REVIEW ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS

Advancing Precision Oncology Using Data-Driven Machine Learning Approaches

Özge Tatli1# and Julhash U. Kazi2,3,4#

Received 2025 Sept 8

Accepted 2025 Oct 31

Epub ahead of print: December 2025

Published in issue 2026 Feb 15

Correspondence: Özge Tatli ozge.tatli@medeniyet.edu.tr

Julhash U. Kazi kazi.uddin@med.lu.se

The author’s information is available at the end of the article.

© 2026 The Author(s). Published by GCINC Press. Open Access licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. To view a copy: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

Precision oncology is being transformed by the integration of advanced machine learning (ML) methods and extensive biomedical data from genomics, imaging, proteomics, and clinical records. ML techniques, including supervised, unsupervised, deep learning, and reinforcement learning, have progressed from experimental tools to robust systems that identify clinically actionable biomarkers, refine prognosis, and guide personalized therapies. Deep learning models now achieve expert-level performance in tumor detection, grading, and outcome prediction from digital pathology and radiological images, improving diagnostic precision and therapeutic decision-making. Multi-modal and graph-based fusion networks enable the creation of patient-specific digital twins that simulate treatment responses and optimize therapeutic strategies. Data-centric methodologies such as federated learning, differential privacy, and synthetic data generation address challenges related to data sharing and patient privacy. Additionally, large language models trained on biomedical literature are increasingly integrating structured and unstructured clinical data, thereby fostering hypothesis generation and natural language–based decision support. However, challenges, including data heterogeneity, interpretability, algorithmic bias, and regulatory and ethical constraints, remain. Rigorous benchmarking, explainable AI methods, and prospective multi-center trials are essential for validating ML tools and establishing clinician trust. This review discusses recent developments in next-generation ML for precision oncology.

Keywords: Personalized medicine; Precision oncology, predictive analytics, pharmacogenomics, biomarker, computational pathology, artificial intelligence, large language models.

1. Introduction

The landscape of oncology has undergone a profound transformation over recent decades, shifting from an empirical discipline to one increasingly guided by both molecular and computational methodologies (1, 2). Central to this evolution is precision oncology, also referred to as personalized oncology, a paradigm aiming to customize cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment to the unique biological attributes of individual patients and their tumors (3). This personalized approach contrasts starkly with the conventional "one-size-fits-all" model, which often results in variable therapeutic efficacy and avoidable toxicities (4). This transformation has been catalyzed by successive waves of high-throughput technologies, including next-generation DNA/RNA sequencing, single-cell and spatial omics, quantitative mass spectrometry proteomics, high-content imaging, and whole-slide digital pathology, which generate petabyte-scale, multimodal datasets (5). These repositories illuminate the molecular circuitry underlying oncogenesis and drug resistance; however, their dimensionality, heterogeneity, and noise exceed the analytical capacity of classical statistics or unaided human reasoning.

Machine learning (ML), a major branch of artificial intelligence (AI), provides the algorithmic machinery required to convert such complex data into actionable knowledge. By iteratively learning from examples rather than explicit programming, ML systems discover latent structure, derive discriminative features, and yield predictive or generative models that can be continuously refined as new data accrue. The convergence of high-resolution biomedical data with ML has introduced a new phase of precision oncology characterized by more accurate diagnostics, finer-grained prognostication, and data-guided therapy selection (6). Methodologically, the field has progressed from early supervised classifiers that operated on hand-crafted features to deep neural networks capable of end-to-end representation learning directly from raw images, sequences, or signals. Unsupervised and self-supervised paradigms now uncover tumor subtypes de novo, while reinforcement learning frameworks optimize sequential decisions such as radiotherapy beam arrangement or adaptive dosing schedules (7). Generative adversarial networks and diffusion models produce synthetic multi-omics records or imaging studies to augment limited cohorts and to simulate patient-specific drug responses, whereas emerging “digital twin” platforms integrate mechanistic and statistical models to predict disease trajectories and test virtual interventions (8). Building on these methodological advancements, ML applications have rapidly transitioned into clinical practice, influencing numerous aspects of cancer care.

Clinically, ML applications have profoundly impacted the entire cancer care continuum. In diagnostics, ML algorithms have achieved expert-level performance in recognizing subtle malignancy-associated patterns in radiologic and digital pathology images (9, 10). Prognostically, ML models integrate various data modalities to stratify patients into precise risk profiles and predict outcomes more accurately than traditional scoring systems. Therapeutically, ML facilitates personalized treatment selection by leveraging extensive molecular profiles and historical clinical responses, thereby improving therapeutic efficacy and minimizing side effects (11-14). Despite notable achievements, integrating ML into routine oncology practice faces substantial challenges. Technical barriers include data heterogeneity, interoperability issues, and the need for rigorous validation across diverse patient populations. Model interpretability remains a technical issue, particularly with complex "black-box" algorithms that lack transparency (15). Ethical considerations, such as algorithmic bias, data privacy, and equitable access, further complicate the translation of ML innovations from research environments into clinical practice (11). To navigate these complexities, it is essential to analyze specific methodologies and their applications within the evolving oncology landscape.

This review provides an analysis of current applications and emerging trends in ML-driven precision oncology. We begin by discussing methodologies relevant to oncology, then examine data modalities and integration techniques. Subsequently, we illustrate how these approaches are being translated into specific clinical applications across different cancer types and treatment modalities, highlighting the progression from foundational methods to direct impacts on patient care.

2. Catalysts for the Adoption of Machine Learning in Oncology

Over the past quarter-century, ML in oncology has progressed from proof-of-concept classifiers built on tens of samples to regulated software that now guides diagnostic and therapeutic choices for millions of patients. The seminal demonstration that gene-expression signatures could discriminate acute myeloid from acute lymphoblastic leukemia (AML vs ALL) using a handful of microarray profiles marked the field’s starting point. Yet, the study’s training set of 38 cases and its absence of external validation typified the limitations of early, feature-engineered, supervised models (16). Several convergent developments catalyzed the transition to clinically applicable ML. First, exponential growth in affordable graphical-processing-unit (GPU) and cloud computing provided the raw throughput required for deep architectures. Second, data standardization initiatives, such as The Cancer Genome Atlas Program (TCGA), the AACR Project GENIE (17), and the NHS/Genomics England 100,000 Genomes initiative (18), have created diverse, high-quality training corpora that mitigate overfitting and enable cross-institutional benchmarking. Third, common data models and interoperable APIs integrated imaging, molecular, and clinical records, allowing multimodal learning pipelines to be embedded within hospital information systems (19).

3. Supervised learning approaches and applications

Supervised learning remains the mainstay of ML deployments in precision oncology because most clinically actionable tasks, such as diagnostic categorization, risk stratification, and response prediction, can be framed as classification or regression problems. In supervised learning, algorithms are trained on labeled datasets in which the desired output is known, enabling the model to learn mappings from input features to target variables (20-23). Early work relied on feature-engineered algorithms, such as support vector machines (SVMs), random forests (RFs), and gradient boosting machines (GBMs) (24). For instance, SVMs have demonstrated efficacy in classifying cancer subtypes based on gene expression profiles (25). At the same time, RFs have been employed for feature selection in high-dimensional genomic data to identify clinically relevant biomarkers (26). More recently, extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) models have delivered state-of-the-art prognostic nomograms that integrate clinicopathological and multi-omic variables. For example, an XGBoost-based bladder cancer model improved the prediction of three- and five-year cancer-specific mortality compared with conventional Cox models in a 10,000-patient multicenter registry (27).

The advent of deep supervised architectures expanded supervised learning from tabular omics to raw, high-dimensional modalities. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) now interrogate radiographs, computed tomography volumes, and whole-slide histology at sub-human error rates, provided that the training data are appropriately curated and stain-normalized (28). In digital pathology, CNN-based assistants standardize quantitative immunohistochemistry (IHC). Large, multi-institutional datasets with >185,000 breast cancer images for Ki-67/ER/PR/HER2 have demonstrated that automated scoring substantially reduces interobserver variability relative to manual assessment (29). Comparable gains have been reported for PD-L1 evaluation in non-small cell lung carcinoma, where AI algorithms achieve higher consistency and reproducibility than pathologists across different antibody clones and scoring thresholds (30). These tools underpin clinical decisions on checkpoint-inhibitor eligibility and HER2-targeted therapy, illustrating the direct translational impact of supervised learning.

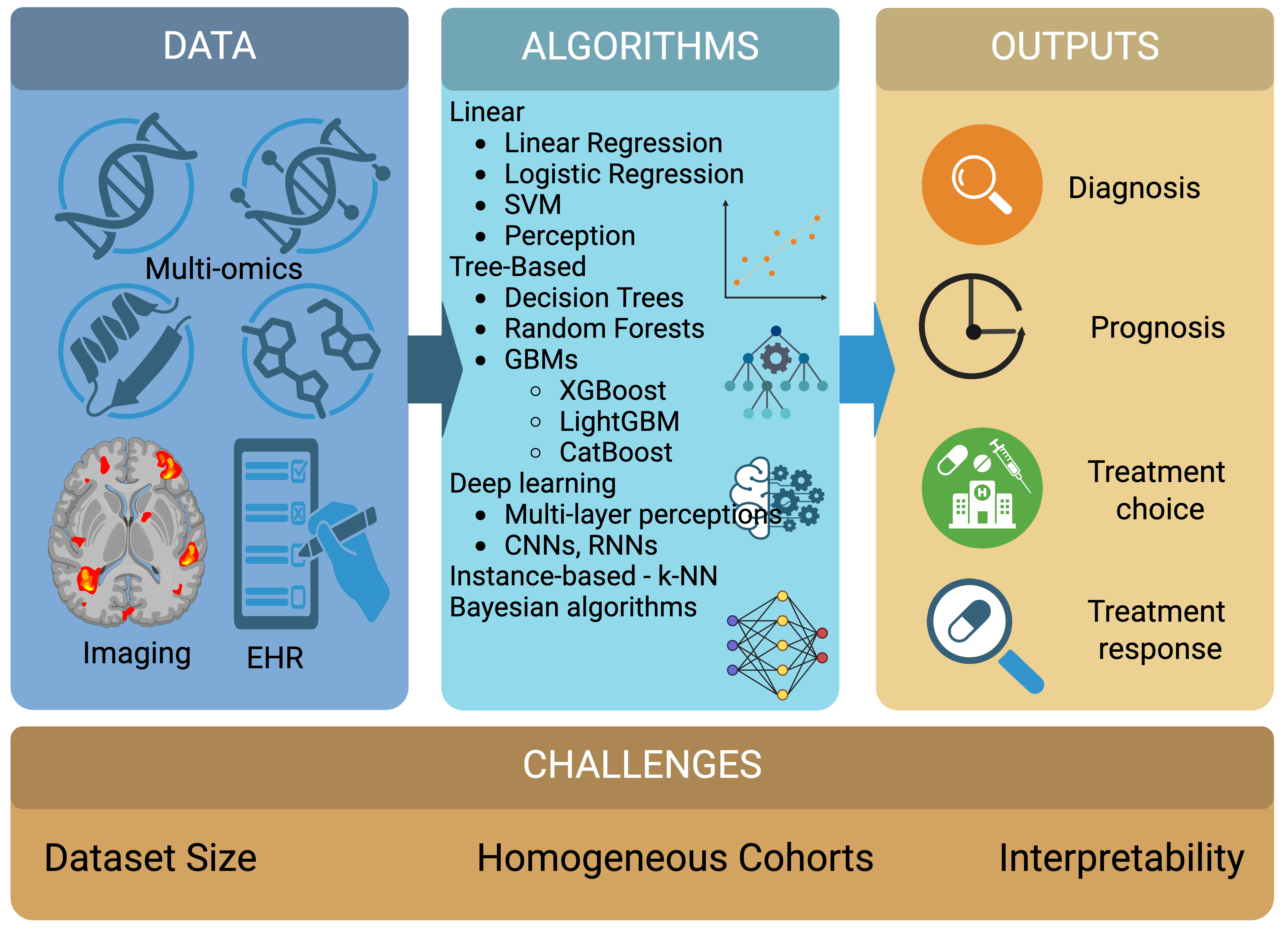

Nevertheless, supervised pipelines continue to face persistent challenges (Figure 1). High predictive accuracy demands large, well-annotated datasets that are costly to assemble. Models trained on homogeneous cohorts may overfit and fail to generalize across different ancestries or data acquisition platforms (31-33). This risk is exacerbated by class imbalance, particularly for rare mutational subtypes. Moreover, the opaque “black box” logic of many deep ensembles complicates biological interpretation and regulatory scrutiny, necessitating complementary explainability frameworks, rigorous external validation, and prospective, multi-center trials before supervised models can be entrusted with high-stakes oncological decisions (34, 35).

Figure 1. Supervised learning.

Schematic overview of supervised-learning workflows in precision oncology, illustrating the progression from diverse key data inputs, including multi-omics profiles, medical imaging, and electronic health records, through representative algorithm families to clinically actionable outputs in cancer diagnosis, prognosis, treatment selection, and treatment-response prediction, while underscoring persistent challenges related to limited dataset scale, data heterogeneity, and model interpretability that continue to constrain clinical translation. Created in BioRender https://BioRender.com/6gw9ga2.

4. Unsupervised learning for pattern discovery

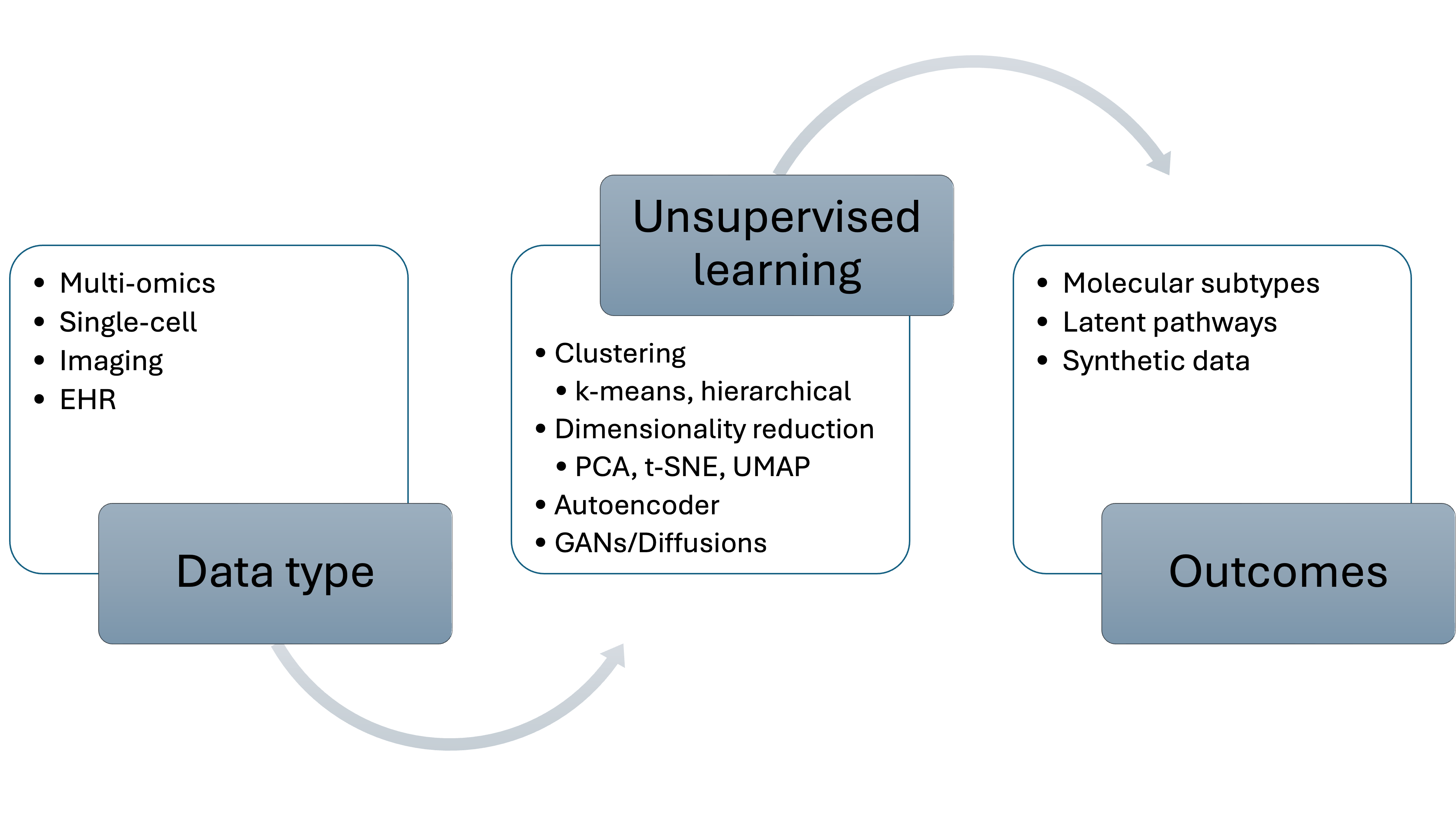

Unsupervised learning approaches have emerged as complements to supervised methods in precision oncology, particularly for exploratory data analysis, patient stratification, and the discovery of novel disease subtypes (Figure 2). Unlike supervised learning, unsupervised methods do not require labeled outcomes; instead, they focus on identifying intrinsic patterns, structures, and relationships within data. Classical clustering algorithms, such as k-means, agglomerative or spectral hierarchical clustering, and density-based methods, including DBSCAN, were initially used to partition gene-expression matrices, culminating in the seminal identification of the luminal A, luminal B, HER2-enriched, and basal-like breast cancer subtypes, which display distinct biology and treatment sensitivity (36). Contemporary studies extend this strategy to semi-supervised learning using an autoencoder (37).

Dimensionality reduction techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA), t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE), and uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) are widely used tools for visualizing and analyzing high-dimensional oncological data. PCA remains a workhorse for bulk omics, but nonlinear techniques, such as t-SNE and UMAP, are now standard for visualizing single-cell and spatial-omics data, where they preserve local neighborhood structure and expose rare cell states or micro-environmental niches that are invisible in higher dimensions (38). Interactive visual analytics platforms built upon these embeddings facilitate intuitive exploration by clinicians and biologists.

Deep representation learning, such as autoencoders (including variational and graph variants), compresses multi-modal cancer data into low-dimensional latent spaces that disentangle tumor-intrinsic biology from technical noise. Latent factors extracted from RNA-seq or methylation matrices often correspond to hallmark pathways and have been shown to stratify patients independently of traditional staging systems (39). In spatial transcriptomics, coupled autoencoder–graph frameworks simultaneously model gene co-expression and physical proximity to reconstruct tissue architecture and identify spatially organized cell communities (40). Generative adversarial networks (GANs) and, more recently, diffusion models synthesize realistic histopathology patches, radiographic volumes, and even multi-omics profiles (41, 42). These synthetic cohorts mitigate class imbalance and data scarcity problems, enhancing the performance and calibration of downstream supervised classifiers without exposing patient-identifiable information. Because purely unsupervised clusters may lack immediate clinical relevance, recent work couples representation learning with sparse outcome labels, such as survival-guided clustering or outcome-constrained variational autoencoders, to align latent structure with prognostic endpoints while retaining the data-efficiency advantages of unsupervised learning (43). These approaches hold promise for rare tumors where annotated cohorts are intrinsically small.

Taken together, unsupervised and semi-supervised methodologies complement supervised pipelines by exposing hidden biological heterogeneity, informing biomarker discovery, and generating synthetic data to strengthen model generalizability, thereby expanding the evidentiary foundation of precision oncology. However, unsupervised learning is not without its specific limitations. A primary challenge is that the generated clusters or latent features may not always align with clinically relevant endpoints, requiring further validation to ensure their utility (44). Furthermore, results can be sensitive to the choice of algorithms and hyperparameters, leading to reproducibility issues (45). Interpreting what these data-driven subtypes represent biologically also requires downstream analysis, bridging the gap between computational patterns and actionable clinical observations (46).

Figure 2. Schematic overview of unsupervised-learning workflows in precision oncology, depicting the flow from core data inputs such as multi-omics profiles, radiological or histopathology imaging, and single-cell measurements through representative unsupervised algorithms (clustering methods such as k-means and hierarchical approaches; dimensionality-reduction techniques including PCA, t-SNE, and UMAP; deep-representation models like autoencoders; and generative frameworks such as GANs or diffusion models) to key biological or translational outputs, namely data-driven molecular subtypes, latent pathway or cell-state signatures, and privacy-preserving synthetic datasets.

5. Deep learning architectures in precision oncology

Building upon the core learning paradigms of supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning, the subsequent discussion is organized around the specific deep learning (DL) architectures that have proven vital in oncology. It is essential to note that DL is not a separate paradigm but rather a suite of multi-layered architectures that have redefined the capabilities within each paradigm. Its ability to process unstructured, high-dimensional biomedical information, such as radiological volumes, whole-slide images, and nucleotide sequences, has positioned DL as a major driver of recent progress in precision oncology, often complementing or outperforming traditional feature-engineered pipelines in terms of accuracy and clinical applicability (47-49). The following will detail these key architectures, including CNN, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN), Transformers, and Graph Neural Networks (GNN), and their transformative applications.

CNNs have demonstrated remarkable success in cancer imaging applications (50). Across cross-sectional CT, MR, and PET, as well as digital pathology, CNN-based detectors have demonstrated performance comparable to that of subspecialists for tumor localization, grading, and survival prediction (51). In histopathology, weakly supervised CNNs have demonstrated strong agreement with pathologist assessments in PD-L1 tumor-proportion scoring, achieving area under the curve (AUC) values above 0.90 and intraclass correlation coefficients around 0.96 in extensive validation studies, thereby reducing inter-observer variability that complicates immunotherapy triage (52, 53).

Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and their gated variants, such as long short-term memory (LSTM) models, are widely used to model temporal structure in clinical data, including event ordering, treatment sequences, and symptom evolution. Several studies have demonstrated that LSTM-based survival models can effectively capture longitudinal risk dynamics and outperform traditional Cox approaches in oncology settings. For example, Qu et al. showed that an LSTM-Cox architecture achieved higher prognostic accuracy than standard Cox regression in predicting cancer survival outcomes, highlighting the utility of recurrent deep learning methods for sequence-based clinical prediction tasks (54).

Similar architectures predict symptom exacerbation months in advance from electronic health record time series, enabling preemptive supportive care (55). Transformer-based architectures, initially developed for natural language processing tasks, have recently been adapted for various oncological applications. Vision Transformers (ViTs), which replace convolution with self-attention, are increasingly used to underpin organ-site-agnostic cancer-screening tools and outperform ResNet baselines in brain-tumor MRI classification (56, 57). Sequence-focused Transformers pre-trained on billions of nucleotides achieve state-of-the-art pathogenic-variant prioritization and transfer efficiently to low-label somatic-mutation tasks (58).

GNNs represent another emerging DL architecture in precision oncology. These architectures are designed to process graph-structured data, making them well-suited to modeling complex biological networks, such as protein-protein interactions, gene regulatory networks, and drug-target interactions. Explainable GNNs, such as XGDP, accurately predict ex vivo drug responses while simultaneously highlighting mechanism-of-action subnetworks (59). Furthermore, modular graph architectures also improve IC₅₀ prediction across more than 1,000 cell-line–compound pairs compared with fully connected networks (60). Reflecting the rapid advancements in this area, more recent studies have employed explainable GNN frameworks to integrate multi-omics data with protein interaction networks, thereby improving the identification of cancer driver genes (61). Furthermore, transformer-based models that leverage graph representation learning are now being used to interpret the importance of multi-omic features and network structures, achieving state-of-the-art performance in cancer gene prediction (62). These advanced applications suggest the growing role of GNNs in creating more interpretable predictive models for precision oncology.

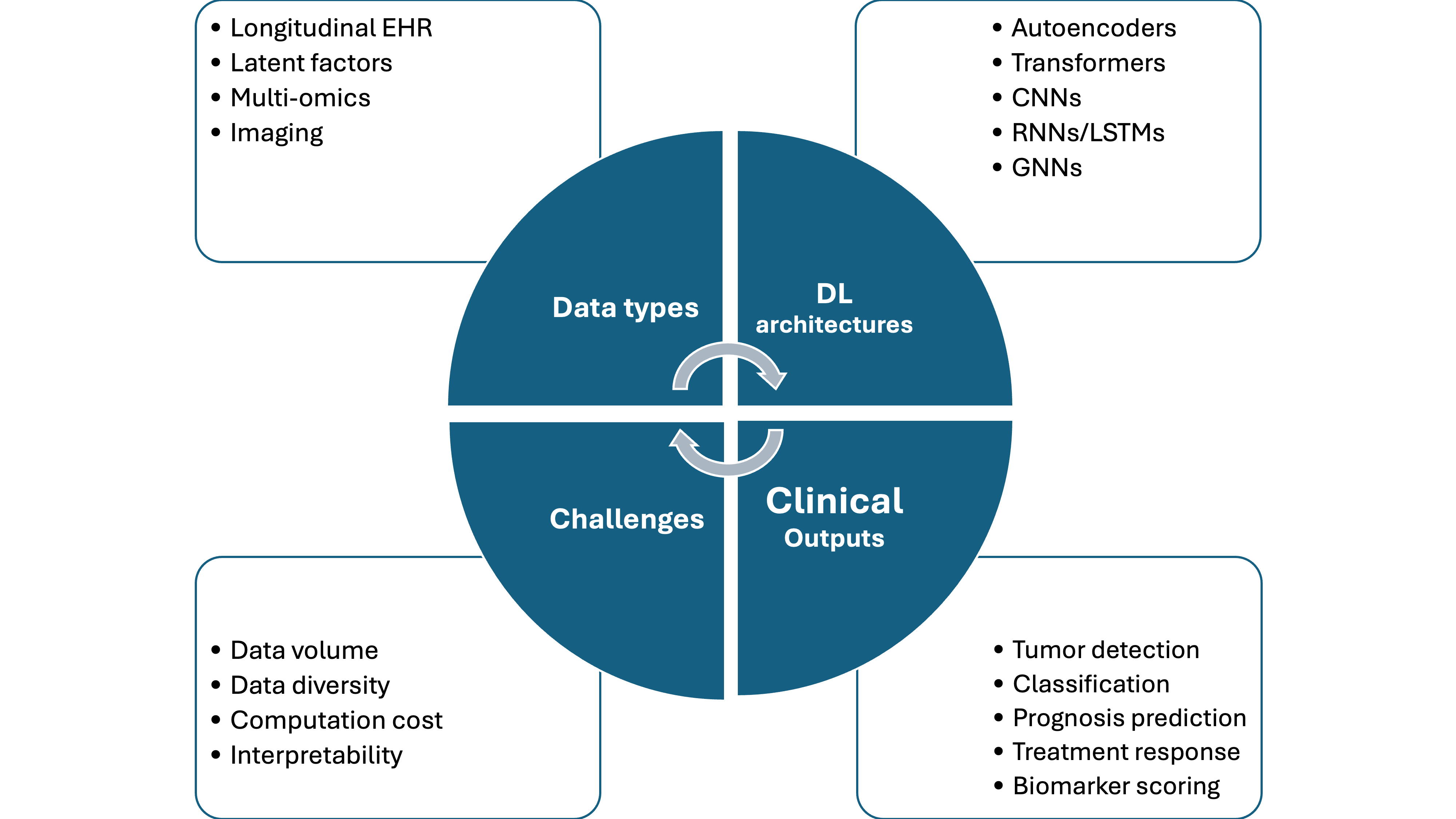

Despite their impressive performance, DL approaches in oncology face several persistent challenges (Figure 3). These include data dependency, computational demands, and interpretability. Strategies such as federated learning and transfer learning mitigate the limitations of small cohort sizes, while sparsity-inducing methods and knowledge distillation reduce inference costs. Interpretability efforts can be broadly categorized into three methodological approaches: feature attribution (e.g., saliency maps, Grad-CAM), counterfactual reasoning (e.g., contrastive explanations), and inherently interpretable architectures (e.g., attention-based or prototype-driven models). While these methods help uncover model reasoning, their reliability remains an open question, as studies have shown that visual explanations may vary with input perturbations or model architecture (63-65). Therefore, caution is warranted in clinical deployment. For clinician-facing applications, we advocate using explainability outputs as supportive cues rather than decision-makers, and suggest that explanations be accompanied by standardized uncertainty metrics where possible. These interpretability tools are increasingly recognized as prerequisites for regulatory approval and clinician trust. Together, these innovations aim to transform DL from an experimental powerhouse into a transparent, clinically deployable component of precision-oncology workflows (66, 67).

Figure 3. Summary of deep-learning workflows in precision oncology. The diagram traces the pipeline from major biomedical data sources (diagnostic imaging, genomic and transcriptomic profiles, longitudinal electronic-health-record sequences) through representative deep-learning architectures such as CNNs, RNNs/LSTMs, vision- and sequence-oriented transformers, GNNs, and autoencoder or other generative models, to principal clinical outputs, including tumor detection or classification, prognostic risk estimation, treatment-response and drug-synergy prediction, and quantitative biomarker scoring. It further lists system-level challenges that constrain deployment, such as requirements for large and diverse datasets, computational cost, and the limited interpretability of complex model decisions.

Although most clinical DL applications in oncology are supervised, aimed at predicting expert-labeled outcomes, other paradigms play supporting roles. Self-supervised learning is widely used to pre-train models on unlabeled data, while reinforcement learning is an emerging approach for optimizing treatment strategies. Table 1 focuses on the primary DL architectures, summarizing their distinct strengths and applications.

Table 1. A comparative overview of key DL architectures in precision oncology.

| Architecture | Core Strength | Common Data | Primary Task in Oncology |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | Analyzing visual patterns and spatial data. | Medical scans (CT, MRI) Digital microscope slides |

Diagnosis: Finding and grading tumors. Prognosis: Predicting outcomes from images. Treatment Selection: Scoring biomarkers. |

| RNN/LSTM | Understanding sequences and how data evolves over time. | Electronic Health Records (EHRs) Patient symptom timelines |

Prognosis: Forecasting future events like cancer

recurrence. Symptom Management: Predicting symptom flare-ups. |

| Transformer | Identifying context and relationships in long sequences. | Genomic sequences (DNA, RNA) Medical images |

Screening & Diagnosis: Classifying disease from

complex data. Risk Assessment: Pinpointing high-risk genetic mutations. |

| GNN | Modeling complex networks and relationships between entities. | Biological networks (protein interactions) Molecular structures |

Treatment Selection: Predicting a tumor's response

to a drug. Biomarker Discovery: Finding influential genes in cancer pathways. |

6. Reinforcement learning frameworks for treatment optimization

Reinforcement learning (RL) addresses sequential decision-making under uncertainty, a fundamental feature of cancer therapy, where clinicians balance tumor control against cumulative toxicity while adapting to evolving patient physiology (68). In RL, an agent observes the current state, such as tumor burden, hematologic indices, and pharmacodynamic markers, executes an action like dose adjustment, drug switch, or schedule adjustment, and receives a reward that quantifies clinical benefit or harm. By iteratively maximizing the long-term expected reward, the agent converges on a dosing or scheduling policy tailored to the individual (69).

The application of RL in precision oncology is still in its early stages, but it shows considerable promise for several use cases. Proof-of-concept studies have cast standard regimens as Markov-decision processes and used Q-learning or actor–critic algorithms to refine chemotherapy or radiotherapy schedules, demonstrating the capacity to maintain oncological control (70-72). Model-free deep RL has likewise generated patient-specific adaptive‐dose policies for multi-cycle chemotherapy, outperforming oncologist-defined heuristics in retrospective simulations (73). More recently, RL has been investigated for optimizing immunotherapy and targeted therapy approaches, which often involve complex decision-making regarding treatment initiation, duration, and combinations (74). The dynamic nature of RL makes it well-suited to adapting treatment strategies based on evolving patient responses and biomarker profiles, thereby enabling more personalized and effective cancer care (75).

The integration of RL with patient-specific digital twins represents a particularly promising direction for precision oncology. Coupling RL with physics- and biology-informed digital twins allows safe policy exploration. Patient-specific ordinary differential equation models of tumor-immune eco-dynamics or pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) systems serve as simulators, allowing RL to test millions of dosing trajectories without patient risk, and then transfer the learned policy to the clinic with continual online updating (71, 76). Furthermore, Deep RL planners have been applied to beam-angle selection and adaptive fractionation, achieving organ-at-risk sparing comparable to expert physicists while reducing planning time by an order of magnitude (77). Multi-agent RL further coordinates combined-modality regimens, jointly selecting radiotherapy dose and concurrent systemic therapy (7). These approaches could reduce the risks associated with trial-and-error treatment adjustments and accelerate the identification of optimal therapeutic strategies for individual patients.

The clinical implementation of RL in precision oncology faces challenges that temper a purely optimistic outlook. Many studies suggest that RL algorithms are highly sample-inefficient, requiring a volume of interactions that is impractical in clinical settings defined by small patient cohorts and delayed outcomes (78). Moreover, RL training is often unstable, with performance varying substantially across different model initializations and reward specifications, which undermines reproducibility. Negative findings from simulated treatment tasks indicate that naïve application of RL can yield unsafe or clinically irrelevant policies, particularly when validation is limited (79). Successful clinical translation is, therefore, contingent upon substantial methodological advances. This includes the development of high-fidelity patient models to serve as reliable simulators, the enforcement of safe-exploration constraints to prevent deleterious dose excursions, and the creation of transparent policy explanations for regulatory acceptance (80, 81). Addressing technical hurdles, such as sparse rewards and covariate shift between retrospective training data and prospective deployment, remains essential (82). These limitations indicate that current RL applications in oncology are largely experimental. However, as techniques such as model-based RL and offline RL mature in tandem with multi-omic monitoring and real-time digital-twin updating, RL may yet transform oncology treatment planning from empirical schedule selection to a continuous, data-driven control process optimized for each patient’s evolving biology and risk profile. The key applications, advantages, and limitations of Reinforcement Learning (RL) in precision oncology are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. A concise overview of the key Reinforcement Learning (RL) frameworks, their specific applications, advantages, limitations, and future directions in cancer treatment optimization.

| Application | RL Approach | Example/Description | Advantages | Limitations | Future Directions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy & Radiotherapy | Q-learning, Actor-Critic, Deep RL | Dose/schedule adjustment, beam-angle selection | Maintains tumor control, reduces planning time | Small cohorts, delayed rewards | Offline RL, safe exploration algorithms |

| Immunotherapy & Targeted Therapy | Model-free RL | Treatment initiation, duration, combination decisions | Potential for personalizing complex regimens | Model instability, lack of clinical validation | Digital twins updated with multi-omic data |

| Patient-Specific Digital Twins | Model-based RL | PK/PD simulations, tumor-immune eco-dynamic models | Enables safe testing in a virtual environment | Dependent on simulator accuracy | High-resolution digital twin + real-time data streaming |

| Multi-agent RL | Cooperative RL | Radiotherapy + systemic therapy combinations | Coordinates across combined modalities | Policy instability, data scarcity | Explainable multi-agent policies |

| General Challenges | - | - | - | Sample inefficiency, sparse rewards, covariate shift | Explainable RL, standardization |

7. Data modalities in precision oncology

The modern practice of precision oncology applies ML algorithms to extract clinically actionable signals from a growing spectrum of biomedical data. Several data modalities, including multi-omics, medical imaging & digital pathology, and EHRs, along with multi-modal integration, are required for precision oncology. High-throughput whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing (WGS/WES) have revealed millions of somatic variants per tumor, enabling ML classifiers to distinguish driver from passenger mutations and to prioritize therapeutic targets (83, 84). Deep neural networks have further improved the identification of mutational signatures associated with smoking, UV light, or defective DNA-repair pathways, and have begun to outperform traditional probabilistic approaches (85, 86). For transcriptomics, unsupervised clustering of RNA-seq profiles underpinned the molecular taxonomy used by TCGA; subsequent autoencoder and variational inference models generate latent factors that correlate more strongly with survival and therapy response than individual genes (37, 87). Epigenomic assays, such as DNA methylation arrays, have led to the development of RF and GBM classifiers that inform brain-tumor diagnostics (the “Heidelberg classifier”) and are increasingly being interpreted with explainable AI (88). True systems-level insight comes from integrating multiple layers of information. Network-based pipelines (INF, SNF) and factor-analysis frameworks (MOFA+) capture cross-omics correlations and consistently outperform single-layer models in prognostic tasks (89-91). Recent review of catalogue multi-omics algorithms, including Bayesian and transformer variants that incorporate pathway priors to improve biological plausibility (92).

Mass spectrometry proteomics now quantifies more than 10,000 proteins per tumor. ML feature-ranking pipelines have revealed panels that discriminate between high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma and benign tissue and predict survival (93). Targeted MS assays are moving toward clinical validation, supported by reviews detailing workflow standardization (94). DL frameworks, such as MS1Former, classify hepatocellular carcinoma spectra end-to-end and achieve pathology-level accuracy (95). Furthermore, metabolomics complements these data. RF and SVMs trained on plasma metabolites separate ER-positive from ER-negative breast cancers and anticipate therapeutic benefit in gastric cancer (96, 97). Spatial proteomics involves mapping proteins in a spatial context, which helps elucidate tumor heterogeneity (98, 99). Microfluidic imaging hybrids, combined with graph deep learning, delineate immune cell niches and identify perturbations that enhance T-cell infiltration (100, 101). DL has transformed cancer radiology with three-dimensional CNNs trained on National Lung Screening Trial data, achieving an AUC of greater than 94% for lung cancer prediction (102).

Meanwhile, a mammography model surpassed expert radiologists in breast cancer detection on two continents (103). Radiomics, the high-throughput extraction of texture, shape, and intensity features, links imaging phenotypes to genomics and outcomes, and is now reviewed as a pillar of personalized oncology (104). In digital pathology, CNNs trained on whole-slide images can classify non-small cell lung cancer subtypes with an AUC of approximately 0.97 and even infer actionable mutations directly from H&E slides (105). Weakly-supervised multiple-instance systems scale these capabilities to millions of slides, setting the stage for foundation models that jointly embed image tiles and text reports (106, 107). Spatially resolved assays extend conventional pathology by employing multiplex immunofluorescence (mIF) and spatial transcriptomics, which are analyzed with graph neural networks and attention mechanisms, to map cell–cell interactions that govern immune evasion and therapy resistance (108). Such spatial signatures already stratify response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer (109).

Structured EHR tables have long powered GBM and RF risk models, but transformer-based sequence models now capture complex, irregular patient trajectories and set new state-of-the-art benchmarks on multiple oncology prediction tasks (110). Natural-language-processing (NLP) systems based on BioBERT or GPT derivatives accurately extract stage, receptor status, and adverse events from pathology and follow-up notes, converting narrative text into ML-ready features (111). Privacy remains paramount. Systematic reviews document that federated learning improves generalizability across hospitals while complying with data-protection regulations, and that differential privacy (DP) noise can be added with only modest accuracy loss (112). Synthetic EHR generators provide an alternative approach, enabling open sharing when DP budgets are exhausted.

Further advancing the analysis of unstructured data, Large Language Models (LLMs), such as those powering GPT, have emerged as a transformative technology. While earlier NLP models, such as BioBERT, required task-specific fine-tuning, modern LLMs demonstrate zero-shot or few-shot capabilities, enabling them to perform complex tasks with minimal specialized training (113). In oncology, their applications are rapidly expanding. LLMs can efficiently extract structured information, such as cancer stage, treatment regimens, and genomic alterations, from unstructured pathology reports and clinical notes, reducing the manual workload on clinicians and researchers.

Beyond data extraction, LLMs are being explored for advanced clinical decision support. By synthesizing information from vast biomedical literature, clinical trial databases, and individual patient records, these models can help generate treatment recommendations for multidisciplinary tumor boards, often identifying a broader range of options than manual review alone (114-116). Furthermore, LLMs show promise in hypothesis generation by identifying novel patterns and drug combinations in the scientific literature, thereby accelerating discovery in cancer research. However, challenges such as the risk of generating factually incorrect information ("hallucinations"), ensuring data privacy, and addressing inherent biases must be addressed before their widespread and reliable integration into clinical practice (117, 118).

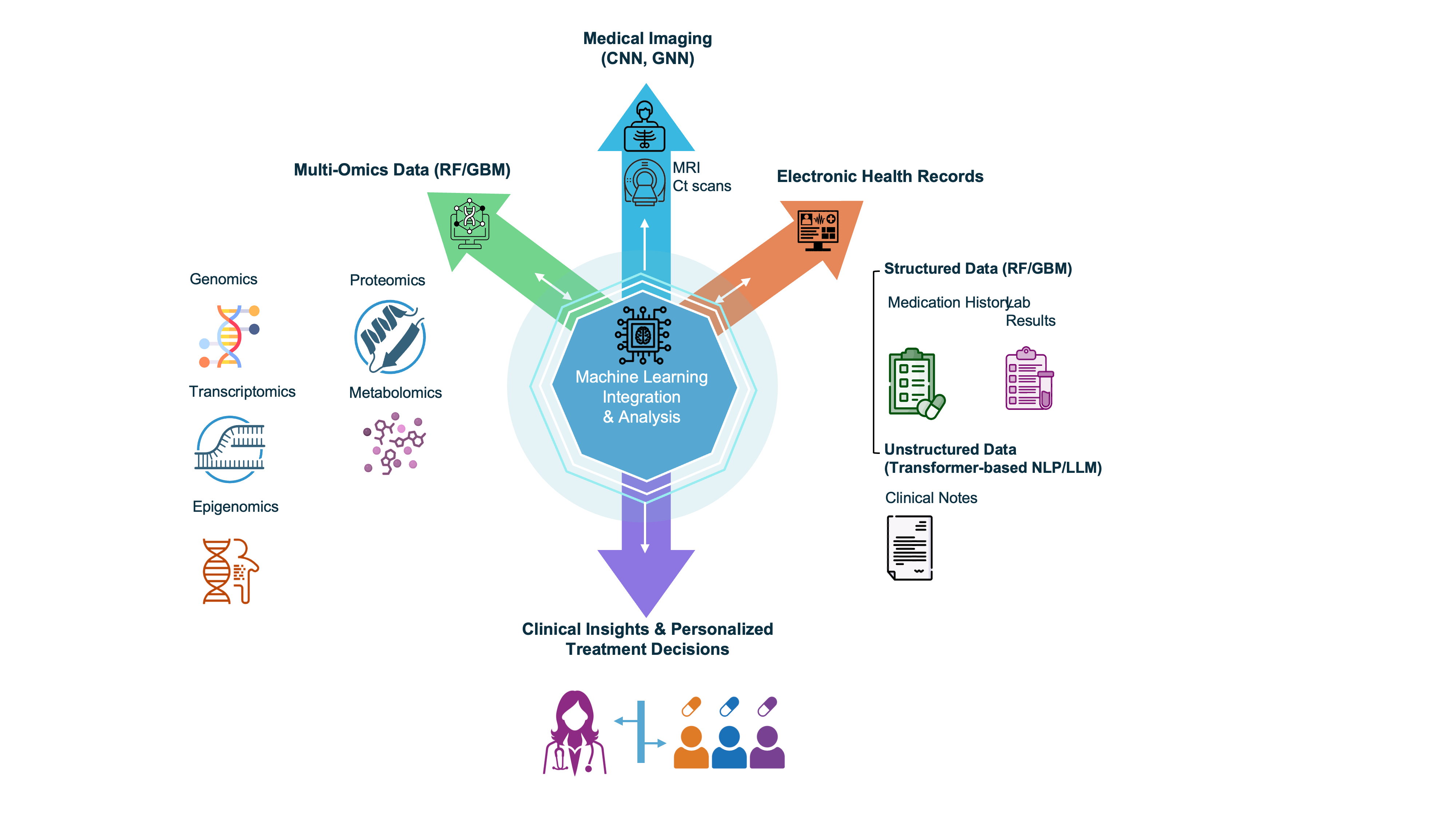

The integration of massive, heterogeneous biomedical datasets, encompassing continuous gene-expression profiles, sparse genetic variants, pixelated medical images, and unstructured clinical texts, remains an analytical challenge. These complexities are compounded by differing time stamps, missing data modalities, and pervasive batch effects, all of which render joint analysis far from trivial. Traditional early-fusion models address this by simply concatenating features, while late-fusion ensembles average predictions from modality-specific models. In contrast, intermediate-fusion strategies, such as transformer architectures that share attention heads but retain separate modality encoders, offer a balanced approach. Comparative surveys consistently show that these intermediate methods achieve the most favorable trade-off between accuracy and interpretability (92). Recent advances include the application of graph neural networks, which overlay molecular interaction networks onto patient-level data (119). Knowledge-guided Bayesian frameworks also contribute by encoding biological pathways as informative priors, thereby mitigating overfitting, particularly in studies with limited sample sizes. Meanwhile, foundation models, pretrained on millions of images and billions of textual data points, such as MUSK, BiomedCLIP, and HONeYBEE, demonstrate robust cross-modality and cross-task generalization, leading to improved performance in applications ranging from lung cancer screening to automated pathology report generation (107, 120, 121). A notable example of clinical impact is the use of MRI-based digital twins, which integrate imaging data, genomic information, and treatment parameters to enhance patient care. These models have achieved approximately a 10% improvement in predicting pathological complete response in triple-negative breast cancer, compared to radiomics-based approaches alone (109). In parallel, conceptual and regulatory frameworks for these so-called “living models” are rapidly emerging to support their clinical translation (8). Nonetheless, persistent obstacles remain, including: (i) robust imputation strategies for systematically missing modalities; (ii) harmonization of data acquisition protocols; (iii) the development of standardized explainability metrics across heterogeneous data types; and (iv) ensuring equitable model performance across diverse ancestries and healthcare environments (122-126). Community-driven initiatives, such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), The Cancer Imaging Archive, and pan-European FAIR data projects, are progressively addressing these challenges (127-131). Collectively, these efforts are expected to accelerate the clinical adoption of trustworthy, multi-modal ML systems in oncology. Figure 4 illustrates the core data modalities used in precision oncology and the ML models applied to each. The integration of heterogeneous biomedical datasets underpins ML-driven clinical innovation.

The following section examines how these methodological advances are being applied in clinical oncology settings to optimize treatment, personalize immunotherapy, and develop patient-specific digital twins.

Figure 4. Core data modalities and their corresponding ML methods in precision oncology. Multi-omics data, including genomics and proteomics, are analyzed using models such as RFs and GBMs to identify biomarkers and disease mechanisms. Medical Imaging and Radiomics, encompassing CT/MRI scans and digital pathology slides, are primarily processed by CNNs for tasks like tumor characterization and diagnostic classification. Electronic Health Records (EHRs) use RF/GBM for structured data analysis (e.g., laboratory results). In contrast, Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Large Language Models (LLMs) are used to extract and interpret information from unstructured clinical notes. By integrating these diverse data streams and their specific analytical models, a patient profile is generated to guide personalized treatment decisions.

8. Applications of machine learning in clinical oncology

Building upon the preceding discussion of data modalities and computational frameworks, this section shifts from methodological foundations to the translational applications of ML in oncology. Here, we examine how diverse ML algorithms are being synthesized and applied to address high-impact clinical challenges across three domains: (i) the optimization of conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy, focusing on treatment planning and response stratification; (ii) the personalization of immunotherapy and targeted therapy, where models guide patient selection and predict therapeutic efficacy; and (iii) the development of patient-specific digital twins, which integrate multimodal data to simulate disease progression and forecast treatment outcomes. Together, these domains exemplify the practical translation of computational models into decision-support tools that enable personalized cancer care.

ML has markedly enhanced the personalization of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Predictive models that integrate genomics, imaging, and clinical data now accurately estimate patient-specific treatment responses and toxicities, enabling more precise dose and schedule optimization. Beyond methodological progress, several clinically oriented ML applications have demonstrated clear translational potential. For example, deep learning models that predict Pareto-optimal dose distributions for intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) have enabled individualized planning in prostate cancer cohorts (132). Similarly, learning-based beam-angle selection systems have achieved tumor coverage and organ-at-risk sparing comparable to those of expert-generated plans in thoracic IMRT (133). Moreover, reinforcement learning frameworks have been successfully applied to optimize fractionation schedules in lung cancer radiotherapy (72) and to design adaptive chemotherapy regimens tailored to patient variability (70). These developments underscore how ML, particularly deep and reinforcement learning, is evolving from theoretical optimization toward clinically deployable tools for precision chemoradiotherapy.

ML is also transforming patient stratification and treatment personalization in immunotherapy and targeted therapy, key pillars of modern precision oncology. Several AI-based deep-learning frameworks have now demonstrated clinical validity. For instance, an automated model for PD-L1 immunohistochemistry scoring in lung cancer exhibited high concordance with pathologist assessments (134). In skin cutaneous melanoma, ML-derived immune-cell-related gene signatures have been shown to predict both prognosis and response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (135). Additionally, radiomics-based ML pipelines achieved high predictive performance (AUCs) in forecasting immunotherapy outcomes for inoperable advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (136). Furthermore, in EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma, integrative deep-learning models that combine CT imaging, histopathology, and clinical data successfully predict sensitivity to HER-targeted therapies (137). Together, these translational studies demonstrate that ML is moving decisively beyond proof-of-concept research toward real-world clinical implementation in immunotherapy and targeted therapy.

Patient-specific digital twins are rapidly maturing from conceptual frameworks into translational tools that integrate longitudinal imaging, molecular profiles, and clinical data to simulate individualized tumor dynamics and test treatment strategies in silico. Recent imaging-guided efforts have shown that calibrating mechanistic tumor growth models with serial quantitative MRI enables accurate, patient-level prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer cohorts, demonstrating clear translational potential (138). Complementing these developments, recent studies have shown the feasibility of digital twin–based diagnostic frameworks for early cancer detection. For instance, an automated cervical cancer detection digital twin, developed using the SIPaKMeD dataset, has shown how virtual patient models can be integrated with ML to enhance diagnostic precision and workflow efficiency. In this system, the proposed CervixNet classifier used RNNs to extract 1,172 imaging features, followed by PCA to reduce dimensionality to 792 key features, achieving 98.91% classification accuracy across all cervical cell classes, particularly when using an SVM (139). This framework highlights how digital twins can bridge the gap between patients, clinicians, and computational models within a scalable, intelligent healthcare ecosystem, underscoring their broader potential in oncology diagnostics and treatment planning. Robust digital-twin construction requires multimodal data fusion, uncertainty quantification, and frequent synchronization with incoming clinical measurements to support safe decision-making and prospective evaluation. Methodological advances that couple fast, reduced-order mechanistic models with machine-learning surrogates enable rapid, spatially resolved simulations suitable for clinical workflows. At the same time, early clinical-translation reports illustrate how digital twins can be used to (i) prioritize individual treatment regimens, (ii) forecast the likelihood of pathological complete response, and (iii) run virtual trials of adaptive dosing or sequencing strategies before patient exposure (140). Despite their early developmental stage, emerging evidence suggests that well-validated, transparent, and clinician-guided digital twins have the potential to evolve into robust platforms for personalized therapy optimization and adaptive trial design in oncology.

9. Regulatory, economic, and implementation considerations

In the United States, most oncology AI tools are regulated as Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) or “device software functions” by the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (141). The agency adopts a total product lifecycle approach. It primarily clears AI tools through the 510(k) pathway when a predicate device exists; novel tools may proceed via De Novo, whereas relatively few require PMA. In 2024–2025, the FDA finalized guidance on Predetermined Change Control Plans (PCCPs) for AI-enabled devices, enabling manufacturers to pre-specify data, validation methods, and guardrails for future model updates while maintaining safety and effectiveness (142). The FDA also endorses Good Machine Learning Practice (GMLP) principles for data quality, model development, transparency, and post-market monitoring (143). Together, these documents define expectations for clinical evidence, human oversight, real-world performance monitoring, and controlled updates of learning systems. The EU AI Act entered into force on 1 August 2024. Medical AI used as (or within) medical devices is generally classified as high-risk, which triggers obligations for providers and deployers, including risk management, data governance, technical documentation, logging, transparency/human-oversight measures, robustness, and post-market monitoring (144-146). Several products have already been authorized, including AI tools for breast cancer screening (ProFound AI, Transpara), real-time colorectal polyp detection (GI Genius), prostate pathology (Paige Prostate, Ibex Galen), prostate MRI interpretation (Quantib Prostate), and lung nodule malignancy assessment (Optellum).

Beyond regulatory approval, economic and implementation factors need to be considered. The introduction of AI entails costs for licensing, integration, storage, and maintenance; however, it may yield savings by improving diagnostic efficiency and enabling earlier cancer detection. For instance, a recent cost-effectiveness simulation suggests that adding an AI-based system to low-dose CT lung cancer screening is both less costly and more effective, demonstrating a favorable economic profile (147). Similarly, in pathology, AI has reduced diagnostic time; for example, the Paige Prostate system enabled pathologists to reduce slide reviews from 579 to approximately 200, cutting diagnosis time from around 15.8 hours to 6.8 hours (a ~65% reduction).

The effect of AI on physician workload is nuanced. In one analysis of AI-driven imaging workflows, more than 85% of studies projected that AI would increase workload, primarily due to increased post-processing and interpretation demands (148, 149). Infrastructure requirements also pose challenges: clinical deployment of AI in imaging typically demands vendor-neutral, future-proof platforms with secure architectures, high-performance computing, and integration with PACS, EHR, and IT systems (150). These factors indicate that the successful translation of oncology AI hinges not only on technical performance but also on a cost-effective roadmap, workforce impact, and institutional readiness.

Discussion

The integration of ML into clinical oncology holds immense promise, but its successful translation from research to routine practice requires overcoming systemic challenges that extend beyond algorithmic performance. The foundation of any model is its data, and here, hurdles persist. Key among them is data heterogeneity, in which models trained on uniform data from a single institution often fail to generalize across diverse patient ancestries and varied data acquisition protocols (151). This issue is compounded by class imbalance, especially for rare cancers or mutational subtypes, which can bias model performance (152). Future progress will depend on developing robust data harmonization techniques and federated learning frameworks that enable training on multi-institutional data without compromising patient privacy (153, 154). Furthermore, research on synthetic data generation using GANs or diffusion models offers a promising avenue for augmenting training cohorts and mitigating data scarcity.

Beyond the data itself, the models pose barriers to adoption. The "black box" nature of many DL algorithms impedes interpretability, a factor that undermines clinician trust and complicates regulatory scrutiny. There is also a risk of algorithmic bias, where models perpetuate or even amplify historical inequities present in training data, leading to inequitable performance across demographic groups. To address these issues, the field must prioritize explainable AI (XAI), including the development of inherently interpretable models and the rigorous validation of post-hoc explanation methods (155, 156). To combat bias, systematic algorithmic auditing across diverse, multi-center datasets must become standard practice before clinical deployment (157).

Finally, even a technically robust and fair model is clinically useful only if it can be integrated into existing healthcare ecosystems. Hurdles include a lack of interoperability between ML platforms and hospital information systems, as well as the need for clear regulatory and ethical frameworks to govern the use of AI as a medical device (158). The substantial computational cost and requirement for specialized infrastructure can also limit adoption. Therefore, future success hinges on closer collaboration among data scientists, clinicians, ethicists, and policymakers to build interoperable digital health ecosystems that support continuous learning and improvement. Ultimately, the path to widespread adoption requires rigorous prospective multicenter trials that demonstrate not only algorithmic accuracy but also tangible clinical utility and patient benefit, which are necessary to secure clinician trust and regulatory approval.

ML techniques have rapidly matured from exploratory classifiers applied to small gene-expression matrices into a robust, multi-modal ecosystem that now informs every stage of the oncology care continuum. Contemporary supervised, unsupervised, deep-learning, and reinforcement-learning frameworks routinely achieve expert-level accuracy in tumor detection, molecular sub-typing, prognosis, and treatment-response prediction, while emerging graph and transformer architectures are beginning to uncover higher-order biological interactions and to power digital-twin simulations of individual patients (3, 8, 56, 76, 107). The concurrent evolution of privacy-preserving data-centric strategies, federated learning, differential privacy, and synthetic-data generation, together with the growth of international consortia (e.g., TCGA, AACR Project GENIE), has expanded both the diversity and quality of training corpora, thereby improving generalizability across ancestries, institutions, and acquisition platforms (17, 89, 112). As a result, ML-enabled precision oncology has progressed from proof-of-concept demonstrations into validated clinical decision-support tools that can stratify risk more finely than traditional staging systems, standardize biomarker assessment, and suggest adaptive therapy schedules likely to improve both survival and quality of life (29, 35, 69, 75).

Nevertheless, the field now stands at an inflection point where technical performance must translate into trustworthy, equitable, and scalable clinical deployment. Key priorities include: (i) rigorous, prospective multi-center trials and post-marketing surveillance to ensure external validity; (ii) harmonized reporting standards and explainable-AI frameworks that expose model logic to clinicians, regulators and patients (15); (iii) systematic mitigation of algorithmic bias so that benefits accrue across demographic groups and resource-constrained settings (33).; and (iv) integration of ML outputs into interoperable electronic-health-record and imaging infrastructures that support continuous learning and clinician feedback loops (19). Addressing these challenges will require closer collaboration among data scientists, biologists, clinicians, ethicists, and policymakers, as well as sustained investment in open, FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data resources. If these hurdles are met, next-generation ML, anchored by foundation models capable of reasoning across images, omics, and free text, will be poised to deliver truly personalized, dynamically adaptive oncology that maximizes therapeutic efficacy while minimizing harm, fulfilling the long-promised vision of precision cancer medicine (107, 120, 121).

References

1. Cell editorial team. Five decades of advances in cancer research. Cell. 2024;187(7):1567-1568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.02.044

2. Re A, Nardella C, Quattrone A, Lunardi A. Editorial: precision medicine in oncology. Front Oncol. 2018;8:479. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2018.00479

3. Fountzilas E, Pearce T, Baysal MA, Chakraborty A, Tsimberidou AM. Convergence of evolving artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques in precision oncology. NPJ Digit Med. 2025;8(1):75. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01471-y

4. Repetto M, Fernandez N, Drilon A, Chakravarty D. Precision oncology: 2024 in review. Cancer Discov. 2024;14(12):2332-2345. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-24-1476

5. El Naqa I. Perspectives on making big data analytics work for oncology. Methods. 2016;111:32-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.08.010

6. Loni M, Poursalim F, Asadi M, Gharehbaghi A. A review on generative AI models for synthetic medical text, time series, and longitudinal data. NPJ Digit Med. 2025;8(1):281. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01409-w

7. Li C, Guo Y, Lin X, Feng X, Xu D, Yang R. Deep reinforcement learning in radiation therapy planning optimization: a comprehensive review. Phys Med. 2024;125:104498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmp.2024.104498

8. Giansanti D, Morelli S. Exploring the potential of digital twins in cancer treatment: a narrative review of reviews. J Clin Med. 2025;14(10):3574. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103574

9. Chang YW, Ryu JK, An JK, Choi N, Park YM, Ko KH, et al. Artificial intelligence for breast cancer screening in mammography (AI-STREAM): preliminary analysis of a prospective multicenter cohort study. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):2248. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57469-3

10. He Y, Zhao H, Wong STC. Deep learning powers cancer diagnosis in digital pathology. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2021;88:101820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compmedimag.2020.101820

11. Hashem H, Sultan I. Revolutionizing precision oncology: the role of artificial intelligence in personalized pediatric cancer care. Front Med (Lausanne). 2025;12:1555893. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2025.1555893

12. Shah K, Ahmed M, Kazi JU. The aurora kinase/beta-catenin axis contributes to dexamethasone resistance in leukemia. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2021;5(1):13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-021-00148-5

13. Nasimian A, Ahmed M, Hedenfalk I, Kazi JU. A deep tabular data learning model predicting cisplatin sensitivity identifies BCL2L1 dependency in cancer. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2023;21:956-964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2023.01.020

14. Nasimian A, Al Ashiri L, Ahmed M, Duan H, Zhang X, Ronnstrand L, Kazi JU. A receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor sensitivity prediction model identifies AXL dependency in leukemia. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):3830. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24043830

15. Abgrall G, Holder AL, Chelly Dagdia Z, Zeitouni K, Monnet X. Should AI models be explainable to clinicians? Crit Care. 2024;28(1):301. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-024-05005-y

16. Golub TR, Slonim DK, Tamayo P, Huard C, Gaasenbeek M, Mesirov JP, et al. Molecular classification of cancer: class discovery and class prediction by gene expression monitoring. Science. 1999;286(5439):531-537. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.286.5439.531

17. Consortium APG. AACR project GENIE: powering precision medicine through an international consortium. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(8):818-831. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0151

18. Samuel GN, Farsides B. The UK's 100,000 genomes project: manifesting policymakers' expectations. New Genet Soc. 2017;36(4):336-353. https://doi.org/10.1080/14636778.2017.1370671

19. Mandl KD, Gottlieb D, Mandel JC. Integration of AI in healthcare requires an interoperable digital data ecosystem. Nat Med. 2024;30(3):631-634. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02783-w

20. Rafique R, Islam SMR, Kazi JU. Machine learning in the prediction of cancer therapy. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:4003-4017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2021.07.003

21. Kazi JU. AI-driven drug response prediction for personalized cancer medicine. In: artificial intelligence for disease diagnosis and prognosis in smart healthcare. 1st ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2023. p. 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003251903-4

22. Shah K, Nasimian A, Ahmed M, Al Ashiri L, Denison L, Sime W, et al. PLK1 as a cooperating partner for BCL2-mediated antiapoptotic program in leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 2023;13(1):139. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-023-00914-7

23. Nasimian A, Younus S, Tatli O, Hammarlund EU, Pienta KJ, Ronnstrand L, et al. AlphaML: a clear, legible, explainable, transparent, and elucidative binary classification platform for tabular data. Patterns (N Y). 2024;5(1):100897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2023.100897

24. Huang S, Cai N, Pacheco PP, Narrandes S, Wang Y, Xu W. Applications of support vector machine (SVM) learning in cancer genomics. Cancer Genom. Proteom. 2018;15(1):41-51. https://doi.org/10.21873/cgp.20063

25. Segal NH, Pavlidis P, Noble WS, Antonescu CR, Viale A, Wesley UV, et al. Classification of clear-cell sarcoma as a subtype of melanoma by genomic profiling. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(9):1775-1781. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.10.108

26. Diaz-Uriarte R, Alvarez de Andres S. Gene selection and classification of microarray data using random forest. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-7-3

27. Li G, Xia K. Enhanced prognostic prediction of cancer-specific mortality in elderly bladder cancer patients post-radical cystectomy: an XGBoost model study. Transl Cancer Res. 2025;14(3):1902-1914. https://doi.org/10.21037/tcr-24-2023

28. Salvi M, Molinari F, Acharya UR, Molinaro L, Meiburger KM. Impact of stain normalization and patch selection on the performance of convolutional neural networks in histological breast and prostate cancer classification. Comput Methods Programs Biomed Update. 2021;1:100004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpbup.2021.100004

29. Akbarnejad A, Ray N, Barnes PJ, Bigras G. Toward accurate deep learning-based prediction of ki67, ER, PR, and HER2 status from H&E-stained breast cancer images. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2025;33(3):131-141. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAI.0000000000001258

30. Plass M, Olteanu GE, Dacic S, Kern I, Zacharias M, Popper H, et al. Comparative performance of PD-L1 scoring by pathologists and AI algorithms. Histopathology. 2025;87(1):90-100. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.15432

31. Piffer S, Ubaldi L, Tangaro S, Retico A, Talamonti C. Tackling the small data problem in medical image classification with artificial intelligence: a systematic review. Prog Biomed Eng (Bristol). 2024;6(3):032001. https://doi.org/10.1088/2516-1091/ad525b

32. Adeoye J, Hui L, Su YX. Data-centric artificial intelligence in oncology: a systematic review assessing data quality in machine learning models for head and neck cancer. J Big Data. 2023;10(1):28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-023-00703-w

33. Tasci E, Zhuge Y, Camphausen K, Krauze AV. Bias and class imbalance in oncologic data-towards inclusive and transferrable AI in large scale oncology data sets. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(12):2897. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14122897

34. Bi WL, Hosny A, Schabath MB, Giger ML, Birkbak NJ, Mehrtash A, et al. Artificial intelligence in cancer imaging: clinical challenges and applications. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(2):127-157. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21552

35. Rakaee M, Tafavvoghi M, Ricciuti B, Alessi JV, Cortellini A, Citarella F, et al. Deep learning model for predicting immunotherapy response in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2025;11(2):109-118. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2024.5356

36. Prat A, Perou CM. Deconstructing the molecular portraits of breast cancer. Mol Oncol. 2011;5(1):5-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molonc.2010.11.003

37. Zhang H, Xiong X, Cheng M, Ji L, Ning K. Deep learning enabled integration of tumor microenvironment microbial profiles and host gene expressions for interpretable survival subtyping in diverse types of cancers. mSystems. 2024;9(12):e0139524. https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.01395-24

38. Zhai Z, Lei YL, Wang R, Xie Y. Supervised capacity preserving mapping: a clustering guided visualization method for scRNA-seq data. Bioinformatics. 2022;38(9):2496-2503. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btac131

39. Madhumita, Paul S. Capturing the latent space of an autoencoder for multi-omics integration and cancer subtyping. Comput Biol Med. 2022;148:105832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105832

40. Xu H, Fu H, Long Y, Ang KS, Sethi R, Chong K, et al. Unsupervised spatially embedded deep representation of spatial transcriptomics. Genome Med. 2024;16(1):12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-024-01283-x

41. Jiménez-Gaona Y, Carrión-Figueroa D, Lakshminarayanan V, Rodríguez-Álvarez MJ. Gan-based data augmentation to improve breast ultrasound and mammography mass classification. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control. 2024;94:106255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2024.106255

42. Skandarani Y, Jodoin PM, Lalande A. GANs for medical image synthesis: an empirical study. J Imaging. 2023;9(3):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging9030069

43. Qiu J, Hu Y, Li L, Erzurumluoglu AM, Braenne I, Whitehurst C, et al. Deep representation learning for clustering longitudinal survival data from electronic health records. Nat Commun. 2025;16:2534. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56625-z

44. Sonmez TF, Harvey DJ, Beckett LA; Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. An unsupervised learning approach for clustering joint trajectories of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers: an application to ADNI data. Alzheimers Dement. 2025;21(2):e14524. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.14524

45. Moassefi M, Rouzrokh P, Conte GM, Vahdati S, Fu T, Tahmasebi A, et al. Reproducibility of deep learning algorithms developed for medical imaging analysis: a systematic review. J Digit Imaging. 2023;36(5):2306-2312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10278-023-00870-5

46. Janizek JD, Spiro A, Celik S, Blue BW, Russell JC, Lee TI, et al. PAUSE: principled feature attribution for unsupervised gene expression analysis. Genome Biology. 2023;24(1):81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-023-02901-4

47. Unger M, Kather JN. A systematic analysis of deep learning in genomics and histopathology for precision oncology. BMC Med Genomics. 2024;17(1):48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-024-01796-9

48. Chowa SS, Azam S, Montaha S, Payel IJ, Bhuiyan MRI, Hasan MZ, et al. Graph neural network-based breast cancer diagnosis using ultrasound images with optimized graph construction integrating the medically significant features. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149(20):18039-18064. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-023-05464-w

49. Vaida M, Wu J, Himdiat E, Haince JF, Bux RA, Huang G, et al. M-GNN: a graph neural network framework for lung cancer detection using metabolomics and heterogeneous graph modeling. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(10):4655. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26104655

50. Jia H, Zhang J, Ma K, Qiao X, Ren L, Shi X. Application of convolutional neural networks in medical images: a bibliometric analysis. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2024;14(5):3501-3518. https://doi.org/10.21037/qims-23-1600

51. Chen C, Mat Isa NA, Liu X. A review of convolutional neural network based methods for medical image classification. Comput Biol Med. 2025;185:109507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.109507

52. Jiao F, Shang Z, Lu H, Chen P, Chen S, Xiao J, et al. A weakly supervised deep learning framework for automated PD-L1 expression analysis in lung cancer. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1540087. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1540087

53. Shamai G, Livne A, Polonia A, Sabo E, Cretu A, Bar-Sela G, et al. Deep learning-based image analysis predicts PD-L1 status from H&E-stained histopathology images in breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):6753. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34275-9

54. Qu Z, Wang Y, Guo D, He G, Sui C, Duan Y, et al. Comparison of deep learning models to traditional Cox regression in predicting survival of colon cancer: based on the SEER database. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;39(9):1816–1826. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.16598

55. Chae S, Street WN, Ramaraju N, Gilbertson-White S. Prediction of cancer symptom trajectory using longitudinal electronic health record data and long short-term memory neural network. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2024;8:e2300039. https://doi.org/10.1200/CCI.23.00039

56. Jiang X, Wang S, Zhang Y. Vision transformer promotes cancer diagnosis: a comprehensive review. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;252:124113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2024.124113

57. Reddy CKK, Reddy PA, Janapati H, Assiri B, Shuaib M, Alam S, et al. A fine-tuned vision transformer based enhanced multi-class brain tumor classification using MRI scan imagery. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1400341. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2024.1400341

58. Dalla-Torre H, Gonzalez L, Mendoza-Revilla J, Lopez Carranza N, Grzywaczewski AH, Oteri F, et al. Nucleotide transformer: building and evaluating robust foundation models for human genomics. Nat Methods. 2025;22(2):287-297. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-024-02523-z

59. Wang C, Kumar GA, Rajapakse JC. Drug discovery and mechanism prediction with explainable graph neural networks. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):179. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83090-3

60. Campana PA, Prasse P, Lienhard M, Thedinga K, Herwig R, Scheffer T. Cancer drug sensitivity estimation using modular deep graph neural networks. NAR Genom Bioinform. 2024;6(2):lqae043. https://doi.org/10.1093/nargab/lqae043

61. Schulte-Sasse R, Budach S, Hnisz D, Marsico A. Integration of multiomics data with graph convolutional networks to identify new cancer genes and their associated molecular mechanisms. Nat Mach Intell. 2021;3(6):513-526. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-021-00325-y

62. Su X, Hu P, Li D, Zhao B, Niu Z, Herget T, et al. Interpretable identification of cancer genes across biological networks via transformer-powered graph representation learning. Nat Biomed Eng. 2025;9(3):371-389. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-024-01312-5

63. Zhang J, Chao H, Dasegowda G, Wang G, Kalra MK, Yan P. Revisiting the trustworthiness of saliency methods in radiology AI. Radiology: Artificial Intelligence. 2024;6(1):e220221. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryai.220221

64. Sarkar S, Bora RP, Kaushal B, George SN, Raja K. Assessing the noise robustness of class activation maps: a framework for reliable model interpretability. Image and Vision Computing. 2025;163:105717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imavis.2025.105717

65. Brima Y, Atemkeng M. Saliency-driven explainable deep learning in medical imaging: bridging visual explainability and statistical quantitative analysis. Biodata Min. 2024;17(1):18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13040-024-00370-4

66. Anjana MP, Arun KS, Madhavan M. Transformer-based models for uncovering genetic mutations in cancerous and non-cancerous genomes. Gene. 2025;963:149460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2025.149460

67. Moglia V, Johnson O, Cook G, de Kamps M, Smith L. Artificial intelligence methods applied to longitudinal data from electronic health records for prediction of cancer: a scoping review. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2025;25(1):24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-025-02473-w

68. Jayaraman P, Desman J, Sabounchi M, Nadkarni GN, Sakhuja A. A primer on reinforcement learning in medicine for clinicians. NPJ Digit Med. 2024;7(1):337. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01316-0

69. Banumathi K, Venkatesan L, Benjamin LS, Vijayalakshmi K, Satchi NS. Reinforcement learning in personalized medicine: a comprehensive review of treatment optimization strategies. Cureus. 2025;17(4):e82756. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.82756

70. Eastman B, Przedborski M, Kohandel M. Reinforcement learning derived chemotherapeutic schedules for robust patient-specific therapy. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):17882. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97028-6

71. Tosca EM, De Carlo A, Ronchi D, Magni P. Model-informed reinforcement learning for enabling precision dosing via adaptive dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2024;116(3):619-636. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.3356

72. Tseng HH, Luo Y, Cui S, Chien JT, Ten Haken RK, El Naqa I. Deep reinforcement learning for automated radiation adaptation in lung cancer. Med Phys. 2017;44(12):6690-6705. https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.12625

73. Mashayekhi H, Nazari M, Jafarinejad F, Meskin N. Deep reinforcement learning-based control of chemo-drug dose in cancer treatment. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2024;243:107884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2023.107884

74. Lu Y, Chu Q, Li Z, Wang M, Gatenby R, Zhang Q. Deep reinforcement learning identifies personalized intermittent androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Brief Bioinform. 2024;25(2):bbae071. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbae071

75. Gallagher K, Strobl MAR, Park DS, Spoendlin FC, Gatenby RA, Maini PK, et al. Mathematical model-driven deep learning enables personalized adaptive therapy. Cancer Res. 2024;84(11):1929-1941. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-23-2040

76. De Domenico M, Allegri L, Caldarelli G, d'Andrea V, Di Camillo B, Rocha LM, et al. Challenges and opportunities for digital twins in precision medicine from a complex systems perspective. NPJ Digit Med. 2025;8(1):37. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01402-3

77. Campos de Freitas J, Cantane DR, Rocha H, Dias J. A multiobjective beam angle optimization framework for intensity‑modulated radiation therapy. Eur J Oper Res. 2024;318(1):286-296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2024.05.004

78. Teplytska O, Ernst M, Koltermann LM, Valderrama D, Trunz E, Vaisband M, et al. Machine learning methods for precision dosing in anticancer drug therapy: a scoping review. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2024 Sep;63(9):1221-1237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-024-01409-9

79. Chemingui Y, Deshwal A, Wei H, Fern A, Doppa J. Constraint-adaptive policy switching for offline safe reinforcement learning. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2025;39(15):15722-15730. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v39i15.33726

80. Bozcuk HS, Artac M. A simulated trial with reinforcement learning for the efficacy of irinotecan and ifosfamide versus topotecan in relapsed, extensive stage small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2024;24(1):1207. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-12985-1

81. Liu S, See KC, Ngiam KY, Celi LA, Sun X, Feng M. Reinforcement learning for clinical decision support in critical care: comprehensive review. J Med Internet Res 2020;22(7):e18477. https://doi.org/10.2196/18477

82. Hickman X, Lu Y, Prince D. Hybrid safe reinforcement learning: tackling distribution shift and outliers with the student-t’s process. Neurocomputing. 2025;634:129912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2025.129912

83. Andrades R, Recamonde-Mendoza M. Machine learning methods for prediction of cancer driver genes: a survey paper. Brief Bioinform. 2022;23(3):bbac062. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbac062

84. Ostroverkhova D, Przytycka TM, Panchenko AR. Cancer driver mutations: predictions and reality. Trends Mol Med. 2023;29(7):554-566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2023.03.007

85. Vilov S, Heinig M. Deepsom: a CNN-based approach to somatic variant calling in WGS samples without a matched normal. Bioinformatics. 2023;39(1):btac828. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btac828

86. Yaacov A, Ben Cohen G, Landau J, Hope T, Simon I, Rosenberg S. Cancer mutational signatures identification in clinical assays using neural embedding-based representations. Cell Rep Med. 2024;5(6):101608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101608

87. Argelaguet R, Velten B, Arnol D, Dietrich S, Zenz T, Marioni JC, et al. Multi‐omics factor analysis-a framework for unsupervised integration of multi‐omics data sets. Mol Syst Biol. 2018;14(6):e8124. https://doi.org/10.15252/msb.20178124

88. Benfatto S, Sill M, Jones DTW, Pfister SM, Sahm F, von Deimling A, et al. Explainable artificial intelligence of DNA methylation-based brain tumor diagnostics. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):1787. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57078-0

89. Jia C, Wang T, Cui D, Tian Y, Liu G, Xu Z, et al. A metagene based similarity network fusion approach for multi-omics data integration identified novel subtypes in renal cell carcinoma. Brief Bioinform. 2024;25(6):bbae606. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbae606

90. Chierici M, Bussola N, Marcolini A, Francescatto M, Zandonà A, Trastulla L, et al. Integrative Network Fusion: a Multi-Omics Approach in Molecular Profiling. Frontiers in Oncology. 2020;10:2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.01065

91. Demir Karaman E, Isik Z. Multi-omics data analysis identifies prognostic biomarkers across cancers. Med Sci (Basel). 2023;11(3):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci11030044

92. Baiao AR, Cai Z, Poulos RC, Robinson PJ, Reddel RR, Zhong Q, et al. A technical review of multi-omics data integration methods: from classical statistical to deep generative approaches. Brief Bioinform. 2025;26(4):bbaf355. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbaf355

93. De Silva S, Alli-Shaik A, Gunaratne J. Machine learning-enhanced extraction of biomarkers for high-grade serous ovarian cancer from proteomics data. Sci Data. 2024;11(1):685. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03536-1

94. Wenk D, Zuo C, Kislinger T, Sepiashvili L. Recent developments in mass-spectrometry-based targeted proteomics of clinical cancer biomarkers. Clin Proteomics. 2024;21(1):6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12014-024-09452-1

95. Xu W, Zhang L, Qian X, Sun N, Tu X, Zhou D, et al. A deep learning framework for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis using MS1 data. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):26705. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77494-4

96. Arumalla KK, Haince JF, Bux RA, Huang G, Tappia PS, Ramjiawan B, et al. Metabolomics-based machine learning models accurately predict breast cancer estrogen receptor status. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(23):13029. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms252313029

97. Chen Y, Wang B, Zhao Y, Shao X, Wang M, Ma F, et al. Metabolomic machine learning predictor for diagnosis and prognosis of gastric cancer. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):1657. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46043-y

98. Xu Y, Wang X, Li Y, Mao Y, Su Y, Mao Y, et al. Multimodal single cell-resolved spatial proteomics reveal pancreatic tumor heterogeneity. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):10100. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54438-0

99. Bungaro C, Guida M, Apollonio B. Spatial proteomics of the tumor microenvironment in melanoma: current insights and future directions. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1568456. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1568456

100. Jing SY, Wang HQ, Lin P, Yuan J, Tang ZX, Li H. Quantifying and interpreting biologically meaningful spatial signatures within tumor microenvironments. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2025;9(1):68. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-00857-1