REVIEW ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS

CRISPR in the Tumor Microenvironment: From Diagnostic Profiling to Precision Therapy

Lirenhui Zhou1*, Meiya Mu1*, Meihua Yang1*, Xiaojing Liu1*, Guangrong Zou2#, Chaoxing Liu3#

Received 2025 Sept 8

Accepted 2025 Oct 14

Epub ahead of print: December 2025

Published in issue 2026 Feb 15

Correspondence: Chaoxing Liu - Email: liuchx69@mail.sysu.edu.cn

Guangrong Zou - Email: zougr3@mail.sysu.edu.cn

The author’s information is available at the end of the article.

© 2026 The Author(s). Published by GCINC Press. Open Access licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. To view a copy: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a dynamic and heterogeneous ecosystem that shapes tumor initiation, progression, immune evasion, and therapeutic resistance. Its cellular and molecular composition evolves throughout disease progression. The CRISPR–Cas gene-editing system has emerged as a transformative platform for decoding TME biology and enabling innovative diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. In this review, we outline the fundamental principles of CRISPR–Cas technologies and summarize their applications in functional genetic screening, interrogation of cell–cell interactions, and dissection of dynamic signaling networks within the TME. We highlight advances in CRISPR-based diagnostic platforms that allow highly sensitive and specific detection of cancer-associated signals across in vitro systems, patient-derived organoids, and ex vivo tumor samples. Furthermore, we discuss emerging CRISPR-enabled therapeutic approaches targeting the TME, including genetic modulation of tumor cells, reprogramming of immune and stromal compartments, and disruption of tumor vasculature and metabolic niches to enhance antitumor efficacy. Particular emphasis is placed on delivery strategies that achieve cell-type specificity and spatial precision. Finally, we examine key challenges that limit clinical translation, such as off-target editing, immunogenicity, and the inherent plasticity and heterogeneity of the TME, and discuss future directions to improve safety, robustness, and therapeutic durability. Collectively, this review provides a comprehensive framework for leveraging CRISPR–Cas technologies to advance TME-focused cancer diagnostics and therapeutics.

Keywords: Biomarkers, CRISPR-Cas, Tumor microenvironment, Drug resistance, Gene editing, Targeting therapies, Precision oncology, Oncogenic signaling pathways, Cancer immunotherapy

1. Introduction

CRISPRs are widely investigated as versatile biotechnological tools. The CRISPR locus contains CRISPR-associated (Cas) genes and an array of repeats separated by variable spacers. These spacers, taken from foreign genetic elements (1), store memory of exogenous nucleic acids and enable immunity by specifically recognizing and cutting matching pathogens (2) (Figure 1a). Guide RNAs are programmed with distinct spacer sequences that match the target DNA "protospacer" near the PAM, underscoring the key roles of spacers in gene editing and diagnostics (3). The protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM), a short, conserved DNA sequence adjacent to the CRISPR cleavage site, allows Cas proteins to distinguish self from foreign DNA. This interplay among CRISPR components, particularly spacers and PAMs, underpins the broad applications of CRISPR in gene editing and diagnostics. Cancers are complex biological systems that integrate tumor cells with various non-cancerous cells within a modified extracellular environment. The tumor microenvironment (TME), comprising cancer cells, immune cells, stromal cells, vasculature, and extracellular matrix, is essential for cancer initiation and progression and is associated with immune suppression, immune evasion, sustained proliferation, metastasis, and angiogenesis. Due to the pathophysiological complexity of the TME, current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches remain limited, highlighting the need for new technologies. CRISPR-Cas technology shows promise for effective, precise cancer diagnosis and treatment. In this review, we discuss the applications of CRISPR-Cas technology in analyzing and targeting the TME, highlighting its potential in molecular diagnostics and therapeutic strategies.

2. Mechanisms and Applications of CRISPR-Cas

2.1 Mechanisms and Functionality

The CRISPR-Cas system is categorized as class 1 and class 2. Class 1 systems are composed of multi-subunit protein complexes, while class 2 systems consist of a single-effector multidomain protein. These are commonly used as genome-editing technologies because of their simpler architecture. Class 2 is classified into types II, V, and VI, with the corresponding effector proteins Cas9, Cas12, and Cas13 (5). V-A and V-B refer to Cas12a and Cas12b (6), previously named Cpf1 and C2c1, respectively. While the CRISPR-Cas system shares a fundamental mechanism for targeting and cleaving DNA, it differs in aspects such as guiding RNA, PAM sequences, cleavage ends, and capacity for trans-cleavage. Cas9 is a DNA endonuclease guided by single-guide RNA (sgRNA), which consists of trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA) and CRISPR RNA (crRNA) (7). The upstream region of the CRISPR locus transcribes tracrRNA, which induces the maturation of another pre-CRISPR RNA (pre-crRNA) to generate active crRNA (8,9). The tracrRNA:crRNA complex, commonly referred to as sgRNA, can combine with CRISPR-associated nuclease 9 (Cas9) to form the CRISPR-Cas9 system (10). In the absence of sgRNA, Cas9 remains inactive and cannot cleave the target DNA sequence. PAM sequences, typically 2-5 bp located downstream of the CRISPR-targeted cleavage site, are essential for the CRISPR system first to recognize PAM and then unwind the DNA duplex to facilitate base pairing between the target DNA strand and the crRNA guide sequence (11). Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) was the first Cas9 nuclease used in genome editing (12), whose sgRNA could be easily programmed to guide the cleavage of almost any sequence preceding a 5’-NGG-3’ PAM sequence in mammalian cells, enabling various edits to the target locus (13). CRISPR-Cas9 variants exhibit PAM specificity, with StCas9 (S. thermophilus) requiring 5’-NNAGAAW-3’ and SaCas9 (S. aureus) recognizing 5’-NNGRRT-3’.

After binding to the PAM and forming a DNA-sgRNA hybrid complex, the Cas9 proteins can create a double-strand break (DSB) at a site three base pairs upstream of the PAM with its RuvC and the HNH nuclease domain (14), predominantly generating blunt-ended DSBs (Figure 1b). DSBs are one of the most genetically toxic DNA damages. If not repaired, they may lead to chromosomal rearrangement, genomic instability, and cell death. Thus, distinct pathways are employed in eukaryotic cells, resulting in differences in genome-editing accuracy and efficiency (15). HDR and NHEJ are two main strategies that cells use to deal with DSBs. The former is precise but limited by the requirement for large amounts of exogenous DNA templates, whereas the latter is efficient but error-prone. DSBs in CIRSPR-Cas9 are commonly repaired by the NHEJ pathway, resulting in either complete repair or the formation of small insertions and deletions (16). Consequently, gene editing can be achieved by generating DSBs at specific genomic sites, enabling processes such as gene knock-in, knock-out, gene repair, and transcriptional regulation (17).

The fundamental mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9 and CRISPR-Cas12 is substantially the same. For Cas12a, only crRNA is sufficient for mediating DNA targeting without tracrRNA (18), while the CRISPR-Cas12b system has both crRNA and tracrRNA (19). Cas12 family proteins have predominantly T-rich PAM sequences but differ in the number of Ts18. The PAM of CRISPR-Cas12a is TTTV, whereas that of Cas12b is TTN (20). Both Cas12a and Cas12b proteins contain a RuvC-like endonuclease domain and a nuclease lobe (NUC) domain for DNA cleavage, but they lack the HNH domains found in Cas9 (21). After the crRNA recognizes the PAM sequences that are located 18-23 nt upstream of the spacer and produces a DNA-sgRNA hybrid complex, Cas12 generates DSBs with staggered ends (Figure 1b), which can accelerate non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)-based gene insertion into the mammalian genome. Different from Cas12, Cas9 produces blunt-ended DNA breaks (21,22). After completing the cis-cleavage, Cas12 is activated and no longer relies on PAM; instead, it nonspecifically binds to any single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) to cleave, a process called trans-cleavage (23). Trans-cleavage can generate shorter DNA fragments, thereby facilitating signal amplification of the target DNA and revealing its nucleic acid detection ability (24). The unique characteristics of CRISPR-Cas12 can be effectively integrated with nucleic acid amplification (NAA) techniques to achieve point-of-care testing (POCT). CRISPR Cas9 and Cas12 are both DNA-targeting systems, while Cas13 is an RNA-targeting system. To efficiently target small single-stranded RNAs (ssRNAs), Cas13 requires a protospacer flanking site (PFS) rich in A and U at the 3’ end instead of PAM (25). Cas13 proteins typically contain two nucleotide-binding (HEPN) domains, one from higher eukaryotes and the other from prokaryotes, to cleave ssRNA (26). Compared to RNAi-mediated knockdown, Cas13-based RNA knockdown demonstrates a substantial reduction in off-target effects (27), making it particularly suitable for precise RNA manipulation and diagnostic applications.

2.2 Applications in Molecular Diagnosis and Precise Therapy

As a revolutionary gene-editing tool, CRISPR-Cas9 has demonstrated significant potential in molecular diagnostics and precise therapy in recent years (Figure 1c). By designing specific single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs), the system can precisely recognize and cleave target DNA, making it an ideal platform for clinical diagnostics and treatment. In antiviral therapy, CRISPR technology has been developed to edit CCR5 and HIV-1 to eliminate HIV-1 infection (28). In oncology, the CRISPR-Cas9 system is driving revolutionary advances in precision cancer medicine. CRISPR-Cas9 can be combined with next-generation sequencing (NGS) to analyze genomic variations and realize personalized cancer medicine (17). CRISPR-based platforms have been successfully applied to detect clinically significant biomarkers, such as pancreatic cancer-specific tsRNAs (29) and breast cancer markers (PIK3CA E545K ctDNA), enabling early cancer screening (30). Previous studies have demonstrated that employing CRISPR technology to knock out PD-1 in CAR-T cells can effectively augment T cell immune responses and enhance their capacity to eliminate cancer cells (31). With the successful application of CRISPR-Cas9, more CRISPR-Cas variants have been discovered, and they have demonstrated fantastic superiority as well.

Figure 1. Molecular mechanisms and applications of the CRISPR–Cas system. (a) The CRISPR-Cas9 adaptive immune system in prokaryotes. Its locus typically comprises an array of repetitive sequences interspersed with spacer sequences derived from invasive genetic elements, along with a suite of CRISPR-associated (Cas) genes. Preceding the cas operon is the tracrRNA gene. Upon phage infection, a new spacer acquired from the invading DNA is integrated into the CRISPR array. The transcribed pre-crRNA is processed into mature crRNAs by RNase III-mediated cleavage. These mature crRNAs assemble with tracrRNA and Cas proteins to form a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. During interference, the RNP identifies invading DNA via an sgRNA (tracrRNA:crRNA), and the Cas protein cleaves the foreign DNA, thereby eliminating the foreign gene. (b) The CRISPR-Cas9 system can cleave at 3 bp upstream of the dsDNA PAM, guided by the sgRNA, yielding blunt ends via the HNH and RuvC domains of Cas9. The CRISPR-Cas12a system relies solely on crRNA to recognize the PAM, then cleaves the non-complementary strand of the target DNA downstream of the PAM, producing staggered ends exclusively through the nuclease RuvC. (c) The application of the CRISPR-Cas system in different scenarios. Figure 1 was created by the authors using graphical components from Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com/), licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0) license.

Because CRISPR-Cas12 exhibits trans-cleavage, it has been applied across multiple fields. For example, in nucleic acid detection, DETECTR is a key mechanism that leverages the trans-cleavage capability of the Cas12a (23). In addition to DETECTR, other nucleic acid detection technologies based on CRISPR-Cas13 include SHERLOCK (32) and SUREST (33). Further details of these technologies will be elaborated in subsequent sections. CRISPR-Cas systems can be combined with microfluidic platforms for densely multiplexed assays, enabling rapid assessment of complex diseases and guiding precise treatment (34). Thus, CRISPR-based molecular diagnosis retains significant potential to advance clinical applications, particularly in oncology therapeutics. After Cas9 and Cas12a, Cas12b is the third promising CRISPR system for genome engineering (35). Different types of Cas12b have distinct advantages. Among the Cas12b family, AaCas12b from the Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus maintains optimal nuclease activity over a wide temperature range (31 °C-59 °C) and shows high specificity and minimal off-target effects, which can be a versatile tool for mammalian genome engineering (36). Cas12b can also be applied to DNA detection, a Cas12b-mediated DNA detection (CDetection) platform showing sensitivity and accuracy (37). Because specific subtypes of Cas12b exhibit high-temperature resistance, they are suitable for use in LAMP-based pathogen detection and screening (38). In contrast, the CRISPR-Cas12a system is temperature compatible with RPA (39). Compared to CRISPR-Cas9 and Cas12a, Cas12b holds potential applications in extreme-environment bioengineering and precision medicine due to its unique thermal stability and editing properties. However, its full potential remains to be further explored.

3. The Application of CRISPR-Cas in Analyzing the Complexity of TME

3.1 Functional Gene Screening

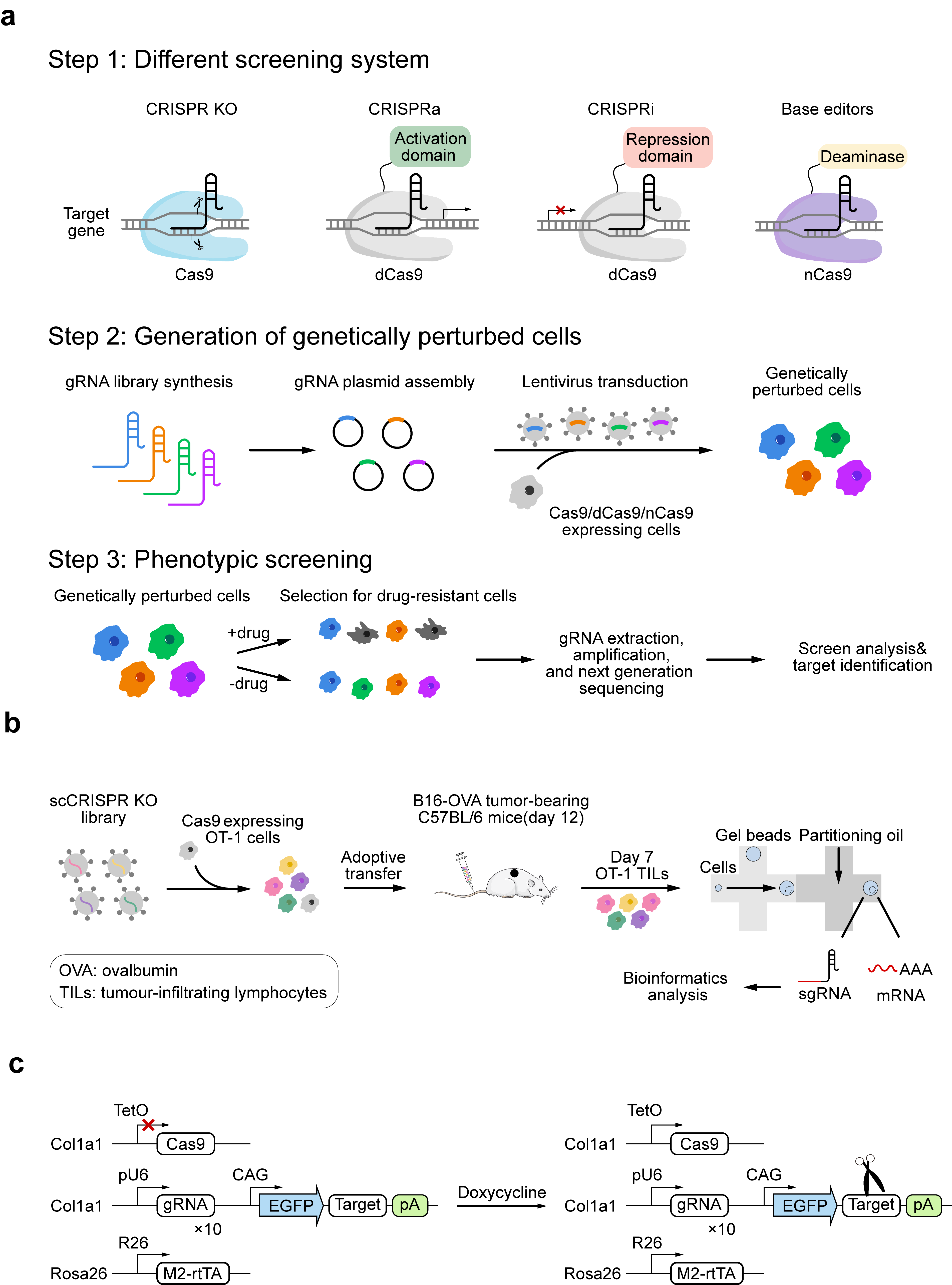

CRISPR-Cas9-based functional genetic screening (Figure 2a) has been extensively employed across diverse research domains, including investigations of tumorigenesis mechanisms, drug discovery, immunotherapy, and gene-function characterization. Compared to alternative methodologies such as RNA interference (RNAi) and cDNA overexpression, CRISPR-Cas9-based genome-wide screening offers distinct advantages of high throughput, enhanced efficiency, and reduced cost. Among CRISPR-based strategies, gene knockout (KO) screening represents the most established paradigm. For instance, KO screening in CD8⁺ T cells revealed that deletion of the transcription factor FLI1 induces 5- to 30-fold cellular expansion and enhances tumoricidal capacity (40). Separately, ADCY7KO was shown to increase CD8⁺ T-cell infiltration via transcriptional upregulation of the cytokine CCL5 (41). In polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells, the surface protein CD300ld is enriched in the TME, and its genetic deletion significantly suppresses neoplastic progression (42). Similarly, Genetic ablation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase COP1 in malignant cells reduces tumor-associated macrophage infiltration, thereby impeding tumorigenesis (43).

Beyond CRISPR KO, CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) and CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) constitute widely utilized functional genomic screening methodologies. CRISPR employs catalytically deactivated Cas9 (dCas9), which lacks endonuclease activity and therefore cannot introduce double-strand breaks in DNA. Instead, dCas9 is fused to transcriptional activators such as VP64, p65, and NF-κB to induce targeted gene transcription. Using this approach, studies have identified PRODH2 as a critical target whose activation significantly enhances the anti-tumor efficacy of CD8⁺ T cells (44). Joung et al. (45) discovered that transcriptional induction of BCL-2 and B3GNT2 drives tumor cell resistance to cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). Similarly, CRISPRi utilizes dCas9 fused to transcriptional repressor domains, such as KRAB or MeCP2, to suppress gene transcription. For instance, Li et al. (46) identified several genes, including ARPC4, PI4KA, ATP6V1A, UBA1, and NDUFV1, whose repression significantly enhances the tumor-killing efficacy of CAR T cells. In comparison to CRISPR KO, CRISPRa/I offer distinct advantages that include reduced off-target effects and reversible perturbation. However, these techniques may have limitations, including limited transcriptional modulation efficiency and potential epigenetic constraints at specific loci. Furthermore, researchers (47) have enhanced screening accuracy under high Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) conditions by incorporating unique internal barcodes (iBARs) within sgRNA constructs. This methodology significantly reduces experimental workload and improves screening fidelity compared to conventional approaches.

Base editor (BE) enables the precise introduction or correction of specific point mutations, allowing for the faithful recapitulation of the functional impact of single-nucleotide variants and single-nucleotide polymorphisms prevalent in cancer. Utilizing the cytosine base editor (CBE), researchers have demonstrated the feasibility of base editing for high-throughput screening of point mutations (48,49). This approach has been successfully applied to conduct functional screens for specific mutations in DNA damage response genes, such as BRCA1/2.However, the editing efficiency of base-editing tools varies significantly across genomic loci. Furthermore, an sgRNA can generate multiple types of mutations at its target site.

Consequently, the functional consequence associated with a screened sgRNA may not accurately reflect the intended variant effect. To address this limitation, an efficiency-correction model (50) can be implemented to transform the cellular effect induced by an sgRNA into a variant pathogenicity score, thereby enhancing the accuracy of functional variant assessment. iBARed Cytosine Base Editing-mediated Gene KnockOut (BARBEKO) is a novel high-throughput screening methodology that integrates CBE with sgRNAs incorporating iBARs (47,51). This method significantly reduces the number of cells required for library construction and is unaffected by copy number effects or editor-induced cytotoxicity. In colorectal cancer cell lines, employing cytosine base editors (CBEs) and adenine base editors (ABEs) to target core genes in the IFN-γ signaling pathway enables assessment of how distinct mutations affect the IFN-γ response and T cell-mediated cytotoxicity (52). To achieve base editing in primary human T cells, Schmidt et al. (53) employed optimized BE and screened multiple allelic pairs that regulate T cell activation and cytokine production.

Integrating CRISPR screening with single-cell analytical modalities, single-cell CRISPR screening (scCRISPR) provides a transformative tool for identifying cancer-associated genes within the TME. Building upon this platform, several sequencing methodologies have been developed, including Perturb-Seq (54,55), CROP-Seq (56), and Direct Capture Perturb-Seq (57). Using Perturb-Seq, Fagerberg et al. (58) first elucidated the pivotal role of the transcription factor KLF2 in governing the differentiation and exhausted states in CD8⁺ T cells. Specifically, KLF2 maintains effector T cell lineage stability by promoting TBET activity while suppressing TOX expression. In another study employing CROP-Seq, researchers identified a TNFR1-dependent macrophage tumor necrosis factor (TNF) signaling module that functions as a universal driver of clonal expansion in epithelial tissues (59). This discovery provides a mechanistic foundation for developing therapeutic strategies targeting the TNF signaling pathway.

Beyond Cas9-based screening platforms, Cas12a is also a viable tool for functional genetic screening. Utilizing the optimized AsCas12a variant (enAsCas12a), researchers identified 11 pairs of established synthetic lethal gene interactions in OVCAR8 and A375 cancer cell lines (60). This demonstrates the utility and potential of Cas12a for complex functional genomic screens. Furthermore, Cas13 enables programmable RNA targeting and knockdown in mammalian cells (61, 62). Unlike Cas9, Cas13 directly cleaves non-coding RNAs without altering genomic DNA sequences. Cas13-based screening of highly expressed circular RNAs (circRNAs) in cervical and colon carcinoma cell lines identified circRNAs essential for cell-type-specific proliferation (63). A parallel Cas13 screen across five human cell lines, including the THP-1 monocytic cell line, identified 778 essential long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) that play indispensable roles in human cancer pathogenesis and development (64). These findings highlight the promise of Cas13 as a powerful platform for interrogating non-coding RNA function in the TME. Following the widespread use of Cas9, Cas13 is poised to become a key tool in elucidating the roles of non-coding RNAs in tumorigenesis and cancer progression.

3.2 Dissecting Intercellular Interaction

Cell–cell interactions are central to tissue function and microenvironmental regulation, and CRISPR-Cas technologies provide powerful tools to interrogate their molecular regulators. Within the tumor microenvironment (TME), cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) exhibit marked heterogeneity, including progenitor-exhausted T cells (Tpex) and terminally exhausted T cells (Tex). Tex cells constitute the dominant CTL population in tumors, mediate tumor cell killing, but progressively lose proliferative capacity. To overcome this limitation, Zhou et al. (65) applied scCRISPR to map in vivo fate-regulatory networks of tumor-infiltrating T cells (Figure 2b). This analysis identified the transcription factors IKAROS, ETS1, and RBPJ as key regulators that control Tpex exit from quiescence and promote proliferation of terminal Tex cells, thereby revealing strategies for functional T cell reactivation.

MHC class I (MHC-I) antigen presentation (AP) is a critical determinant of CD8⁺ T cell specificity and activation and represents a significant target in cancer immunotherapy. CRISPR-based screens have uncovered multiple positive and negative regulators of the MHC-I AP pathway. For instance, interferon (IFN)-mediated upregulation of classical MHC-I molecules and the non-classical MHC-I molecule Qa-1b suppresses CD8⁺ T cells and NK cells, respectively, thereby facilitating tumor immune evasion (66). Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 acts as a negative regulator by transcriptionally silencing genes involved in MHC-I antigen processing (67). In addition, SUSD6, TMEM127, and MHC-I form a ternary complex that recruits the E3 ubiquitin ligase WWP2, promoting MHC-I ubiquitination and lysosomal degradation (68). Genetic disruption of SUSD6, TMEM127, or WWP2 enhances MHC-I AP and suppresses tumor growth in a CD8⁺ T cell-dependent manner.

Additionally, BIRC2 interacts with the NF-κB-inducing kinase. It promotes ubiquitin-dependent degradation, thereby inactivating the non-canonical NF-κB signaling pathway and downregulating MHC-I expression (69). Collectively, these findings underscore the complexity of the regulatory networks governing immune surveillance and identify potential targets to enhance antigen presentation and T-cell-mediated tumor clearance. Notably, a recently developed methodology termed Perturb-FISH (70) integrates CRISPR perturbations with spatial transcriptomics to capture how genetic perturbations influence intercellular interaction. The methodology has been employed to investigate the impact of NF-κB signaling pathway gene knockouts on tumor cell-immune cell interactions, thereby validating its utility in dissecting microenvironmental crosstalk. As a versatile molecular toolkit, CRISPR enables high-precision elucidation of intercellular interactions within the TME. This capability provides strategic frameworks for enhancing tumor cell immunogenicity and potentiating T-cell-mediated antitumor immunity, thereby advancing cancer immunotherapy.

3.3 Investigating TME Dynamics

CRISPR-Cas9 enables novel in vivo lineage tracing strategies by utilizing insertion/deletion (indel) mutations generated through targeted DNA double-strand breaks as heritable genetic barcodes. This approach reconstructs lineage relationships between cellular clones and quantifies dynamic clonal evolution. For example, Rogers et al. (71) combined CRISPR-Cas9 technology with DNA barcoding to enable precise tracking of every cell in mouse lung adenocarcinoma, providing a scalable, high-throughput platform for delineating cancer gene interactions. Sarah Bowling et al. (72) first reported a CRISPR-Cas9-based mouse model for lineage tracing, termed CARLIN, which is used in the CRISPR screening process (Figure 2c). However, its utility is constrained by limited barcode diversity and indiscriminate labeling of all cells. Addressing these limitations, the DARLIN (73) methodology innovatively substitutes Cas9 with Cas9-TdT fusion and implements a triple-target array, substantially enhancing barcoding resolution. The CREST system (74) employs analogous principles to resolve lineage relationships among diverse midbrain cell types in mice at specific developmental timepoints. Its key advantage lies in elucidating molecular mechanisms governing fate decisions at single-clone resolution.

In addition, Jonathan S. Weissman’s team (75) developed an alternative high-resolution CRISPR-Cas9 tracing system. This system incorporates a random integration barcode (IntBC) to encode clonal lineage information. It uses sgRNA-directed Cas9 targeting of three distinct loci to induce continuous indel formation, thereby capturing subclonal lineage trajectories over time. Leveraging this system, the team constructed a single-cell lineage tracer that mapped metastatic dissemination routes and identified metastasis-specialized subclonal clusters in lung adenocarcinoma, generating comprehensive cancer lineage trees that delineate spatial trajectories of disseminated tumor cells (76). Collectively, these methodologies provide powerful tools for investigating cellular lineage hierarchies and fate determination, offering strategic frameworks to dissect spatiotemporal dynamics and heterogeneity within the TME.

Figure 2. CRISPR-based functional screening strategies and single-cell applications. (a) CRISPR screening process. First, an appropriate screening system must be selected: (I) CRISPR KO: Cas9 is guided by gRNA to locate the target DNA sequence and cleave the DNA double strand. (II) CRISPRa: dCas9 fused to transcriptional activators promotes the transcription of target genes. (III) CRISPRi: dCas9 fused to transcriptional repressors suppresses the transcription of target genes. (IV) Base editor: Composed of dCas9 or nickase Cas9 (nCas9) combined with cytidine deaminase or adenine deaminase, this system enables the introduction of single-nucleotide mutations without inducing double-strand breaks. After selecting the screening system, the designed gRNA library is introduced into cells. After applying selection conditions (e.g., drugs), gRNA is extracted from surviving cells, amplified, and analyzed using next-generation sequencing to determine its target gene. (b) Researchers transduced Cas9-expressing activated OT-I CD8+ T cells (specific for ovalbumin (OVA)) with the scCRISPR library, then transferred cells to B16-OVA melanoma tumor-bearing mice. Seven days later, single-cell sgRNA and transcriptome libraries from tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in the mice were assessed via droplet-based sequencing. Subsequent bioinformatics analysis helped map the T cell gene regulatory network. (c) Schematic of the CARLIN system. The Col1a1 genetic locus contains gRNA arrays, target sites, and a doxycycline-inducible Cas9 cassette. Ten gRNA sequences are independently controlled by individual U6 promoters. The Rosa26 locus harbors an enhanced reverse tetracycline-controlled transactivator (M2-rtTA). Fig. 2a was adapted from Refs 97 and 98, licensed under CC-BY 4.0. Fig. 2b and 2c were created by the authors using graphical components from Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com/), licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0) license.

4. Application of CRISPR Technology in Tumor Microenvironment-Related Diagnostic Analysis

4.1 Applications of CRISPR Technology in Nucleic Acid Detection

Liquid biopsy is a noninvasive diagnostic method that enables early screening and diagnosis of tumors by detecting biomarkers, such as ctDNA, miRNA, DNA methylation, and exosomes, in samples such as blood and saliva (77). However, because ctDNA levels are low in blood (only 1% of cell-free DNA), amplifying variable signals is crucial. Currently, clinical quantitative detection is mainly based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques. Still, the expensive instruments and cumbersome operational procedures limit the use of PCR in basic home assays and point-of-care testing (POCT) (78). Recently, the CRISPR-Cas system has become widely applicable for molecular detection (79). Several CRISPR-Cas-based detection platforms, including DETECTR, HOLMES, and SHERLOCK, have been developed as point-of-care diagnostic tools enabling higher specificity and sensitivity in pathogen detection (80). ctDNA is a free DNA fragment released into the blood by tumor cells that carries information on gene mutations, copy number variations, aberrant methylation, and other genomic alterations. However, the low abundance of wild-type DNA in blood and the high background of wild-type DNA impede precise and specific measurement of ctDNA (78). Cas9 enables ctDNA detection through its DNA-targeting and precise cleavage capabilities. The primary detection mechanisms include pre-amplification, engaged amplification, and post-amplification. Using Cas9 before amplification removes background nucleic acids and enriches for rare targets. DeRisi et al. developed the DASH (81) technique, which uses Cas9 to enrich for targeted ctDNA and reduce interference from background wild-type DNA. The precise cleavage properties of Cas9 can also be used to distinguish amplification products after amplification, thereby improving detection specificity. During amplification, Cas9 relies on a specific protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) for cleavage; however, not all target sequences meet the PAM design requirements. To address this limitation, we can engineer Cas9 derivatives by altering PAM specificities. For example, Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) (82) can be modified to recognize alternative PAM sequences by leveraging structural information, directed evolution via bacterial screening, and combinatorial design. Later, researchers confirmed that Type II CRISPR-Cas9 systems, produced by crRNA and tracrRNA, exhibit trans-cleavage activity (83) on both ssDNA and ssRNA substrates, depending on the RuvC domain (84). Cas9 exhibits sequence preference for trans-cleavage substrates, preferring to cleave T- or C-rich ssDNA substrates. Based on the trans-cleavage activity of Cas9 and nucleic acid amplification technology, a DNA/RNA-activated Cas9 detection platform has been developed, enabling detection of trace nucleic acids via signal amplification.

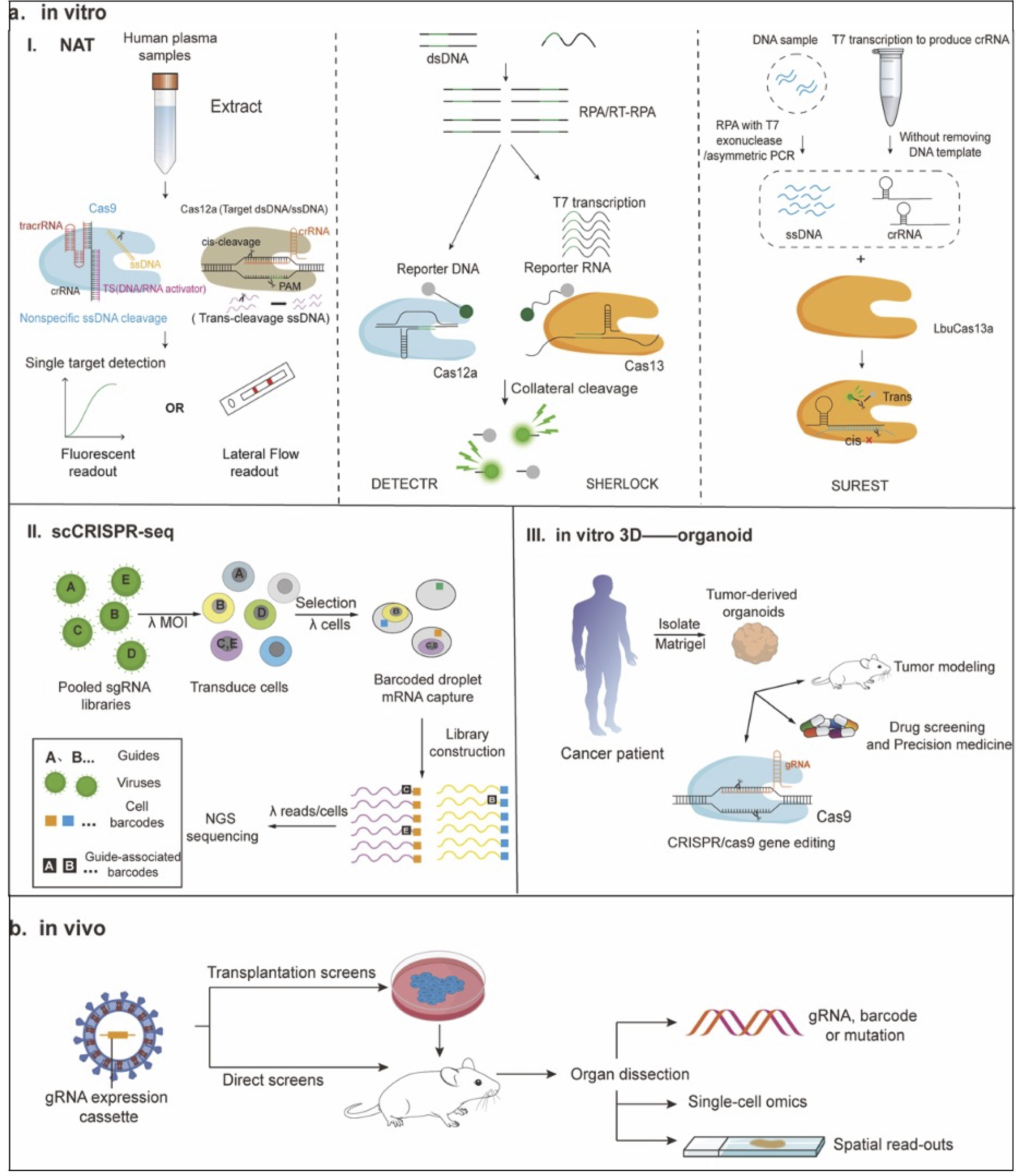

CRISPR-Cas12a proteins are used in molecular diagnostics. Unlike Cas9, Cas12a is guided by a T-rich CRISPR RNA and recognizes specific PAM sequences to bind and cleave double-stranded DNA. Upon site-specific cleavage, Cas12a undergoes a conformational activation and non-specific trans-cleavage activity against single-stranded DNA. This unique cleavage property has been exploited for nucleic acid detection. By integrating the trans-DNA cleavage activity of Cas12a with isothermal amplification methods, researchers developed the DETECTR platform (23). DETECTR is based on target-dependent activation of Cas12a, which induces indiscriminate cleavage of engineered ssDNA reporter substrates labeled with paired fluorophore-quencher moieties, resulting in a detectable fluorescence signal. This signal amplification strategy enables highly sensitive detection of target DNA sequences at the attomole level and provides a rapid, scalable approach for molecular diagnostics (Figure 3a).

Figure 3. CRISPR-enabled platforms for molecular diagnostics and functional genomics. (I) Nucleic acid detection: The trans-cleavage activity of Cas9 is activated upon binding to DNA or RNA targets. Cas12a allows for cis-cleavage and trans-cleavage. Subsequently, fluorescence detection or lateral flow readout is performed. DNA or RNA is amplified through RPA or RT-RPA, respectively. The amplified RPA products are converted into RNA through T7 transcription. When crRNA binds to its complementary target sequence, it activates the Cas enzyme, triggering collateral cleavage that quenches the fluorescent reporter. Thus, Cas13a (for the SHERLOCK system) or Cas12a (for the DETECTR system) indicates the presence of RNA or DNA target sequences, respectively. For Cas12 detection, the T7 transcription step is omitted, allowing direct detection of the amplified target. The fundamental principle of the SUREST platform is that the LbuCas13a-crRNA-ssDNA ternary complex exhibits significant trans-cleavage activity when targeted to DNA. (II) Perturb-Seq: By constructing the pooled sgRNA library and infecting cells with a pool of viral vectors encoding sgRNA, each cell’s mRNA (including GBC) is labeled with a unique cell barcode (CBC) and unique molecular identifier (UMI) for scRNA-seq. (III) Organoid technology can be used to model various human cancers, test drug efficacy and toxicity in precision medicine, and develop novel targeted therapies. In addition, synergistic use of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing can elucidate the pathophysiology of various cancers and investigate the effects of specific genetic changes on tissue function and disease progression. (b) In vivo CRISPR screening is divided into transplant screening and other types of in vivo screening. In transplantation screening, cells are transduced in vitro and then transplanted into adult animals. In direct screening, the gRNA library is delivered directly to the target tissue or cell type in the mouse. Subsequently, screening readouts are performed, with phenotypes measured as changes in gRNA or barcode abundance or frequency, or using single-cellomics or imaging techniques to record multidimensional phenotypes for each perturbation. Fig. 3a was adapted from Ref 89, licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), Fig. 3b was created using graphical components from Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com/), licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0).

SHERLOCK (32) is a nucleic acid detection technology based on CRISPR-Cas13 and RPA, which amplifies DNA or RNA using RPA or RT-RPA, respectively. For CRISPR enzymes targeting RNA (including Cas13a), amplified RPA products are converted into RNA by T7 transcription. When crRNA binds to its complementary target sequence, it activates the Cas enzyme, triggering collateral cleavage that quenches the fluorescent reporter. Additionally, Wu et al. developed a new nucleic acid detection platform, the Superior Universal Rapid Enhanced Specificity Test (SUREST), using LbuCas13a (33). Studies have shown that the LbuCas13a-crRNA-ssDNA ternary complex exhibits significant trans-cleavage activity against DNA. Compared with conventional CRISPR-Cas systems, SUREST can target DNA specifically and directly without being restricted by the PAM sequence, opening new avenues for its application in molecular diagnostics. Without amplification, the detection limit of the CRISPR-Cas12a RNA-guided complex is only at the pico-molar level. Therefore, a platform called CRISPR-ENHANCE (85) (Enhanced Analysis of Nucleic acids with CrRNA Extensions) was developed. The trans-cleavage ability of target-activated LbCas12a is enhanced when the 3′ end of crGFP is extended by ssDNA and ssRNA. At the same time, the specificity of target recognition was significantly improved. The platform, based on engineered crRNAs and optimized conditions, enables the detection of multiple clinically relevant nucleic acid targets with higher sensitivity, achieving femtomolar detection limits without any target pre-amplification steps.

miRNAs are endogenous, short-stranded non-coding RNAs (86) (18-23 nucleotides), whose abnormal expression is closely related to the occurrence and development of tumors. However, miRNAs are short, low in abundance, and exhibit high sequence similarity within miRNA families; therefore, the sensitivity and specificity of their detection are of particular importance. RT-qPCR is the gold standard technique for detecting miRNA (87), but due to its high cost, researchers have turned to the CRISPR-Cas enzyme system. Researchers have developed a series of detection methods based on the CRISPR-Cas12a system, combining CRISPR-Cas12a with technologies such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), exponential amplification reaction (EXPAR), recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA), rolling circle amplification (RCA), and microfluidic systems. They have the advantages of high sensitivity and low detection limits. Despite its advantages in simplicity and specificity, the CRISPR-Cas system still relies on independent pre-amplification, which limits its clinical applications.

As a result, Jain et al. developed the Split Activator for Highly Accessible RNA Analysis (SAHARA) (88). In the presence of a split activator, multiple Cas12a homologs will activate trans-cleavage. The method detects picomolar concentrations of RNA without sample amplification, strand replacement, or reverse-transcription by simply supplying a short DNA sequence complementary to the seed region. However, picomolar levels (250-700 pM) of RNA are not sufficient for clinical assays. The researchers then improved the “Cas12a-crRNA split-activator” complex into the split Cas12a system (SCas12a (89)), in which the Cas12a enzyme binds to a split crRNA containing both scaffold RNA and spacer RNA components. By utilizing miRNA targets as spacer RNA and another ssDNA as the activator, SCas12a-based fluorescence and rapid lateral flow assays were developed. It can distinguish between mature miRNA and pre-miRNA with identical sequences (89). This method enables highly sensitive and selective miRNA detection without the need for reverse transcription or pre-amplification, with a limit of detection (LoD) of 100 femtomoles (fM). Similarly, another study developed an asymmetric CRISPR assay that does not require pre-amplification or reverse transcription, utilizing the asymmetric trans-cleavage behavior of competitive crRNA. The competitive reaction between a full-sized crRNA and a split crRNA in CRISPR-Cas12a induces cascade signal amplification and significantly improves target detection.

Research found that Cas12a could directly recognize RNA targets when the RNA was located at the 3’ end of the crRNA and supported by a DNA at the 5’ end of the crRNA, implying that CRISPR-Cas12a could recognize fragmented RNA/DNA targets, enabling direct detection of RNA (90). The assay sensitivity is 856 aM. In contrast to SCas12a, asymmetric CRISPR not only involves a complex reaction system but also relies on the full-length crRNA, effectively inhibiting Cas12a system activation in the presence of split crRNA and corresponding substrates. This effectively prevents false-positive results, but achieving this suppression requires relatively stringent conditions.

Not only can we reduce false positive results by avoiding pre-amplification, but we can also reduce them through a one-step, one-pot, isothermal CRISPR-Cas12a assay called “Endonucleolytically Exponentiated Rolling Circle Amplification with CRISPR-Cas12a” (EXTRA-CRISPR (86)). This method integrates multiple reactions, including target-mediated ligation, RCA, Cas12a binding, and nucleolytic cleavage, into a single reaction network. It uses cis-cleavage activity to convert conventional linear RCA into one that exponentially amplifies the target sequence, while employing the trans-cleavage reaction for amplicon detection and signal amplification. Its analytical performance is comparable to RT-qPCR, including high sensitivity with a single-digit femtomolar detection limit, single-nucleotide specificity, and rapid, flexible turnaround (analysis times ranging from 20 minutes to 3 hours, depending on the target and sample). This dramatically simplifies the assay process and facilitates POC diagnosis.

Additionally, a Cas12a-assisted in vitro diagnostic tool can be used to discriminate single-CpG-site methylation in DNA. This method uses methylation-sensitive restriction endonucleases (MSREs) (91) to digest non-methylated sequences, thereby fragmenting the target sequences and affecting R-loop formation between the crRNA and the target DNA. By analyzing the effects of fragment size, cleavage position, and fragment quantity on the trans-cleavage activity of ssDNA, the methylation sites can be inferred. This approach enables the study of individual CpG methylation sites for disease detection. Limitations of CRISPR-Cas diagnostic techniques include cleavage of off-target DNA (92) and the difficulty of developing multiplexed detection formats for single-tube assays. The cleavage of off-target DNA can lead to false-positive diagnoses, and specificity can be improved by engineering the guide RNA (93) or by modifying it to incorporate DNA (94) into the Cas9 gRNA (95). It isn’t easy to develop multiplexed detection formats in single-tube detection. Because the CRISPR system relies on an undifferentiated trans-cleavage mechanism. The researchers divided the process into two steps, each with a separate NAA and CRISPR assay. However, the liquid transfer process is cumbersome and susceptible to aerosol contamination, which may lead to false-positive results.

The research developed “The one-pot CRISPR detection strategy (96)”, which can be achieved by optimizing reaction components, performing physical or chemical separation, and selectively targeting amplification products. To achieve optimal detection efficiency, precise control of Cas12 cleavage activity is essential. For example, the cleavage activity of the CRISPR-Cas12a system can be regulated by altering the PAM site. When mediated by non-optimal PAM sites, cleavage efficiency is reduced, but INA is hardly affected. The altered PAM-site strategy was shown to be infeasible in CRISPR-Cas12b, possibly due to loss of cleavage activity resulting from mutation of the TTN site. Therefore, a one-pot assay strategy combining CRISPR-Cas12b mutants and LAMP amplification was developed to weaken the binding affinity of Cas12b proteins for target DNA by modifying their PAM recognition domains.

Additionally, the RG4 structure (97) can be added to the 5’ end of crRNA to control the activity of Cas12a. By introducing a PC linker between the RG4 and DR regions (G4-PC-DR), a light-controlled system can be established to activate any Cas12a target by replacing the spacer region. In addition, we can modify and demodify the 3′ end of the direct repeat (DR) region (98) to control Cas12a activity.

In response to the limitation that the CRISPR system relies on indiscriminate trans-cleavage mechanisms and the difficulty of differentiating between highly similar nucleic acid sequences, the researchers developed a method termed the Cas12a cis-cleavage-mediated lateral flow assay (cc-LFA) (99). This method uses a dual-key recognition mechanism based on CRISPR-Cas12a cis-cleavage and invasive hybridization of the released sticky-end DNA product. It integrates multiplexed nucleic acid amplification, a dual-key Cas12a detection mechanism, and a lateral-flow detection platform. Compared with the three mainstream CRISPR diagnostic technologies based on trans-cleavage, such as SHERLOCK, DETECTOR, and the Cas9-based CASLFA platform, cc-LFA exhibits higher specificity for the same DNA target. This technique enables single-base-resolution detection without interference from high concentrations of wild-type DNA.

4.2 Advances and Applications of Single-Cell CRISPR Screening Technology in Analyzing Tumor Heterogeneity

Cellular heterogeneity is manifested as phenotypic differences among cells, but ensemble-averaging methods mask these differences and the unique characteristics of individual cells (100). Single-cell sequencing analysis enables in-depth examination of cell populations by focusing on intercellular differences in expression profiles, preventing heterogeneity within individual cells from being masked by the homogenization of large numbers of cells. CRISPR technology, combined with highly multiplexed assays such as single-cell sequencing and spatial omics, facilitates analysis of tumor cell heterogeneity. They are the primary approaches for rapidly identifying cancer driver genes or tumor immune regulatory factors.

Perutrb-seq (55) and CRISP-seq (101) are the first scCRISPR-seq platforms developed to analyze the transcriptional changes after gene perturbation at the single-cell level. Both Perturb-seq and CRISP-seq rely on indirectly labeled sgRNA, but there is a certain probability of error in pairing GBC or UGI with sgRNA (Figure 3a). Later, CROP-seq was developed (102). It reads the gRNA directly without requiring an additional barcode. However, the loading capacity of the vector is limited, and CROP-seq is not compatible with the delivery of multiple sgRNAs. Direct Capture Perturb-seq technology (103) addresses the limitations of CROP-seq by detecting multiple different sgRNA sequences in a single cell. We designed platforms for direct capture with both 5’ and 3’ scRNA-seq. The approach enables sequencing of expressed sgRNAs alongside the single-cell transcriptome, thereby directly pairing sgRNAs with phenotypes. At the same time, hybridization-based target enrichment technology can be used to sequence thousands of specifically selected transcripts. While maintaining a high intronic phenotype, the required sequencing is also reduced. Targeted Perturb-seq (TAP-seq) (104) can also enrich for target genes, thereby significantly decreasing sequencing depth and enhancing the detection of low-expression genes. By defining a predefined target gene set, the multiple-testing problem in traditional Perturb-seq (105) was addressed. Subsequently, some studies were conducted to reduce costs. Researchers developed the “compressed Perturb-seq105” technologywhich, based is nbased of compressed sensing theory. Two methods are included: cell pooling (overloading the microfluidic chip to generate multicellular droplets) and guided pooling (high MOI infection to make cells contain multiple guides).

DNA barcoding technology can be analyzed only at the mixed cellular level and provides limited phenotypic analysis. In response, the researchers developed Pro-Codes (106). Pair each Pro-Code with different CRISPR gRNAs and conduct high-dimensional proteomic phenotypic analysis at the single-cell resolution for hundreds of genes. However, existing pooled CRISPR screening methods cannot provide information on extracellular events. Removing genes from the tissue environment results in the loss of much information. Therefore, the Perturb-map (107) was developed. It combines multiple imaging and spatial transcriptomics (108) while preserving spatial structure (109) and simultaneously analyzes the phenotypes of dozens of genes in tissues or tumors at the cellular resolution. The technique revealed that knocking out Tgfbr2 promotes tumor growth and transforms the TME into a fibromuscular state that excludes T cells.

In contrast, knocking out Socs1 promotes tumor growth and also leads to T-cell accumulation in the tumor. Perturb-map can be combined with an ovarian cancer mouse model (110) that highly simulates the dissemination and heterogeneity characteristics observed in human ovarian cancer. It can reveal how factors influence tumor cell-immune cell interactions and ultimately affect immune therapy responses. However, Perturb-map sacrifices the advantages of the pool-cloning workflow by using protein barcodes, and the spatial resolution of Visium limits its applicability to non-clonal growing cells. Therefore, the researchers turned to imaging spatial transcriptomics (iST) and developed Perturb-FISH (111). This method combines multiplexed error robust fluorescence in situ hybridization (MERFISH) with in situ amplification of gRNA to achieve simultaneous spatial detection of gRNA and mRNA. The feasibility of the technique can be verified by screening for ASD risk genes in astrocytes and by recording calcium activity responses to ATP stimulation. OPS research uses information-rich phenotypic and functional readouts, such as live-cell imaging or cell staining. It uses a library covering the entire human genome to explore the functional consequences of gene disruption. However, traditional OPS is limited to low-throughput phenotyping because it is difficult to efficiently and accurately detect disturbed barcodes. PerturbView (112) was developed as a novel optical pool screening (OPS) technology. This technology uses in vitro transcription (IVT) to amplify barcodes before in situ sequencing, enabling screening with highly multiplexed phenotypic readouts across various systems, including primary cells and tissues. PerturbView is compatible with multi-phenotype analysis and spatial omics reads, enabling more comprehensive interpretation of the effects of genetic perturbations and tracking of cell status in both healthy and diseased conditions. PerturbView can detect barcodes in situ within tissues, promoting the development of in vivo operations in animal models.

In addition to transcriptomics, the integration of CRISPR functional screening with proteomics and epigenomics provides new perspectives for cancer research. ECCITE-seq (113) can simultaneously detect the transcriptome, proteins, clonal types, and CRISPR perturbations. ECCITE-seq has higher sensitivity in detecting expression phenotypes. Another parallel method, “Perturb-CITE-seq (114)”, combines scRNA-seq analysis and CITE-seq to study single-cell surface proteins under perturbed conditions. It can be applied to patient-derived tumor immune models to analyze immune regulatory factors. Most single-cell multi-omics techniques used to analyze chromatin accessibility (115,116) are derived from the transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing (ATAC-seq) method (117). It utilizes the hyperactive transposase (Tn5) to measure the activity of regulatory DNA elements.

Subsequently, the Perturb-ATAC was developed. It is based on ATAC-seq and simultaneously detects CRISPR-guided RNA and open chromatin sites. It realizes a direct association between genotype and epigenetic phenotype. However, it is limited by high cost and low throughput. Spear-ATAC (118) and CRISPR-sciATAC (119) were developed. Spear-ATAC reads sgRNA intervals directly from genomic DNA, unlike previous techniques that read from RNA transcripts. CRISPR-sciATAC employs a two-step combinatorial indexing process to label DNA molecules and assign them unique cellular barcodes, without requiring specialized equipment. Both techniques break through the limitations of high cost and low throughput. A single-cell CRISPR screen enables simultaneous analysis of genetic disruption and high-dimensional phenotypes in single cells. However, its application is limited to a few hundred genetic perturbation studies. Subsequently, CRISPRi (120) was developed to analyze the effects of thousands of loss-of-function genetic perturbations in different cell types. Moreover, this technology has produced the first comprehensive map that integrates the genotype and phenotype of human cells. Using CRISPR KO screening in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cells (121), it was found that gene deletion either positively or negatively alters PDAC cell survival when MEK signaling is inhibited. CRISPR screening can be applied to identify drug targets and predict drug responses in cancer cells. The DREBIC method can capture the relative essentiality of drug targets (CRISPR screening activity score) and their relative abundance. It enables precise medicine by simulating overall drug responses and identifying drug-specific vulnerabilities associated with carcinogenic mutations.

CRISPR screening using organoids is the next level in in vitro systems, providing a model for revealing the genetic mechanisms of gene-drug interactions. Patient-derived organoids (PDOs) have been widely used in the study of various types of cancer, including colorectal cancer (CRC), lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, and liver cancer (122) (Figure 3a). For example, genome-wide CRISPR screening in 3D spheroids and xenograft tumors based on human non-small cell lung cancer cell lines showed that depletion of carboxypeptidase D (CPD) prevented tumor growth in spheroids and in vivo but was ineffective in 2D cultures. Growth phenotypes in 3D more accurately reflect observations in tumors. CRISPR screening can also be applied to primary human 3D gastric organoids (123) to identify genes that affect cisplatin sensitivity. In addition, CRISPR-mediated gene-engineered mouse models (CRISPR-GEMMs) (124) have been developed. For example, by combining the RCAS-TVA (125) and CRISPR-Cas9 systems, researchers developed an in vivo somatic-cell genome-editing mouse model. It can perform precise genetic modification on specific cell types to accurately model human tumors. The successful application of CRISPR-GEMMs depends on the effective delivery of interference reagents to target cells, which varies across different organs and cell types. Therefore, to date, CRISPR-GEMMs have been limited to cancers of the liver, lung, and brain. However, traditional 3D organoid cultivation techniques cannot precisely control the various factors in the TME over both time and space. It is essential to identify interacting regulators in TME. MEN1 (126) was identified as the most significant target, leading to differential shedding effects in vitro and in vivo. It has tumor microenvironment-dependent carcinogenic and anticancer functions. Therefore, in vivo screening via allogeneic transplantation of homologous mouse cancer cells, or via ex vivo or in situ transplantation of patient-derived cells (PDXs), is more closely aligned with a functional TME. These methods have led to the identification of genes associated with cancer cell immune escape or immune checkpoint blockade.

Therefore, CRISPR-based in vivo screening can be employed to identify immune regulatory genes that may serve as cancer prognostic markers, diagnostic markers, or potential drug targets. However, errors during cancer cell transplantation may confound screening results. Therefore, researchers developed an in situ CRISPR-Cas9 lung cancer screening method. By combining this approach with the adoptive transfer of cytotoxic T cells targeting tumor antigens in the model, the function of genes embedded in their native tissue structures was evaluated. It identified the known immune-escape factors Stat1 and Serpinb9, and the cancer testicular antigen Adam2 (127) as an immune-regulatory factor.

Furthermore, through an in vivo pooled CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis screening, it was discovered that Regnase-1 (128) is the primary negative regulator of antitumor responses. PTPN2 and SOCS1 can, in the context of Regnase-1 deficiency, enhance antitumor immunity. Regnase-1-deficient CD8+ T cells are reprogrammed into long-lasting effector cells within the TME, resulting in significantly improved therapeutic effects in mouse melanoma and leukemia through enhanced BATF function and mitochondrial metabolism. In addition, additional screening was conducted in the E0771-OVA triple-negative breast cancer (129) and GL261 glioblastoma models (130) implanted in situ. These screens identified negative regulators of T cell responses, including DHX37, PDIA3, and MGAT5.

High-throughput in vivo genetic perturbation screening facilitates a deeper understanding of cell interactions. In vivo CRISPR screening (131), including transplantation-based screening and direct in vivo screening. Screening readouts are categorized as count-based and information-rich. In count-based screening, the phenotype is measured as the change in the abundance or frequency of a specific perturbation or perturbation identifier (e.g., gRNA or barcode). Information-rich screening uses single-cell omics or imaging to document multidimensional phenotypes for each perturbation (Figure 3b). In vivo screening yields less reliable gene identification due to bottleneck effects, increased overall noise, and delivery problems. Noise primarily arises from intercellular heterogeneity (132) and library-bottleneck effects. CRISPR screening relies on the hypothesis that cellular phenotypes are directly caused by experimentally induced perturbations. Intercellular heterogeneity threatens this hypothesis. For transplantation screening, bottlenecks include the model's upper limit on injection volume and the possibility that transplanted tumor cells may die. To address these issues, we could increase library representation, but this would significantly reduce the size of viable screening libraries, thereby averaging out behavioral inconsistencies across many cells carrying the same sgRNA. We can also create monoclonal cell lines. CRISPR nucleases are delivered in batches to the cell lines, which are then isolated as single cells through FACS sorting or serial dilution, followed by the growth of clonal lines. In direct in vivo screening, the process is often hampered by poor delivery efficiency. Faced with high noise in CRISPR-Cas9 in vivo screening, researchers developed CRISPR-STAR (133). By randomly activating sgRNAs and employing an internal control mechanism, the interference of cell growth heterogeneity and genetic drift with the experimental results was effectively mitigated, thereby significantly reducing experimental noise. It also conducted a genome-wide screen in Braf inhibitor-resistant mouse melanoma cells to identify specific genetic dependencies in vivo. It highlights the relevance of functional genetics in identifying potential novel drug targets.

5. CRISPR-Cas Delivery Systems: A Critical Determinant of Therapeutic Success

Efficient delivery of the CRISPR-Cas gene-editing system to cancer or immune cells is pivotal to its successful application in cancer therapy. Currently, three primary modalities are employed to achieve CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing in target cells, including delivery of plasmids encoding the Cas9 protein and sgRNA, delivery of Cas9 mRNA together with sgRNA, and delivery of the Cas9 protein and sgRNA, either as separate components or as a pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex (134).

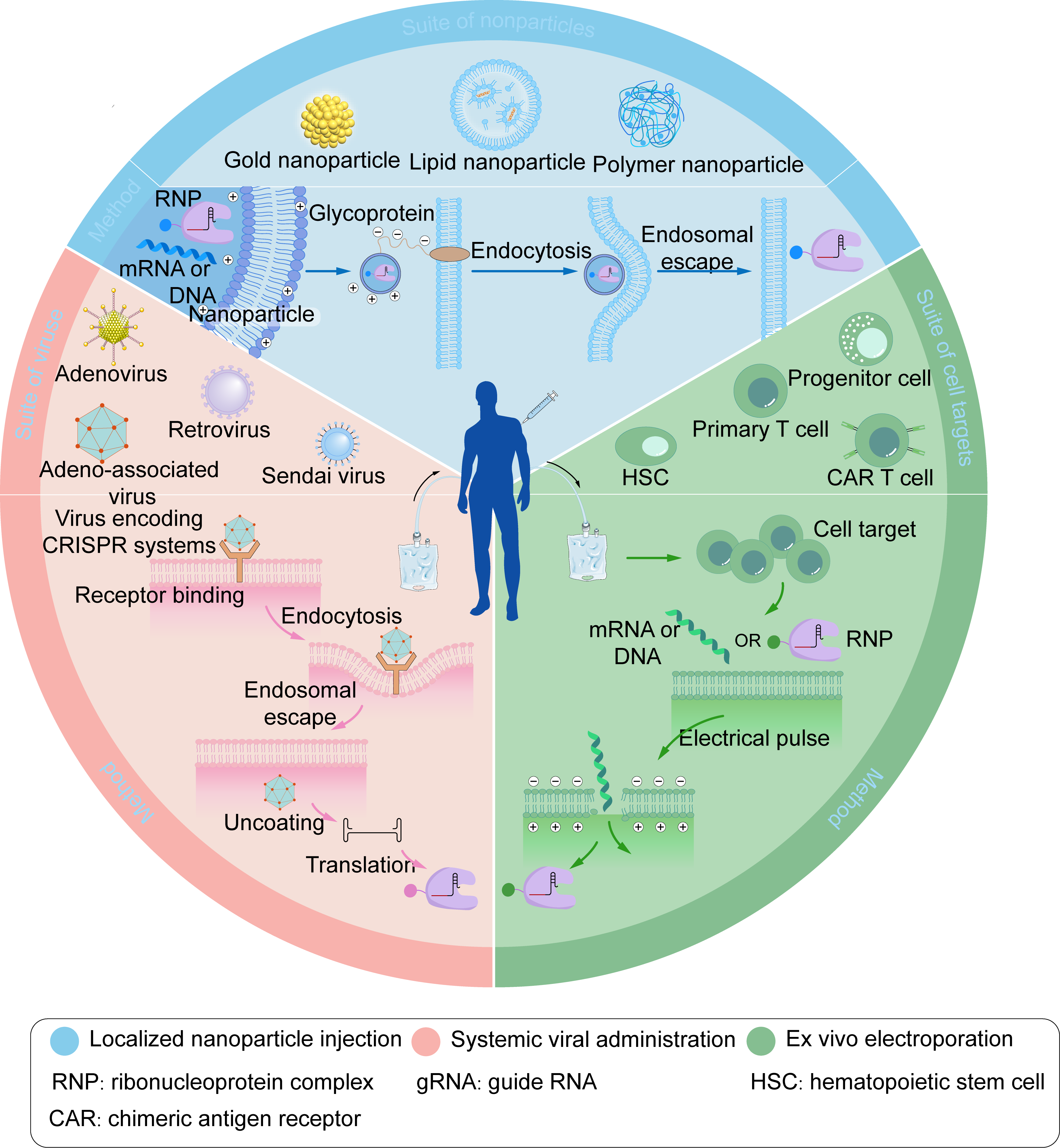

Delivery strategies are broadly categorized into viral vectors, non-viral vectors, and physical methods (Figure 4). Viral vectors are relatively mature delivery platforms, including adeno-associated virus (AAV), lentivirus, and adenoviral vectors. While viral delivery offers high transfection efficiency, potential off-target effects and safety concerns limit its broader applicability. In contrast, non-viral vectors offer notable advantages, including low immunogenicity, high biocompatibility, enhanced safety, and lower production costs. This category encompasses liposomes, lipid-like nanoparticles, gold nanoparticles, virus-like particles, and cell-penetrating peptides. Among these, nanoparticle-based carriers demonstrate considerable potential for clinical translation (135) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Three representative CRISPR delivery strategies include localized nanoparticle injection, systemic viral administration, and ex vivo electroporation.

Nanoparticles loaded with mRNA, DNA, RNP, or viruses encoding CRISPR systems undergo receptor recognition, endocytosis, and endosomal escape, ultimately releasing the mRNA, DNA, or RNP into the cytoplasm. Electroporation utilizes high-voltage electrical pulses to deliver substances through transient tiny pores in cell membranes. Blue: Localized nanoparticle injection. RNP: ribonucleoprotein complex. ACR: chimeric antigen receptor. Pink: Systemic viral administration. gRNA: guide RNA. Green: Ex vivo electroporation. HSC: hematopoietic stem cell. Figure 4 was created by the authors using graphical components from Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com/), licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0) license.Physical methods facilitate entry by transiently disrupting the cellular membrane, including microinjection, electroporation, and sonoporation. However, the clinical application of physical methods is hindered by the challenge of determining optimal parameters that preserve the native properties of human tissues. The characteristics, optimization strategies, and suitable application scenarios for each of these delivery approaches have been extensively reviewed (8, 136-138). Collectively, these three delivery modalities have been successfully applied in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo to enable CRISPR-Cas-mediated gene editing in cancer cells or immune cells (135, 139). AAV represents a classic vector platform for gene therapy (140). However, the commonly used nuclease Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) has a coding sequence of approximately 4.2 kb. The addition of essential gene regulatory elements brings the total size close to the AAV packaging limit (~4.7 kb), thereby constraining practical utility (141). The development of miniaturized CRISPR-Cas systems constitutes an alternative solution. The early-reported Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 (SaCas9), with a gene size of 3.2 kb, can be co-packaged with sgRNA into a single AAV vector and has been successfully employed for in vivo gene editing (142). Numerous other compact Cas9 orthologs have since been identified and characterized, including NmCas9 (Neisseria meningitidis) (143,144), CjCas9 (Campylobacter jejuni) (145), SauriCas9 (Staphylococcus auricularis) (146), BlatCas9 (Blatticella germanica) (146), Nme2Cas9 (Neisseria meningitidis) (147), and IscB (putative ancestor of Cas9) (148). Commonly utilized Cas12a variants, such as Acidaminococcus sp Cas12a (AsCas12a) and Lachnospiraceae bacterium Cas12a (LbCas12a), exhibit sizes comparable to SpCas9 and are similarly constrained by the AAV payload capacity. Consequently, more minor Cas12 variants have been actively explored, including AaCas12b (Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus), BhCas12b (Bacillus hisashii), DpbCas12e (Desulfofundulus piezophilus), Cas12j (Uncultivated phage), and Cas12f (also known as Cas14-derived) (149-153). Among these, Cas12f nucleases represent the most compact CRISPR nucleases identified to date, typically half the size of conventional Cas9 and Cas12a, but their editing efficiency is generally lower. Cas12f engineered through rational mutagenesis exhibits markedly enhanced editing activity and reduced off-target effects and has been successfully applied to ameliorate choroidal neovascularization in mouse models of macular degeneration (154). The incorporation of an α-helical domain at the N-terminus of the Un1Cas12f1 variant (CasMINI) (155), or the fusion of T5 exonuclease to either its N or C terminus (156), enables hyper editing efficiency in mammalian cells. Furthermore, compact members of the Cas13 family, such as Cas13bt (157), Cas13X (158), and Cas13Y (158), are sufficiently small for single-AAV packaging and effectively mediate RNA editing.

The efficacy of gene editing at tumor sites is affected by non-specific delivery and multiple intra- and extracellular barriers. TME-based stimuli-responsive CRISPR-Cas delivery systems provide a promising strategy for targeted editing, including redox-, pH-, enzyme-, ATP-, and microRNA-responsive platforms (159,160). For instance, a pH- and light-dual-responsive CRISPR nanotherapeutic (161), comprising a thioether-cross-linked polylex core and an acid-cleavable polymer shell, maintains structural stability in systemic circulation while preferentially accumulating in acidic TMEs. Subsequent laser irradiation triggers spatiotemporally controlled activation of the CRISPR system, enabling precision therapy at tumor sites.

Incorporation of targeted ligands can further enhance delivery efficiency. The short peptide Angiopep-2 binds explicitly to low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP-1), which is abundantly expressed on both blood-brain barrier (BBB) endothelial cells and glioblastoma cells (162). Therefore, Angiopep-2-functionalized glutathione-responsive nanoparticles can penetrate the BBB and selectively target glioblastoma (163,164). Similarly, nanoparticle surface coatings composed of hyaluronic acid and trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) at optimized ratios exploit TMAO’s anti-adhesive properties to facilitate penetration of intestinal mucus, thereby accumulating in colorectal tumor tissues via specific transcytosis across intestinal epithelia (165). Notably, erythrocyte membrane coatings (166) or erythrocyte-tumor cell hybrid biomimetic membranes (167) substantially outperform conventional chemical modifications by leveraging inherent immune-evasive properties, thereby enhancing targeting specificity, prolonging systemic circulation, and reducing immune clearance.

6. The Application of CRISPR Technology in Precision Therapy Targeting the TME

CRISPR-Cas gene-editing technology programmability and target specificity offers a powerful tool for cancer treatment (168). The tumor microenvironment (TME), a critical factor in tumor progression and treatment resistance, is heterogeneous. This heterogeneity makes it difficult for traditional therapies to achieve precise targeting, limiting efficacy and causing significant toxicity (169). However, the CRISPR-Cas system enables precise intervention within the TME; the following section details its specific applications.

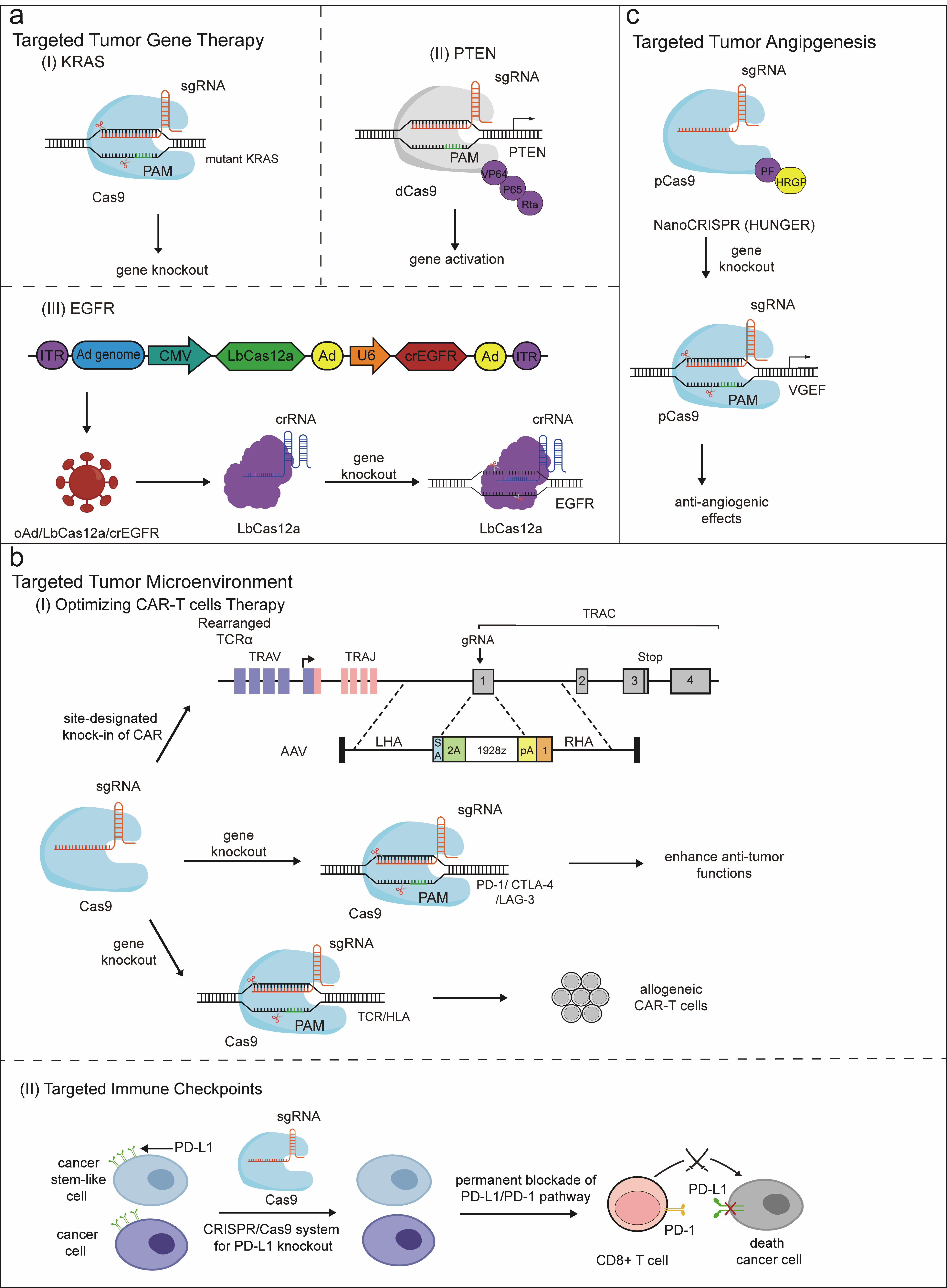

6.1 Application of CRISPR Technology for Direct Gene Editing in Tumor Cells

Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes play crucial roles in cancer pathogenesis, influencing tumor treatment resistance and progression (170). Abnormalities in oncogenes are typically associated with genetic mutation or abnormal amplification, which lead to overexpression of their encoded proteins, thereby causing uncontrolled cell growth and proliferation (171). CRISPR-Cas9 technology can specifically target and knock out oncogenes such as MYC, KRAS, HER-2, MIEN1, MASTL, and EGFR, providing precise intervention strategies for tumor treatment (172,173). For instance, MYC is overexpressed in most human tumors, driving cancer cell growth and proliferation by affecting physiological processes such as gene expression, cell differentiation, and angiogenesis, and by interfering with apoptosis and DNA repair. Therefore, MYC-targeted therapy has become an essential strategy for treating malignant tumors (174). The KRAS oncogene is also a crucial target for cancer therapy (Figure 5a). Research has shown that using CRISPR-Cas9 to target mutant KRAS genes can effectively inhibit the survival and proliferation capacities of cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo. It opens up new avenues for the treatment of malignant tumors such as colorectal cancer, lung cancer, and pancreatic cancer (175). Additionally, another study has shown that knockdown of the HPV E6 and E7 genes using CRISPR-Cas9 can reduce cell viability, increase p53 and p21 expression, and significantly inhibit proliferation of HPV-driven cancer cells (176).

Reversing drug resistance is also an essential strategy in cancer cell therapy. The fundamental reason lies in the emergence of mutations in drug resistance genes in tumor cells. At the same time, knockout chemotherapy resistance genes using CRISPR-Cas9 is expected to play a significant role in overcoming drug resistance. For example, the Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor (NRF2) is involved in the evolution of drug resistance in lung cancer. Studies have shown that after knocking out the NRF2 gene in chemotherapy-resistant lung cancer cells using CRISPR-Cas9, the efficacy of anticancer drugs such as cisplatin, carboplatin, and vinorelbine is restored, inhibiting tumor growth (177,178). Similar findings have also been reported in breast cancer, where tumor resistance arises from HER2 gene mutation (179). Therefore, therapeutic regimens combining standard treatment options (e.g., chemotherapy) with gene-editing technologies may address disease recurrence or treatment failure due to drug resistance (170).

CRISPR-Cas9 can be used to restore the function of various tumor suppressor genes (e.g., TP53, PTEN, BRCA). Upon reaching the target DNA site, Cas9 cleaves and forms specific double-strand breaks, which activate cellular repair mechanisms and subsequently repair the genome via NHEJ (Non-Homologous End Joining) or HRR (Homologous Recombination Repair) pathways15. Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog (PTEN) is an essential, multifunctional tumor suppressor gene that suppresses various cellular processes by antagonizing the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway. The loss of its activity is associated with the development of many malignant tumors and the emergence of drug resistance (180). Research has confirmed that the CRISPR-dCas9 system can specifically activate PTEN expression in BRAF-mutant melanoma or triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) human cell lines, thereby remarkably inhibiting relevant downstream carcinogenic signaling pathways and ultimately suppressing cell proliferation and migration (Figure 5a) (181). Despite the demonstrated potential of this therapy, comprehensive and careful evaluation of its safety and reliability is still required to establish CRISPR-based repair of tumor suppressor genes as a viable treatment strategy. Technical challenges such as the low efficiency and incidence of HDR repair, or the lower accuracy of NHEJ repair compared to HDR, remain to be addressed (182).

CRISPR-Cas12a is a common RNA-guided endonuclease. Compared with Cas9, Cas12a possesses several distinct advantages, including greater accuracy in targeted editing and the ability to perform multiplex targeting (183,184). The human epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is frequently overexpressed in tumor cells. Its dysregulation can activate carcinogenic signaling pathways, affect the cell cycle, apoptosis, and metastasis, thereby aggravating malignant phenotypic alterations (185). The therapy that delivers a single oncolytic adenovirus (Ad) intratumorally, co-expressing Cas12a and CRISPR RNA (crRNA) targeting the EGFR gene (Ad/Cas12a/crEGFR), has been proven to be specific and precise in editing the targeted EGFR gene (Figure 5a). It efficiently downregulates EGFR expression and ultimately exerts a potent anti-tumor effect by inducing cancer cell killing and inhibiting cancer cell proliferation (172,186).

Furthermore, leveraging its ability for multiplex gene targeting, Cas12a has been employed to simultaneously target and knock out three oncogenic mutant genes in colorectal cancer patients, such as TP53, the Adenomatous Polyposis Coli gene (APC), and the Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha gene (PIK3CA), thereby reducing the proliferation of cancer cells (187). Targeting and identifying synthetic lethal interactions in tumors through CRISPR-Cas12a also represents a promising therapeutic strategy. Synthetic lethality refers to a phenomenon in which the simultaneous inactivation of two genes results in cell death, whereas inactivating either alone is tolerated (188). For instance, studies have revealed that certain breast or ovarian cancer cells carrying BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations are sensitive to PARP inhibitors. The simultaneous loss of both genes can lead to cell death by suppressing DNA repair (189-191). Integrating this principle with CRISPR technology may enable the selective elimination of tumor cells without damaging normal cells, by targeting genes other than the specific gene that is absent in tumor cells (192,193).

CRISPR-Cas13a is a novel crRNA-guided, RNA-targeting Cas enzyme capable of specifically knockdown single-stranded RNA levels without altering the host genome, with significantly reduced off-target effects (62,194). In a study, researchers specifically used CRISPR-Cas13a to knock down KRAS-G12D mRNA in pancreatic cancer cells. The results showed that the expression of this mRNA was efficiently reduced, significantly restraining tumor cell growth and proliferation both in vitro and in vivo, and increasing cell apoptosis (195). Nevertheless, its practical application strategies remain to be further explored.

Figure 5. CRISPR-based precision therapy for tumors. (a) The therapeutic strategies for targeting tumor genes. (I) Using CRISPR-Cas9 to knock out targeted mutant KRAS genes. (II) The sgRNA-dCas9-VPR complex mediates PTEN activation. (III) EGFR gene knockout mediated by vectors co-expressing Cas12a and crRNA targeting the EGFR gene. (b) The therapeutic strategies for targeting the tumor microenvironment. (I) Enhancing tumor therapeutic efficacy through different CRISPR-mediated optimized CAR-T cell therapy strategies, including Cas9-targeted CAR gene integration into the TRAC locus, knockout of inhibitory genes such as PD-1, CTLA-4, and LAG-3, as well as editing allogeneic T cells. (II) Permanent blockade of the PD-L1/PD-1 pathway via the CRISPR-Cas9 system. (c) Therapeutic strategies targeting tumor angiogenesis are being explored. Inhibition of tumor growth and promotion of anti-angiogenic effects can be significantly achieved by precisely disrupting VEGF autocrine and paracrine pathways using HUNGER. Figure 5 was created by the authors using graphical components from Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com/), licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0) license.

6.2 CRISPR-Cas for Remodeling the Immune Microenvironment

The efficacy of cancer immunotherapy largely depends on the tumor microenvironment, particularly the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME), which includes tumor cells, immune cells, cytokines, and other components (196). The roles of these components are divided into anti-tumor and pro-tumor. The former primarily includes cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), natural killer cells (NK cells), macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), IFN-γ, and TNF-α, among others. In contrast, the latter primarily comprises regulatory T cells (Tregs), tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) or myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), TGF-β, IL-10, and PD-1 (197). Tumors can evade immune surveillance by constructing an immunosuppressive microenvironment. Immunotherapies targeting this mechanism aim to activate or restore the immune system's inherent tumor-suppressive function, thereby remodeling the immune microenvironment and improving the efficacy of anti-tumor treatment. CRISPR-Cas technology is a vital tool in immunotherapy, exerting therapeutic effects by enhancing anti-tumor immune responses or weakening pro-tumor responses (198). Strategies of CRISPR-Cas in therapies aimed at enhancing immune responses include modifying immune cells such as T cells and NK cells leveraging targeted gene-editing capabilities to improve their therapeutic efficacy, deleting genes that negatively regulate the immune system such as immune checkpoints to enhance immune activity, and precisely inserting beneficial genes such as cytokines or other immune mediators to strengthen immune responses to specific antigens (199).

With its capabilities for targeted delivery, gene editing, precision, and high efficiency, CRISPR-Cas9 can enhance the convenience, cost-effectiveness, and safety of CAR-T cell therapy. It also serves as a key support for the development of next-generation CAR-T cells, which hold broad application prospects (200). CAR-T cell therapy is based on genetic modification, enabling autologous or allogeneic cells to efficiently express a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR), thereby allowing immune cells to target tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) specifically. This precise targeting endows CAR-T cells with powerful anti-tumor capabilities (201,202). Although CAR-T cell therapy has achieved significant success in treating hematological tumors, its efficacy and applicability in solid tumors remain unsatisfactory, constrained by factors such as limited tumor infiltration, T-cell exhaustion, and toxicities (203,204). To overcome these limitations, CRISPR technology has been employed to engineer CAR-T cells with improved efficacy and reduced toxicity (Figure 5b). In the traditional manufacturing of CAR-T cells, transduction is typically performed by retroviral vectors carrying chimeric receptor sequences, which randomly integrate into the T-cell genome. This may lead to issues like carcinogenic transformation, unstable transgene expression, and transcriptional silencing. CRISPR-Cas9, however, enables delivery of the DNA cassette encoding CAR to specific genomic loci, enabling site-specific knock-in of CAR at target sites. For example, integrating CD19 CAR into the TRAC locus of T cells can result in more uniform and stable CAR expression, thereby increasing therapeutic efficacy (205). Additionally, using CRISPR-Cas9 to knock out inhibitory genes such as PD-1, CTLA-4, and LAG-3 on T cells has been certified to reverse T-cell exhaustion and enhance anti-tumor functions (206).