CD44 and OCT3/4; mesenchymal morphology | ↑ EGFR | EGFR → AKT/ERK signaling; EGFR downstream pathways promote EMT, CSC, drug resistance | DRM cells enhance proliferation, migration, invasion, adhesion, CSC expansion, EMT traits, and doxorubicin resistance. This resistance spreads to parental cells via autocrine signals, while EGFR‑AKT/ERK pathways maintain EMT and CSC features, driving resistance. | (64) |

4. Major molecular pathways regulating EMT in cancer

4.1 PI3K/Akt/mTOR and PTEN signaling pathway

EMT, a key mechanism in tumor invasion and metastasis, provides valuable insights for the development of novel cancer therapies. Sotetsuflavone, a natural compound derived from Cycas revoluta, has shown notable anticancer activity during the early stages of tumor progression. A study investigated the antimetastatic effects of sotetsuflavone in vitro, demonstrating that it suppresses metastasis and EMT in A549 non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells. The inhibitory effect was marked by increased E-cadherin expression and decreased levels of N-cadherin, vimentin, and Snail. Mechanistic analysis revealed that HIF-1α plays a central role in mediating sotetsuflavone's anti-metastatic activity. The compound modulated VEGF signaling by downregulating VEGF and upregulating angiostatin, while also reducing MMP-9 and MMP-13 expression. Furthermore, sotetsuflavone inhibited HIF-1α activity by suppressing the PI3K/AKT and TNF-α/NF-κB pathways (63).

EMT and angiogenesis are recognized as key mechanisms in cancer progression. Curcumin, known for its favorable safety profile, has been widely studied in both preclinical and clinical settings for cancer prevention. However, its role in regulating EMT and angiogenesis in lung cancer remains insufficiently understood. In this study, curcumin suppressed induced cell migration and EMT-related morphological changes in A549 and PC-9 lung cancer cells. Pretreatment with curcumin inhibited HGF-induced c-Met phosphorylation and downstream activation of Akt, mTOR, and S6 proteins, effects comparable to those of the c-Met inhibitor SU11274, the PI3K inhibitor LY294002, and the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin. Overexpression of c-Met further confirmed that curcumin blocks EMT in lung cancer cells by interfering with the c-Met/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Additionally, curcumin markedly suppressed PI3K/Akt/mTOR activity, induced apoptosis, and inhibited migration and tube formation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) stimulated by HGF. In a murine experimental model, curcumin reduced HGF-driven tumor growth, accompanied by increased E-cadherin expression and decreased levels of vimentin, CD34, and VEGF (64).

The intricate dynamics of cancer progression consistently highlight EMT as a central driver of tumor dissemination and poor prognosis across diverse malignancies. Among its regulators, the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway has emerged as a critical hub linking oncogenic proteins to cancer aggressiveness. In CRC, FAT4, a well-known tumor suppressor, was found to be downregulated in tumor tissues and shown to inhibit invasion, migration, and proliferation by enhancing autophagy and suppressing EMT through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and PI3K/AKT/GSK-3β pathways. In bladder cancer, TEAD4 was identified as an oncogene strongly associated with higher tumor grade and poorer survival; it promoted EMT and metastasis in both in vitro and in vivo models by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway, whereas pharmacological inhibition of this pathway reduced TEAD4-driven malignancy. Similarly, transforming acidic coiled-coil protein 3 (TACC3) has been shown to induce EMT and enhance transformation, proliferation, and invasion across multiple cancers by activating both the PI3K/AKT and ERK pathways, suggesting it is a viable therapeutic target. In thyroid cancer, the hematopoietic PBX-interacting protein (HPIP) functions as an oncogene, and its silencing effectively suppresses proliferation, migration, and EMT by inhibiting PI3K/AKT signaling. Together, these findings underscore the diverse yet interconnected roles of FAT4, TEAD4, TACC3, and HPIP in regulating EMT and metastasis via the PI3K/AKT axis, positioning them as promising therapeutic targets to halt tumor progression and improve patient outcomes (65-68).

The Williams syndrome transcription factor (WSTF), encoded by the BAZ1B gene, was initially identified as a hemizygously deleted gene in individuals with Williams syndrome. WSTF functions in transcription, replication, chromatin remodeling, and the DNA damage response, and acts as a tyrosine protein kinase. In lung cancer cell lines A549 and H1299, WSTF overexpression was shown to enhance proliferation, colony formation, migration, and invasion. In vivo studies using mouse xenograft models further confirmed that elevated WSTF expression drives tumor growth and invasiveness. Transcriptomic profiling, validated by qRT-PCR, revealed that WSTF overexpression significantly upregulates EMT markers, including fibronectin (FN1), and EMT-inducing genes, including Fos and CEACAM6. These molecular changes were characterized by reduced E-cadherin and increased N-cadherin and FN1 expression at both mRNA and protein levels, along with morphological features consistent with EMT. Mechanistically, WSTF was found to activate PI3K/Akt and IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathways. Pharmacological inhibition with the PI3K inhibitor ZSTK474 or the STAT3 inhibitor niclosamide reduced WSTF-induced proliferation, migration, and invasion, while lowering the levels of phosphorylated Akt, phosphorylated STAT3, and IL-6. Importantly, these inhibitors also restored epithelial markers and suppressed EMT-related transcription factors, including Snail, Slug, Twist, and CEACAM6, in WSTF-overexpressing A549 cells (69).

The ubiquitin-binding enzyme E2T (UBE2T), a member of the E2 ubiquitin-proteasome family, has been implicated in carcinogenesis across multiple malignancies, but its role in ovarian cancer has only recently been clarified. Emerging evidence shows that UBE2T is markedly overexpressed in ovarian cancer tissues, particularly in cases with BRCA mutations, and this elevated expression strongly correlates with poor patient prognosis. Immunohistochemical analysis confirmed UBE2T upregulation, representing the first report linking its expression to BRCA-mutated ovarian cancer. Functional studies demonstrated that silencing UBE2T significantly reduced ovarian cancer cell proliferation and invasion, while suppressing EMT and downregulating PI3K-AKT signaling. Conversely, treatment with the mTOR activator MHY1485 reactivated PI3K-AKT signaling and largely restored the proliferative and invasive capacity of UBE2T-deficient cells. In vivo tumorigenesis experiments in nude mice further validated that UBE2T knockdown inhibited tumor growth and EMT in tumor tissues. Collectively, these findings suggest that UBE2T acts as an oncogenic driver in ovarian cancer by regulating EMT through the PI3K-AKT pathway, potentially in cooperation with BRCA mutations. Thus, UBE2T holds promise as a novel biomarker for early diagnosis, prognosis, and targeted therapy in ovarian cancer, and its inhibition may represent a viable therapeutic strategy (70).

KIAA1199 is frequently upregulated in various cancers, including NSCLC, where its expression is associated with aggressive tumor behavior and poor patient survival. Analyses of preserved clinical specimens revealed significantly higher KIAA1199 mRNA and protein levels in NSCLC tissues than in adjacent normal tissues, and higher expression was an independent predictor of overall survival. Functional studies in NSCLC cell lines demonstrated that KIAA1199 regulates EMT by altering the expression of EMT markers, EMT-inducing transcription factors, and associated signaling molecules. Gene silencing or overexpression of KIAA1199 correspondingly modulated EMT pathway activity, highlighting its regulatory role in this process. In a mouse xenograft model, KIAA1199 knockdown significantly suppressed tumor growth and enhanced treatment response. Collectively, these findings indicate that KIAA1199 acts as a prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target in NSCLC by modulating EMT signaling (71).

EMT plays a central role in promoting tumor progression across various cancers, including colorectal and lung cancer, and is closely controlled by the tumor suppressor PTEN. In CRC cells, PTEN loss induces EMT through Akt activation and alters chromatin accessibility by phosphorylating EZH2 at Ser21. This modification converts EZH2 from a repressor to an activator, disrupting its association with the PRC2 component SUZ12 and reducing H3K27me3 levels. The resulting epigenetic reprogramming activates transcription factors such as AP1, thereby promoting EMT (72). In colon cancer cells, treatment with 2′-benzoyloxycinnamaldehyde (BCA) suppresses EMT and invasion by upregulating EGR1, which in turn enhances PTEN expression (73). Silencing EGR1 or PTEN diminishes the inhibitory effects of BCA on EMT markers, including Snail and β-catenin. In lung cancer, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated PTEN deletion enhances proliferation, migration, invasion, and metastasis in vivo, accompanied by increased phosphorylation of Akt and GSK-3β, as well as nuclear translocation of β-catenin, Snail, and Slug (74). PTEN-deficient cells also display morphological changes characteristic of EMT, including reduced cell-cell adhesion and increased pseudopodia formation. These findings highlight the crucial role of PTEN in preserving epithelial integrity and inhibiting EMT across various cancers, primarily by regulating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and modulating β-catenin localization. EMT, a critical driver of cancer progression and metastasis, is controlled by multiple molecular factors, with phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) acting as a central modulator in many tumor types. In gastric cancer, the oncogenic enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (Ezh2) is overexpressed. It promotes tumor growth, EMT, and CSC-like traits by suppressing PTEN and activating the Akt pathway, with the PTEN/Akt axis mediating these effects (75). In endometrial carcinoma, PTEN overexpression induces EMT and CSC traits by activating nuclear β-catenin and Slug, while concurrently reducing proliferation and promoting apoptosis, particularly in ERα/EBP50-deficient contexts (76). PRL-3, a metastasis-associated phosphatase, promotes EMT by activating the PI3K/Akt pathway and suppressing PTEN expression, thereby reducing epithelial marker expression, reorganizing the actin cytoskeleton, and enhancing cell motility; these effects depend on its phosphatase activity (77). In tongue squamous cell carcinoma (TSCC), PTEN overexpression suppresses proliferation, invasion, and EMT by downregulating Hedgehog signaling, thereby reinforcing its tumor-suppressive role (78). Across these studies, PTEN emerges as a key suppressor of EMT and metastasis, primarily by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt pathway and its downstream transcription factors, such as Snail and Slug. However, in specific contexts, such as endometrial carcinoma, PTEN can paradoxically promote EMT and CSC traits via alternative signaling routes, underscoring its complex, context-dependent role. PTEN and its regulatory network, including modulators such as Ezh2, PRL-3, and EGR1, therefore represent compelling therapeutic targets for blocking EMT and limiting cancer progression. Chronic inflammation is a well-established contributor to cancer progression, with cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) playing a significant role in enhancing tumor invasiveness. In human colon cancer cell lines HCT116 and SW480, siRNA-mediated knockdown of the tumor suppressor PTEN significantly increased cell invasion and motility, as demonstrated in Boyden chamber and scratch assays. When PTEN-deficient cells were exposed to TNF-α, their invasive and migratory capacities were further enhanced, suggesting a synergistic effect between PTEN loss and TNF-α-mediated inflammatory signaling. Mechanistically, PTEN silencing led to nuclear accumulation of β-catenin and upregulation of its downstream targets, c-Myc and cyclin D1, both of which are implicated in tumor development. These findings align with clinical observations linking PTEN deficiency to advanced stages of CRC and suggest that genetic alterations within tumor cells, combined with inflammatory cues from the microenvironment, cooperatively drive enhanced invasion and metastasis (79).

Loss of PTEN or activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway is associated with the progression and metastasis of human prostate cancer (PCa). However, in preclinical mouse models, PTEN deletion alone does not fully reproduce the extensive metastatic burden commonly observed in advanced human disease. Analysis of human prostate cancer (PCa) tissue microarrays revealed substantial activation of the RAS/MAPK pathway in both primary tumors and metastatic lesions. To further investigate, mice carrying a conditionally activatable K-ras (G12D) allele were crossed with a prostate-specific PTEN knockout model. At the same time, RAS activation alone was insufficient to initiate PCa; its combination with PTEN loss markedly accelerated disease progression, driving robust EMT and widespread macrometastasis with complete penetrance. Within these compound mutant prostates, a distinct population of stem/progenitor cells with mesenchymal features was identified, displaying high metastatic potential upon orthotopic transplantation. Importantly, pharmacological inhibition of RAS/MAPK signaling with the MEK inhibitor PD325901 significantly reduced metastasis driven by these stem/progenitor cells. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that RAS/MAPK activation functions as a critical cooperating driver alongside PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway disruption, suggesting that dual targeting of these pathways may provide an effective strategy for preventing metastatic Prostate Cancer (80).

4.2 STAT3 signaling pathway

EMT plays a key role in cancer progression and metastasis across numerous malignancies, and its regulation is closely linked to the STAT3 signaling pathway. In CRC, HOXB8 promotes proliferation, invasion, and EMT through STAT3 activation, while HOXB8 knockdown suppresses tumor growth and reduces EMT marker expression (81). In PDAC, interleukin-6 (IL-6) secreted by PSCs induces EMT via the Stat3/Nrf2 pathway, thereby promoting migration and invasion; inhibition of either pathway significantly reduces these effects (82). In ovarian cancer, the traditional Chinese medicine Guizhi-Fuling Wan (GZFL) suppresses tumor growth and EMT by downregulating STAT3 activity, supporting its potential as a therapeutic agent (83). In triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), the natural compound bufotalin induces apoptosis, inhibits proliferation, and reduces metastasis by targeting STAT3 and modulating EMT markers and matrix remodeling enzymes (84). In PC, combining gemcitabine with the STAT3 inhibitor Stattic enhances cytotoxicity by inducing oxidative stress, mitochondrial apoptosis, and DNA damage, while concurrently reducing EMT and immune evasion through downregulation of PD-L1 and CD47 and inhibition of the Smad2/3 pathway (85). This combination therapy also affects broader signaling networks, including those involving the AKT and β-catenin pathways. These findings highlight the central role of STAT3 in regulating EMT, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance, underscoring its value as a comprehensive therapeutic target across multiple cancer types. TNF-α-inducing protein (Tipα), a recently identified carcinogenic factor secreted by Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), is recognized as a potent inducer of EMT, a key process in cancer cell migration. However, its precise molecular mechanism remains unclear. Growing evidence suggests that aberrant activation of the oncogenic transcription factor STAT3 is a common feature across various types of cancer, including gastric cancer. In SGC7901 gastric cancer cells, Tipα treatment significantly reduced E-cadherin expression while increasing N-cadherin and vimentin expression, accompanied by morphological changes characteristic of EMT. Tipα also enhanced cellular proliferation and migration. Mechanistically, Tipα activates the interleukin-6 (IL-6)/STAT3 signaling pathway, whereas inhibition of this axis reverses Tipα-induced proliferation, migration, and EMT, indicating that Tipα's carcinogenic effects are mediated by IL-6/STAT3 signaling (86).

Lung cancer, the most prevalent cancer type, has a complex and poorly understood pathophysiology, leading to limited therapeutic options and poor prognosis. To clarify the molecular mechanisms driving lung cancer progression, the role of SH2B3 was investigated. SH2B3 expression was significantly reduced in lung cancer tissues and cell lines, whereas TGF-β1 levels were elevated. Low SH2B3 expression was associated with poorer patient outcomes. Functional studies revealed that SH2B3 overexpression suppressed anoikis resistance, proliferation, migration, invasion, and EMT in lung cancer cells, whereas TGF-β1 promoted these malignant traits by downregulating SH2B3. Mechanistically, SH2B3 interacted with JAK2 and SHP2, thereby inhibiting the JAK2/STAT3 and SHP2/Grb2/PI3K/AKT pathways, ultimately reducing EMT and other malignant properties. In vivo experiments confirmed that SH2B3 overexpression significantly restrained lung cancer growth and metastasis. Together, these findings identify SH2B3 as a tumor suppressor in lung cancer that counteracts oncogenic signaling and cellular processes associated with disease progression (87).

The progression and metastasis of CRC and lung cancer involve complex EMT and MET processes tightly regulated by STAT3 signaling. In CRC, STAT3 knockdown increases E-cadherin expression and decreases mesenchymal markers such as N-cadherin and vimentin, thereby reducing invasiveness and enhancing chemosensitivity to fluorouracil. Conversely, STAT3 overexpression promotes EMT and strengthens invasive capacity. ZEB1, a key EMT transcription factor, is upregulated by STAT3 and represses E-cadherin, thereby mediating STAT3-driven invasion. Notably, the expression of both STAT3 and ZEB1 is strongly correlated with advanced TNM stages.

In lung cancer, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) under hypoxic conditions release exosomes containing miR-193a-3p, miR-210-3p, and miR-5100, which activate STAT3 signaling in neighboring cancer cells, inducing EMT and enhancing invasiveness. Among these, miR-193a-3p shows promise as a noninvasive biomarker for diagnosing lung cancer and assessing metastatic potential. Systems biology analyses further reveal that BMSC-derived factors such as LIF and IL-6 selectively phosphorylate STAT3 at serine 727 and tyrosine 705, respectively, thereby regulating EMT-MET transitions and CSC dynamics during early dissemination and pre-metastatic niche formation. Collectively, STAT3 acts as a central regulator of EMT/MET plasticity in CRC and lung cancer, with both direct transcriptional control (via ZEB1) and exosomal miRNA-mediated activation driving tumor invasion, metastasis, and therapy resistance (88-90).

4.3 Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

The anticancer potential of garcinol, a natural compound derived from Garcinia indica, has been the focus of extensive investigation. Previous studies demonstrated its ability to preferentially induce apoptosis in breast cancer cells by blocking the NF-κB signaling pathway. Garcinol has been shown to reverse EMT and induce MET in aggressive TNBC cell lines, MDA-MB-231 and BT-549. This phenotypic switch was characterized by increased expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin and decreased levels of mesenchymal markers, including vimentin, ZEB-1, and ZEB-2. Garcinol also upregulated members of the miR-200 and let-7 families, offering a molecular explanation for MET induction. Significantly, ectopic expression of the NF-κB p65 subunit reduced garcinol-induced apoptosis by converting MET back to EMT, while p65 overexpression and miR-200 inhibition counteracted garcinol’s suppression of cell invasion. Additionally, garcinol treatment promoted β-catenin phosphorylation and inhibited its nuclear localization. These findings were validated in a xenograft mouse model, where garcinol inhibited NF-κB activity, altered miRNA expression, and reduced both vimentin and nuclear β-catenin levels (91).

HCC is one of the most lethal cancers, yet its core genetic mechanisms remain incompletely understood. Genome-wide methylation profiling has identified CLDN3 as an epigenetically regulated gene in cancer. In human HCC, CLDN3 downregulation was detected in 87 of 114 (76.3%) primary tumor samples and was significantly correlated with reduced patient survival (P = 0.021). Multivariate Cox regression further confirmed CLDN3 as an independent prognostic indicator for overall survival (P = 0.014). Loss of CLDN3 expression was observed in 67% of HCC cell lines and was strongly linked to promoter hypermethylation. Restoration of CLDN3 expression in HCC cells suppressed motility, invasiveness, and tumorigenic potential in nude mice. Mechanistically, CLDN3 inhibited metastasis by blocking the Wnt/β-catenin-driven EMT pathway by downregulating key regulators, including GSK3B, CTNNB1, SNAI2, and CDH2 (92).

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is a key regulator of EMT, metastasis, and tumor progression in multiple cancers, including CRC, NSCLC, and gastric cancer. In CRC, RUNX1 is upregulated, promoting EMT and metastasis by directly interacting with β-catenin and enhancing KIT transcription, thereby activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Notably, RUNX1 itself is also regulated by the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, establishing a feedback loop that sustains tumor progression (93). In NSCLC, elevated FOXP3 expression is associated with poor patient prognosis. It promotes tumor proliferation, EMT, and invasion by directly interacting with β-catenin and TCF4, thereby enhancing the transcription of Wnt target genes, including c-Myc and Cyclin D1 (94). In CRC, TM4SF1 is highly expressed and promotes cancer stemness and EMT via the Wnt/β-catenin/c-Myc/Sox2 pathway, while its downregulation significantly suppresses metastasis and tumorigenesis (95). The importance of Wnt signaling within the TME is evident, as stromal Wnt activity, particularly in cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), exerts variable effects on tumor progression. Wnt antagonists such as Sfrp1 suppress tumor growth and EMT by modulating stromal signaling, while leaving tumor-intrinsic Wnt activity unaffected (96). Different CAF subtypes, influenced by Wnt activity, include myofibroblastic CAFs (myCAFs) and inflammatory CAFs (iCAFs), which play opposing roles: myCAFs suppress EMT, while iCAFs promote it. These findings underscore the multifaceted role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in driving EMT and metastasis through both tumor-intrinsic mechanisms and microenvironmental interactions across diverse cancers. Recent research has further identified NANOGP8, KIAA1199, IQGAP1, and DNER as key facilitators of cancer progression, primarily through pathways linked to Wnt/β-catenin signaling and EMT. Notably, NANOGP8, rather than NANOG1, is the dominant contributor to NANOG expression in sphere-forming cancer stem-like cells (CSLCs) in gastric cancer (97). It strongly promotes stemness, EMT, metastasis, chemoresistance, and Wnt signaling activity, positioning it as a key oncogenic regulator and a promising therapeutic target. KIAA1199 is significantly upregulated in gastric cancer, where it correlates with poor prognosis and drives proliferation, invasion, and EMT through activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and MMPs (98).

In PDAC, IQGAP1 acts as an oncogenic scaffold protein that promotes proliferation, migration, invasion, and EMT by increasing Dishevelled2 (DVL2) expression, enhancing β-catenin nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity, and directly binding to both DVL2 and β-catenin; silencing DVL2 attenuates these effects (99).DNER is highly expressed in breast cancer, especially in triple-negative subtypes, where it correlates positively with β-catenin expression and drives EMT, proliferation, metastasis, and resistance to epirubicin-induced apoptosis through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Collectively, these findings underscore the oncogenic roles of NANOGP8, KIAA1199, IQGAP1, and DNER across multiple cancer types, all of which converge on the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway to promote malignant transformation, thereby highlighting their potential as molecular targets for future cancer therapies. Elevated Wnt signaling has been increasingly associated with the initiation and progression of human breast cancer. Activation of the canonical Wnt pathway leads to the formation of a β-catenin-T-cell factor (TCF) transcriptional complex, which is thought to drive EMT, a critical process underlying cancer tissue invasion. However, the precise molecular mechanisms by which the β-catenin-TCF complex induces EMT-like changes have remained unclear. Recent studies show that canonical Wnt signaling promotes tumor cell dedifferentiation and invasive behavior through an Axin2-dependent pathway that stabilizes Snail1, a zinc-finger transcription factor central to both developmental and cancer-associated EMT. Axin2 functions as a nucleocytoplasmic chaperone for GSK3β, the key kinase regulating Snail1 protein stability and activity. The widespread dysregulation of Wnt signaling across cancers underscores the importance of the β-catenin-TCF-Axin2-GSK3β-Snail1 signaling axis, providing critical mechanistic insight into EMT regulation in tumor progression (100).

PC is among the deadliest malignancies, marked by early metastasis and a high mortality rate. Subunits of the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex are recognized as key regulators of tumor development; however, the role of SMARCAD1, a member of this family, in PC remains unclear. Analysis of GEO datasets and immunohistochemical evaluation of patient-derived PC tissues revealed elevated SMARCAD1 expression in tumors, with higher levels correlating with poorer patient survival. Functional studies showed that SMARCAD1 enhances the proliferation, migration, and invasion of PCCs. Mechanistically, SMARCAD1 promotes EMT by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in PC (101).

Extensive studies highlight the central role of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in driving EMT, stemness, metastasis, and chemoresistance across various cancers, including gastric, colorectal, TSCC, and breast cancers. In gastric cancer, VGLL4 functions as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting EMT through negative regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway; its downregulation promotes proliferation, migration, invasion, and apoptosis resistance (102). DVL3 is highly expressed in CRC and is associated with a poor prognosis, promoting EMT, CSLC traits, and multidrug resistance by activating the Wnt/β-catenin/c-Myc/Sox2 pathway. Silencing DVL3 suppresses these malignant properties in both in vitro and in vivo models (103). In cisplatin-resistant TSCC, SOX8 is upregulated, promoting EMT and stem-like properties by directly activating FZD7, which in turn triggers Wnt/β-catenin signaling (104). Silencing SOX8 reduces chemoresistance and CSC-like features, effects that can be partially rescued by β-catenin overexpression. In breast cancer, especially in basal-like subtypes, Wnt signaling is similarly linked to stemness, EMT, and metastatic potential (105). In an orthotopic breast cancer model, inhibition of Wnt signaling through LRP6 suppression reduced self-renewal and metastatic spread, while restoring epithelial marker expression and downregulating EMT-related transcription factors, such as SLUG and TWIST. Collectively, these findings underscore the pivotal role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in orchestrating EMT, cancer stemness, metastasis, and therapy resistance across various malignancies, positioning it as a critical target for therapeutic intervention.

Extensive research highlights the crucial role of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in driving EMT, metastasis, and tumor progression across various cancers, including gastric, ovarian, colorectal, and pancreatic malignancies. In gastric cancer, EphA2 is frequently overexpressed and is strongly correlated with EMT markers and metastatic potential, promoting cell migration and invasion by activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway; this effect can be reversed by pharmacological inhibition of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. In epithelial ovarian cancer, the tumor suppressor TET1 is notably downregulated in advanced stages of the disease. Restoration of TET1 expression suppresses EMT and tumor cell invasion by demethylating and reactivating Wnt pathway antagonists such as DKK1 and SFRP2, thereby effectively blocking β-catenin signaling (106). TUSC3 is upregulated in CRC tissues and drives EMT, proliferation, invasion, and xenograft tumor growth by activating the MAPK, PI3K/Akt, and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways, underscoring its oncogenic role (107). Together, these findings demonstrate that both oncogenic drivers and tumor-suppressive regulators converge on the Wnt/β-catenin pathway to modulate EMT and metastasis, underscoring its therapeutic value across multiple cancers.

EMT is a tightly regulated biological process usually involved in embryonic development and tissue repair, but it becomes dysregulated as cancer progresses. Traditionally, EMT has been viewed as a linear shift from an epithelial to a fully mesenchymal phenotype. However, growing evidence highlights the existence of intermediate or partial EMT states, in which cells acquire mesenchymal traits while still retaining epithelial characteristics. The deubiquitinase USP7 has emerged as a key regulator of this partial EMT phenotype in colon cancer cells. USP7 is markedly overexpressed in colon adenocarcinomas, with its expression correlating with advanced tumor stages. Inhibition or silencing of USP7 significantly reduces mesenchymal marker expression and impairs cancer cell migration. Proteomic analyses have identified the DEAD-box RNA helicase DDX3X as an interacting partner of USP7. Mechanistically, USP7 enhances Wnt/β-catenin signaling by stabilizing DDX3X, thereby promoting invasiveness in CRC cells (103).

Receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIP1), a key mediator of TNF-α signaling, has recently been identified as a novel regulator of canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling, contributing to CRC metastasis. WNT3A treatment progressively increases RIP1 and β-catenin expression, as demonstrated by immunohistochemical analyses of human CRC tissues. These analyses reveal that elevated RIP1 levels correlate with β-catenin expression, tumorigenesis, and metastatic progression. In vivo studies using intravenously injected RIP1-overexpressing CRC cells further demonstrate that RIP1 enhances CRC cell metastatic potential. Mechanistically, WNT3A stimulation promotes direct interaction between RIP1 and β-catenin, stabilizing β-catenin through RIP1-mediated deubiquitination, a process facilitated by suppression of the E3 ligases cIAP1 and cIAP2. Inhibition of cIAP1/2 expression or its ligase activity enhances WNT3A-driven RIP1-β-catenin binding and accumulation, thereby promoting EMT and increasing CRC cell motility and invasion in vitro. Additional experiments confirm the direct interaction between RIP1 and β-catenin, showing that RIP1 disrupts the β-catenin-β-TrCP complex. Collectively, these findings uncover a novel WNT3A-RIP1-β-catenin axis that drives EMT and plays a pivotal role in CRC progression and metastasis (108).

EMT is a key driver of cancer metastasis and therapeutic resistance, orchestrated by intricate regulatory networks, including the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Computational models suggest that coupled feedback loops between ERK and Wnt signaling tightly regulate E-cadherin expression, with RKIP phosphorylation and transcriptional repression serving as pivotal regulators of the switch-like dynamics of EMT. As a well-characterized EMT suppressor, RKIP loss or downregulation is closely linked to increased metastatic potential (109). In breast cancer, PLAGL2 drives adriamycin resistance and EMT by directly upregulating Wnt6 transcription, thereby amplifying Wnt/β-catenin signaling and promoting proliferation, migration, and invasion. Conversely, PLAGL2 silencing restores adriamycin chemosensitivity (110). RCC2, an oncogenic driver in breast cancer, enhances proliferation and migration through Wnt-mediated EMT, with its overexpression linked to unfavorable patient survival (111). Likewise, CCT5 is overexpressed in lymph node-metastatic gastric cancer, where it promotes proliferation, anoikis resistance, and metastasis by binding to the cytoplasmic domain of E-cadherin, thereby disrupting its interaction with β-catenin and activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling (112).

In summary, these studies collectively demonstrate that oncogenic regulators, such as RKIP, PLAGL2, RCC2, and CCT5, drive EMT and cancer progression by modulating the Wnt/β-catenin axis, underscoring this pathway’s central role in tumor aggressiveness and therapy resistance across various malignancies. EMT, a key determinant of cancer metastasis, stemness, and treatment resistance, is tightly orchestrated by multiple signaling pathways, including the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. In colon cancer, intratumoral heterogeneity in Wnt activity gives rise to diverse EMT states, with the transcription factor RUNX2 identified as a critical epigenetic regulator that remodels chromatin, activates EMT-related genes, and amplifies EMT heterogeneity, an effect strongly associated with poor prognosis across cancer types (113). In laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma, SOX2 overexpression drives migration, invasion, and EMT, characterized by reduced E-cadherin and increased mesenchymal markers, primarily through β-catenin activation (114). In PCa and castration-resistant PCa (CRPC), the nuclear receptor NURR1 promotes EMT, stemness, and metastatic progression by directly activating CTNNB1 and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, establishing NURR1 as a potential therapeutic target (115). In gastric cancer, RUNX3 is frequently downregulated and inversely correlated with c-MET expression, a known oncogenic driver. Treatment with the c-MET inhibitor INC280 significantly suppresses proliferation, induces apoptosis, and inhibits Wnt signaling and SNAIL expression in c-MET-amplified, RUNX3-positive diffuse-type gastric cancer cells, underscoring its therapeutic potential (116).

Collectively, these findings underscore the central role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and its transcriptional regulators, RUNX2, SOX2, NURR1, and RUNX3, in driving EMT, metastasis, and therapy resistance across various cancers, highlighting their potential as targets for more effective cancer treatments. STMN2, a key regulator of microtubule disassembly and dynamics, has recently been implicated in cancer progression; however, its role in PDAC remains largely unexplored. In this study, STMN2 was significantly overexpressed in 81 PC tissue samples compared with adjacent normal tissues (54.3% vs. 18.5%; P < 0.01). High expression of STMN2 correlated with aggressive clinical features, including larger tumor size, advanced T stage, lymph node metastasis, and poor prognosis. Elevated STMN2 levels were also strongly associated with cytoplasmic and nuclear β-catenin expression in PCa tissues and cell lines. Functionally, STMN2 overexpression promoted EMT and proliferation in vitro, as evidenced by EMT-like morphological changes, increased motility, modulation of EMT markers (Snail1, E-cadherin, Vimentin), and activation of Cyclin D1 signaling. Pharmacologic inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling using XAV939 attenuated the effects of STMN2 overexpression, while pathway activation with KY19382 restored EMT and proliferation in STMN2-silenced cells. Co-localization of active STMN2 with β-catenin was observed in both cytoplasm and nucleus, and transcriptional regulation of STMN2 by β-catenin/TCF was confirmed through specific binding sites (TTCAAAG). In vivo experiments further demonstrated that STMN2 drives tumor growth by inducing EMT and activating Cyclin D1. Collectively, these findings identify STMN2 as a facilitator of PDAC progression and aggressiveness by promoting EMT and proliferation via a β-catenin/TCF-dependent mechanism (117).

Cervical cancer ranks as the third most common malignancy and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women worldwide. In recent years, EMT has attracted increasing attention for its critical role in tumor metastasis. Cysteine-rich intestinal protein 1 (CRIP1) exhibits variable expression across different human cancers; however, its role in cervical cancer remains unclear. Initial findings revealed significantly higher CRIP1 expression in CC tissues compared with adjacent noncancerous tissues. This was further confirmed through qPCR and western blot analyses, which demonstrated elevated CRIP1 levels in CC cell lines. Functional assays using CRIP1 overexpression and siRNA knockdown showed that CRIP1 markedly enhances cell motility and invasion in vitro (P < 0.01). Mechanistic studies indicated that CRIP1 regulates EMT, as reflected by changes in EMT marker expression. Immunohistochemical analysis further revealed significant co-expression of CRIP1 and β-catenin in cervical cancer tissues (P < 0.01). Additionally, CRIP1 upregulated c-Myc, Cyclin D1, and cytoplasmic β-catenin, implicating it in the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (118).

Extensive research across multiple cancer types highlights the critical role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in regulating EMT, tumor progression, metastasis, and clinical outcomes. In TNBC, NuSAP1 is markedly overexpressed and associated with poor survival, driving cell proliferation and invasion by activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and inducing EMT markers, including Cyclin D1, vimentin, Slug, and Twist (113). Similarly, Hsp90ab1 is upregulated in gastric cancer, where it promotes proliferation and metastasis by binding to and stabilizing LRP5, thereby enhancing Wnt/β-catenin signaling and driving the upregulation of mesenchymal markers (119). Conversely, EFEMP2 acts as a tumor suppressor in bladder cancer; reduced expression correlates with poor prognosis, advanced stage, and grade, as well as with increased EMT and Wnt/β-catenin activity. Its overexpression inhibits proliferation and metastasis (120). In epithelial ovarian cancer, GOLPH3 functions as an oncogene, driving EMT and metastasis via Wnt/β-catenin signaling and upregulating N-cadherin, Snail, cyclin D1, and c-Myc, with EDD identified as a potential downstream effector (121). Pharmacological modulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, using activators such as LiCl or inhibitors like XAV939, underscores the central role of this pathway in regulating EMT. Collectively, these findings identify Wnt/β-catenin as a key oncogenic driver linking EMT to cancer progression in TNBC, gastric cancer, bladder cancer, and epithelial ovarian cancer, while also highlighting NuSAP1, Hsp90ab1, EFEMP2, GOLPH3, and EDD as critical regulators and potential therapeutic targets.

4.4. TGF-β signaling pathway

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) plays a complex, context-dependent role in cancer, acting as both a tumor suppressor and promoter. In early-stage tumors, TGF-β can inhibit proliferation; however, some CRC cells evade this control by downregulating TGF-β receptors and disrupting Smad signaling, including Smad4 nuclear translocation. At later stages, TGF-β promotes tumor progression by driving stromal remodeling, angiogenesis, and immune suppression. Secreted in a latent form by cancer cells, TGF-β is activated within the TME by regulatory T (Treg) cells expressing αvβ8 integrin, thereby suppressing cytotoxic T cell activity and facilitating tumor growth. In addition, TGF-β signaling intersects with p53 pathways by repressing REGγ, a proteasome activator that promotes the degradation of tumor suppressors, including p53 and p21. In cancers with mutant p53, this regulation is lost, leading to elevated REGγ expression, increased proteasome activity, and enhanced tumorigenesis and therapy resistance. Collectively, these insights highlight TGF-β’s dual function in cancer, both modulating the intrinsic behavior of tumor cells and shaping an immunosuppressive microenvironment through its signaling and proteolytic interactions (122-124). TGF-β plays a paradoxical, context-dependent role in cancer, functioning both as a tumor suppressor and a promoter of cancer. In the early stages of tumorigenesis, TGF-β acts as a cytostatic and pro-apoptotic factor, creating a crucial barrier against malignant transformation, most evident in PTEN-deficient prostate tumors, where TGF-β signaling restrains progression until overcome by modulators such as COUP-TFII, which blocks SMAD4-dependent transcription and drives metastasis. As tumors evolve, however, TGF-β signaling is frequently co-opted to promote immune evasion, stromal remodeling, and angiogenesis. Tumor cells often upregulate TGF-β to suppress both adaptive and innate immune responses and to activate CAFs, thereby generating an immunosuppressive microenvironment. This reprogramming aligns with a distinct ECM transcriptional profile linked to poor prognosis and resistance to immunotherapies, including PD-1 inhibitors.

Moreover, genetic alterations in key regulators, such as TP53, SMAD4, and MYC, further intersect with TGF-β pathways, thereby amplifying tumor aggressiveness. These insights have sparked growing interest in therapeutic strategies that aim to inhibit TGF-β signaling, thereby restoring immune surveillance and enhancing the efficacy of immunotherapy across various cancer types (125-128). Initially, TGF-β suppresses carcinogenesis by inhibiting cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis; however, as tumors progress, cancer cells and the surrounding stroma hijack TGF-β signaling to drive immune evasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis. Within the TME, CAFs are significant sources of TGF-β, dampening cytotoxic and T helper 1 (TH1) immune responses while fostering a fibrotic, immunosuppressive barrier that limits the effectiveness of immune checkpoint therapies such as PD-L1 blockade. Recent studies suggest that inhibiting TGF-β signaling, particularly in CD4+ T cells using agents like the CD4 TGF-β Trap (4T-Trap), can remodel the TME by enhancing TH2-mediated immunity, normalizing vasculature, and promoting tumor cell apoptosis.

Furthermore, combining TGF-β inhibition with VEGF blockade or checkpoint inhibitors has demonstrated synergistic benefits amplifying anti-tumor immunity and enhancing therapeutic response. Together, these insights highlight the central yet complex role of TGF-β in tumor progression and immune regulation, rendering it a compelling yet challenging target for cancer therapy (129-132). Epithelial and hematopoietic progenitor cells are particularly susceptible to transformation due to their high turnover rates and vulnerability to genetic and epigenetic alterations, including dysregulated responses to growth factors such as TGF-β. TGF-β signaling plays a dual role in cancer, acting as a tumor suppressor in some contexts while promoting tumor progression in others through its complex autocrine and paracrine effects on both tumor cells and the surrounding microenvironment (133). The immune system combats cancer through type 1 immunity, which directly eradicates malignant cells, and type 2 immunity, which supports tissue repair and containment. Loss of TGF-β receptor 2 in CD4+ T cells initiates an IL-4-dependent type 2 response that remodels vasculature, induces hypoxia in cancer cells, and suppresses tumor growth through host-mediated mechanisms (134).

Hypoxia is a critical driver of EMT, invasion, and metastasis in solid tumors. Recent studies have highlighted the role of alternative splicing (AS) in this process, particularly in breast cancer, where hypoxia-induced suppression of the splicing regulator ESRP1 leads to the expression of the pro-metastatic hMENAΔ11a isoform (135). This process is driven by hypoxia-activated TGF-β signaling, which increases the expression of SLUG and RBFOX2, transcriptional repressors of ESRP1. Additionally, RBFOX2 physically interacts with SLUG. Under hypoxic conditions, exosomal TGF-β release amplifies this cascade, inducing broad changes in alternative splicing that promote EMT (136). In lung cancer, TGF-β1-mediated EMT involves the upregulation of neuropilin-2 (NRP2), a receptor for the tumor suppressor SEMA3F, through a TβRI-dependent but SMAD-independent mechanism that engages the ERK and AKT pathways. Elevated NRP2 promotes tumor cell migration, invasion, and morphological changes, which correlate with E-cadherin loss and higher tumor grade. In TNBC, ICAM1 plays a crucial role in bone metastasis by inducing EMT via the TGF-β/SMAD signaling pathway, a process facilitated by integrin interactions (137). High ICAM1 expression correlates with poor prognosis, whereas its inhibition reduces bone metastasis in vivo. In CRC, TGF-β exerts dual functions as both a tumor suppressor and promoter, which are modulated by NDRG2, a gene induced by TGF-β through Sp1 activation and the relief of c-Myc/Miz-1 repression (138). Although NDRG2 normally inhibits EMT and cell invasion, its silencing through promoter hypermethylation weakens the growth-suppressive effects of TGF-β, ultimately facilitating metastasis. Overall, these findings highlight TGF-β as a key regulator of EMT and metastatic progression in various cancers, with factors such as hypoxia, splicing regulators, and epigenetic modifications shaping its dual role as either a tumor suppressor or promoter, depending on the cellular context. Histone methylation is a crucial regulatory mechanism in both normal cellular function and disease, especially in cancer progression. In TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), the Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) component EED, responsible for methylating histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27), acts as an essential modulator. When TGF-β initiates EMT, EED expression rises, and its absence interferes with the typical morphological transformations associated with EMT. EED inhibition also counteracts TGF-β-mediated alterations in the expression of essential EMT-related genes, including CDH1, ZEB1, ZEB2, and the miRNA-200 (miR-200) family. Chromatin immunoprecipitation studies further demonstrate that EED contributes to TGF-β-induced transcriptional repression of CDH1 and miR-200 by modulating H3K27 methylation and influencing EZH2 binding at their respective regulatory regions (139).

AlkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5), an RNA N6-methyladenosine (m6A) demethylase, is a critical regulator of development and disease. The role of TGF-β in driving EMT and metastasis in NSCLC, however, remains incompletely understood. In metastatic NSCLC, ALKBH5 expression is markedly reduced. Functionally, ALKBH5 overexpression suppresses TGF-β-induced EMT and invasion in NSCLC cells, while its knockdown enhances these malignant traits. In vivo, ALKBH5 overexpression also limits TGF-β-driven metastasis. Mechanistically, ALKBH5 reduces TGFβR2 and SMAD3 expression and mRNA stability, while increasing SMAD6 levels; knockdown produces the opposite effects. ALKBH5 also influences SMAD3 phosphorylation, reducing SMAD3 activation upon ALKBH5 overexpression and enhancing it upon ALKBH5 silencing. The m6A-binding proteins YTHDF1 and YTHDF3 boost the expression of TGFβR2 and SMAD3, while YTHDF2 inhibits SMAD6 expression. Together, these actions strengthen TGF-β-driven epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cell invasion. By removing m6A marks, ALKBH5 destabilizes YTHDF1/3-associated TGFβR2 and SMAD3 transcripts but simultaneously stabilizes SMAD6 mRNA by preventing its degradation through YTHDF2. These findings establish ALKBH5 as a negative regulator of TGF-β-induced EMT and metastasis in NSCLC, operating through a YTHDF1/2/3-dependent mechanism (140).